Printed in the Fall 2019 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard ,"Atlantis Then and Now" Quest 107:4, pg 22-26

By Richard Smoley

To this day Atlantis haunts the psyche of humankind. A half-forgotten continent that sank overnight into the ocean, reputed to have been the secret source of civilizations as far-flung as those of Egypt and Central America, it is believed to have had wondrous technology, natural and supernatural, and to have attained a level of development that we have yet to match. Even though no one has ever found any unassailable material evidence of this civilization, there are few ideas that reappear as often in occult literature.

To this day Atlantis haunts the psyche of humankind. A half-forgotten continent that sank overnight into the ocean, reputed to have been the secret source of civilizations as far-flung as those of Egypt and Central America, it is believed to have had wondrous technology, natural and supernatural, and to have attained a level of development that we have yet to match. Even though no one has ever found any unassailable material evidence of this civilization, there are few ideas that reappear as often in occult literature.

Skeptics continue to jeer at the notion of a lost continent, but such a thing does not seem as unbelievable as it may once have—certainly not, for example, to the inhabitants of Male, the island capital of the Republic of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, threatened with submersion as global warming continues to raise sea levels. Once we admit this possibility, we may find ourselves asking whether the fall of Atlantis could be repeated with our own civilization, vexed with fears of ecodisaster.

The legend of Atlantis first appears in two dialogues by the Greek philosopher Plato (c.428–348 BCE)—the Timaeus and the Critias. These texts have been cornerstones of the Western esoteric tradition for millennia, and not entirely because of their discussion of Atlantis: the Timaeus in particular describes a cosmology that would leave its impact on mystical traditions ranging from Gnosticism and Hermeticism to the Kabbalah. But it is the story of Atlantis that has most captured the public imagination.

Many of Plato’s dialogues contain myths. They are not the traditional myths of Greek religion but compositions of his own. One of the most famous examples is found at the end of The Republic. It describes a near-death experience of a soldier named Er, who goes to the realm of Hades and returns, telling of the Homeric heroes who drew lots for the lives they would lead in the next incarnation. While Plato no doubt believed in reincarnation, this story has obviously been made up to fit its setting. Many scholars regard the tale of Atlantis as a myth in this sense, even though Critias, the narrator of this account, insists that it is “a tale, which, though strange, is certainly true, having been attested by Solon, who was the wisest of the seven sages” (Timaeus 20d-e).

The real Critias was Plato’s uncle. His name had an unsavory tinge in the Athens of Plato’s day. After the city lost the Peloponnesian War to Sparta in 404 BCE, Critias was installed as one of the Thirty Tyrants, a bloodthirsty junta that ruled for a year or so before being ousted. Nonetheless, his testimony in this dialogue has a ring of truth, because Solon—a lawmaker and poet who lived c.600 BCE and who, as we have seen, was renowned for his wisdom—was a relative of one of Critias’s ancestors. Since Plato belonged to the same clan, the story of Atlantis could have been a family tradition that Plato knew firsthand.

Critias’s story, which in fact revolves around Athens, is placed 9000 years before Solon’s time—that is, around 9600 BCE. We learn that Solon in turn heard it from an Egyptian priest, who told him, “There have been, and there will be again, many destructions of mankind arising out of many causes; the greatest have been brought about by fire and water.” The priest adds, “You remember a single deluge only”—the Greeks had a legend of a flood like the one in the Bible—“but there were many previous ones” (Timaeus 22c, 23b).

Before this flood, the priest goes on to say, there was an enormous island called Atlantis, “situated in front of the straits which are by you called the Pillars of Heracles [the Straits of Gibraltar]. The island was larger than Libya* and Asia put together, and was the way to other islands, and from these you might pass to the whole of the opposite continent which surrounded the true ocean” (Timaeus 25e).

*The ancient Greeks sometimes referred to the continent of Africa as “Libya.”

The empire of Atlantis “had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia [Italy],” and was moving to subjugate Egypt and Greece as well. It was then, according to the Egyptian priest, that Athens resisted the Atlantean invaders. “After having undergone the very extremity of danger, she defeated and triumphed over the invaders, and preserved from slavery those who were not yet subjugated, and generously liberated all the rest of us who dwell within the Pillars. But afterward there occurred violent earthquakes and floods, and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way, and this was caused by the subsidence of the island” (Timaeus 25c-d). The same inundation swept Greece as well, stripping its soil and leaving it comparatively barren, as it was in Plato’s time and still is today.

