Urban Mystic: Reminiscences of Goswami Kriyananda

Printed in the Fall 2019 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Grasse, Ray ,"Urban Mystic: Reminiscences of Goswami Kriyananda" Quest 107:4, pg 27-31

By Ray Grasse

Your everyday life is your spiritual life.

—