How literally did Plato mean his readers to take this myth? Like nearly all of his surviving work, the Timaeus is in the form of a dialogue, a genre that allows the author to stand back from the assertions in it: they are not necessarily Plato’s claims but those of his characters. Nevertheless, Crantor, the earliest commentator on the Timaeus, writing around 300 BCE, accepted it as genuine history, as did the ancient authorities Strabo and Posidonius.

| |

|

|

| |

|

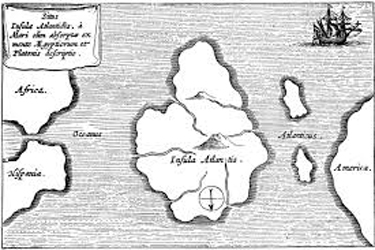

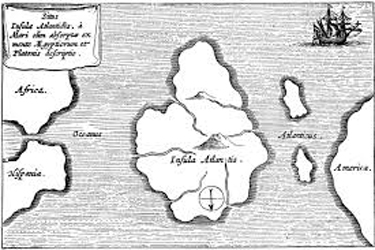

A map of Atlantis from Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus (1:82), 1664–65. The legend at the top left reads: “The location of Atlantis, an island long ago submerged into the ocean, according to Egyptian thought, and Plato’s description.” In this map, south is at the top, putting America on the right and Europe on the left. |

Plato’s date of 9600 BCE is intriguingly close to the end of the last glacial period on earth—around 10,000 BCE—at which time some land that was above water was submerged (e.g., the continental shelf that had formed a land bridge between Britain and mainland Europe), so the disappearance of the fabled land fits reasonably well into conventional scientific chronology. Nonetheless, it is still necessary to find a plausible site for the lost continent. For some bizarre reason, the most popular choice has been Thera (present-day Santorini), an island in the Mediterranean, much of whose land mass was destroyed in a cataclysmic eruption of a volcano sometime between 1650 and 1500 BCE. But since Thera does not match Plato’s Atlantis in location or size (Thera is much smaller) and since the date of the eruption is nowhere near Plato’s estimate, it is an unlikely site for the doomed civilization.

The most plausible candidate for Atlantis is an obscure geological formation known as the Horseshoe Seamount Chain, located in the Atlantic about 600 kilometers west of Gibraltar. This is a series of nine inactive volcanoes, which rise from an abyssal plain of 4000–4800 meters deep. The highest, the Ampère Seamount, nearly reaches the sea surface. Thus in the last Ice Age, it could conceivably have been above sea level. This area in the Atlantic is a meeting place for three major oceanic flow systems, making its currents unusually disturbed (Hatzsky). The horseshoe shape of the formation also evokes Plato’s description of Atlantis, whose inhabitants “bridged the rings of sea round their original home” (Critias, 115c).

After Atlantis sank, according to Plato, the area beyond Gibraltar was impossible to navigate because of the mud shoals. Aristotle also mentions “shallows owing to the mud” in this area (Aristotle, Meteorologica 354a; Barnes 1:576), and another ancient source, Scylax of Caryanda, mentions a sea of thick mud just beyond the Pillars of Hercules. The now-defunct website “Return to Atlantis” observes, “It seems that even as recently as 2300 years ago—which on the geological scale is barely an eye-blink—the Ocean beyond Gibraltar was unnavigable because of deposits of mud from a vanished island. Even today an examination of the sea bed at this point reveals an exceptionally high level of sedimentation.”

The only difference between this site and Plato’s Atlantis is that the latter was a continent larger than Asia and Africa put together. While this is hard to believe, there is nevertheless the striking fact that Plato also says that Atlantis “was the way to other islands, and from these you might pass to the whole of the opposite continent which surrounded the true ocean, for this sea which is within the Straits of Heracles [i.e., the Mediterranean] is only a harbor, having a narrow entrance, but that other is a real sea, and the land surrounding it on every side may be most truly called a boundless continent” (Timaeus 25a).

This remarkable passage suggests that—contrary to the usual beliefs—the ancients knew that there was a continent across the Atlantic, to which Atlantis once served as a gateway. Although the Americas do not surround the Atlantic, they can, from an ancient point of view, be termed “a boundless continent.” That there was a memory of a continent across the Atlantic is one of the most striking details suggesting that this account is not just fantasy.

Whether the Horseshoe Seamount Chain was really the site of Atlantis is a question for geologists and archaeologists, but even in the case of this supposedly magnificent civilization, the absence of evidence is not as conclusive as one might think. The Greek historian Thucydides (c.460–c.400 BCE), the first man in history to think about archaeology, observes about Sparta (also called Lacedaemon):

If the city of the Lacedaemonians should be deserted, and nothing left but its temples and the foundations of other buildings, posterity would, I think, after a long lapse of time, be very loath to believe that their power was as great as their renown. (And yet they occupy two-fifths of the Pelopponesesus and have the hegemony of the whole, as well of their many allies outside; but still, as Sparta is not compactly built as a city and has not provided itself with costly temples and other edifices, its power would appear less than it is.) (Thucydides 1.10; Smith, 19)

Atlantis too could have been a great and comparatively advanced civilization that left few or no material remains.

The legend of Atlantis was itself submerged in the West from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries CE, when Plato’s works were almost completely unknown. As his writings surfaced during the Renaissance, Atlantis attracted increasing speculation. Although the Bible—the supreme authority at that time—did not mention the vanished continent, it did speak of a great deluge, and on the face of it there was no reason this flood could not have engulfed Atlantis. Over the last 500 years, the theories about the lost continent have been many and manifold, ranging from the plausible to the crazy. It is not possible to go into all, or even many, of them here. Readers might want to look at Joscelyn Godwin’s book Atlantis and the Cycles of Time, which explores these views in depth.

One of the most important figures in comparatively recent times to talk about Atlantis was H. P. Blavatsky, who discussed it in her compendious works Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine. But Blavatsky’s Atlantis is not the same as Plato’s. Her intricate esoteric theory posited a number of Root Races that had preceded our own “Aryan” race. The Aryan race, in her view, was not limited to the Germanic or even to the Indo-European peoples but to practically the whole of humanity that has lived for the past million years. This Aryan Root Race was preceded by four others, two of which, the Chhaya (sic) and the Hyperborean, scarcely even made themselves manifest on the physical plane. The third and the fourth were Lemuria (named after another sunken continent that some nineteenth-century paleontologists believed to have been situated in the Indian Ocean) and Atlantis. Blavatsky wrote, “Up to this point of evolution [i.e., Atlantis, the fourth Root Race] man belongs more to metaphysical than physical nature. It is only after the so-called Fall that the races began to develop rapidly into a human shape,” although, she adds, they were “much larger in size than we are now” (Blavatsky, 2:227).

The denizens of Atlantis had a fatal flaw, Blavatsky claimed. They were “marked with a character of Sorcery . . .The Atlanteans of the later period were renowned for their magic powers and wickedness, their ambition and defiance of the gods” (Blavatsky, 2:286, 762). This fatal flaw led to their destruction by water.

So far Blavatsky’s account appears to correspond with Plato’s, at least apart from the sorcery. But the time frame she gives for the rise and fall of Atlantis extends much further back than his. Indeed “the first Great flood . . . submerged the last portions of Atlantis, 850,000 years ago” (Blavatksy, 2:332; emphasis Blavatsky’s). The inhabitants of Plato’s Atlantis were merely the last remnant of the race, the Atlanteans’ “degenerate descendants” (Blavatksy, 2:429).

Blavatsky’s account has influenced many subsequent pictures of Atlantis, particularly with its assertion that Atlantis perished because its inhabitants misused occult powers. The American “sleeping prophet,” Edgar Cayce (1877–1945) held a similar and highly influential view. His trance readings drew a picture of Atlantis that in many ways resembled Blavatsky’s, although his chronology was different and much more recent: he claimed that Atlantis was destroyed in three cataclysms in 58,000, 20,000, and 10,000 BCE. Like Blavatsky, Cayce said that Atlantis sank because its inhabitants abused their powers. Although of a spiritually higher caliber than those of the preceding Root Races, the Atlanteans mated with them, producing monstrous hybrids. The good Atlanteans, “Children of the Law of One,” wanted to help the hybrids and elevate them to their rightful position as children of God, but another faction, the “Sons of Belial,” treated the hybrids as objects for sensual gratification.

The first destruction of Atlantis, said Cayce, was due to a misuse of advanced technology for eliminating large carnivorous mammals that were overrunning the earth; the second, to a misuse of a “firestone” that gathered cosmic energy; the third, to a similar misuse of a crystal that employed both solar and geothermal power. This last destruction was complete by 9500 BCE—a date very close to Plato’s.

In a 1926 reading, Cayce mentioned the site of what he said had been the highest peaks in Atlantis—a pair of islands called Bimini, forty-five miles off the coast of Florida. For Cayce, it was (in his convoluted phrasing) “the highest portion left above the waves of a once great continent, upon which the civilization as now exists in the world’s history [could] find much of that as would be used as a means for attaining that civilization [Atlantis]” (Carter, 117. Bracketed materials are in the original).

Cayce also predicted major “earth changes”—a term that would resurface frequently in New Age circles—for the twentieth century. As he put it in 1940, “Poseidia (Atlantis) to rise again.” (Poseidia was Cayce’s name for the largest Atlantean island.) “Expect it in ’68 and ’69. Not so far away!” (Carter, 52).

Indeed Cayce predicted titanic upheavals of land and sea between 1932 and 1998. These would begin, he claimed, “when there is the first breaking up of some conditions in the South Sea [i.e., the South Pacific] . . . and . . . the sinking or rising of that which is almost opposite, or in the Mediterranean, and the Aetna (Etna) area.” But the changes would be felt all over the world. “The greater portion of Japan must go into the sea . . .The upper portion of Europe will be changed as in the twinkling of an eye.” In America, “all over the country many physical changes of a minor or greater degree . . . Portions of the now east coast of New York, or New York City itself, will in the main disappear . . . The waters of the Great Lakes will empty into the Gulf of Mexico” (Carter, 52).

The earth changes Cayce forecast for the last two-thirds of the twentieth century did not happen within his timetable, but it is becoming hard to laugh them off. Climate change today is not a possibility but a fact. To take only a couple of recent examples, the British newspaper The Guardian writes, “Alaska is trapped in a kind of hot feedback loop, as the arctic is heating up much faster than the rest of the planet. Ocean surface temperatures upwards of 10F hotter than average have helped to warm up the state’s coasts” (Cagle). As for the other pole, The Guardian also reports, “The plunge in the average annual extent means Antarctica lost as much sea ice in [the past] four years as the Arctic lost in 34 years” (Carrington). The rapid melting of the ice caps may (among other things) raise the oceans’ levels, flooding coastal areas such as the East Coast, as Cayce predicted. He may have been right about the events if not about the timing.

Furthermore, the theory of plate tectonics—which show that the continents drift around the crust of the earth over a period spanning geological ages—makes the idea of rising and falling continents somewhat more plausible than it was a hundred years ago (although on a much larger time scale than Plato allows). In any case, the idea of a flooded continent does not seem quite as foolish as it once did.

Concerns about a repetition of the fall of Atlantis are fed by another long-standing Western nightmare: the fear that the fall of the Roman Empire will happen again. This anxiety surfaces in curious places. A 1960 feature from Mad magazine tells us that “America is getting soft,” to the point where our legs will dwindle down to vestigial features, making us easy targets for “the lean, hungry barbarians from the East.” The accompanying cartoon shows a fat, blank-faced American being pushed over like a round-bottomed doll by a gaunt and bucktoothed Red Chinese soldier.

To turn to high culture, Edward Gibbon, whose eighteenth-century account of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire still remains the definitive version today, felt obliged to interrupt his history to prove that the fall of Rome could not happen again, partly because Western civilization had been transplanted to the Americas. “Should the victorious Barbarians carry slavery and desolation as far as the Atlantic Ocean,” Gibbon wrote, “ten thousand vessels would transport beyond their pursuit the remains of civilized society; and Europe would revive and flourish in the American world which is already filled with her colonies and institutions” (Gibbon, ch. 38). He would not have mentioned this fear, or felt the need to refute it, unless it was vivid in the minds of his eighteenth-century readers.

Still another layer of this collective fear lies in the dread of apocalypse inspired by biblical books such as Daniel and Revelation. Anxieties about the demise of our civilization thus go back as far as Western civilization itself. Today, taking on a multicultural form, they have fastened onto notions of an end of time taken from native cultures (such as the 2012 sensation) and, in a secular context, to ecodisasters of one sort or another. Indeed one senses that certain interest groups foster this anxiety on the grounds that people will otherwise sit around in complacency.

I personally do not agree with this tactic. We have lived long enough with apocalypse, and we do not need updates of it to motivate us. People do not make the best decisions in moods of anxiety and panic. If we are to solve the problems that confront us, it will be by facing them soberly and realistically, without feeling the need to terrify ourselves into action.

To conclude with a prophecy of my own for the New Age: in the New Age we will have to live without prophecies.

This article previously appeared in New Dawn magazine and in Richard Smoley, Supernatural: Writings on an Unknown History (Tarcher/Penguin, 2013). Richard’s latest book, A Theology of Love () is reviewed in Quest, fall 2019.

Sources

“Atlantis,” Wikipedia; <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantis>; accessed June 27, 2019.

Barnes, Jonathan, ed. The Complete Works of Aristotle. 2 vols. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton/Bollingen, 1995.

Berg, Dave. “America Is Getting Soft,” Mad 54 (April 1960), 25.

Blavatsky, H.P. The Secret Doctrine. 2 vols. Wheaton: Quest, 1993 (1888).

Cagle, Susie. “Baked Alaska: Record Heat Fuels Wildfires and Sparks Personal Fireworks Ban,” The Guardian (website), July 3, 2019.

Carrington, Damian. “’Precipitous Fall in Antarctic Sea Ice since 2014 Revealed,” The Guardian (website), July 1, 2019.

Carter, Mary Ellen. Edgar Cayce on Prophecy. New York: Paperback Library, 1968.

Hamilton, Edith, and Huntington Cairns, eds. Plato: The Collected Dialogues. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton/Bollingen, 1961

Hatzky, Jörn. “Physiography of the Ampère Seamount in the Horseshoe Seamount Chain off Gibraltar,” Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven (2005); http://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.341125; accessed June 27, 2019.

Hornblower, Simon, and Anthony Spawforth, eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3d ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Return to Atlantis (website), http://www.returntoatlantis.com/retc/gradual.html; accessed Jan. 12, 2011.

Smith, Charles Forster, ed. and trans. Thucydides, vol. 1. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930.

This is an issue on ancient civilizations, but I hope you will indulge me if I talk about our present one.

This is an issue on ancient civilizations, but I hope you will indulge me if I talk about our present one.

The Theosophical Society of Wichita, Kansas, became a certified study center in February 2018. It is not easy to start a new study group in America’s Bible Belt, and developing a core group of committed students to study Theosophy is an even greater task. But I am happy to report that we have a dedicated, enthusiastic study group and we are learning from each other at every meeting.

The Theosophical Society of Wichita, Kansas, became a certified study center in February 2018. It is not easy to start a new study group in America’s Bible Belt, and developing a core group of committed students to study Theosophy is an even greater task. But I am happy to report that we have a dedicated, enthusiastic study group and we are learning from each other at every meeting.

What comes to your mind when you think of ancient civilizations? Some of us might think about ancient Greece or Rome, Crete and the Minoan civilization, Mesopotamia, or even Atlantis and Lemuria. Others might even wonder about the connection between ancient civilizations and aliens. One thing is certain: the concept of ancient civilizations gives us the opportunity to peer into antiquity, imagine what it must have been like, and contemplate what we can learn from the ancient past.

What comes to your mind when you think of ancient civilizations? Some of us might think about ancient Greece or Rome, Crete and the Minoan civilization, Mesopotamia, or even Atlantis and Lemuria. Others might even wonder about the connection between ancient civilizations and aliens. One thing is certain: the concept of ancient civilizations gives us the opportunity to peer into antiquity, imagine what it must have been like, and contemplate what we can learn from the ancient past. Words are magic. Thoughts create actions that manifest forms. No matter what language you use—English, Spanish, Sanskrit, Chinese, or hieroglyphs—thoughts are things, but especially in those languages that combine image, sound, and meaning (intention). Ancient Egyptians knew this to be true. They called their sacred hieroglyphs medju neter (the language of god), and the power of that language they called heka (magic).

Words are magic. Thoughts create actions that manifest forms. No matter what language you use—English, Spanish, Sanskrit, Chinese, or hieroglyphs—thoughts are things, but especially in those languages that combine image, sound, and meaning (intention). Ancient Egyptians knew this to be true. They called their sacred hieroglyphs medju neter (the language of god), and the power of that language they called heka (magic).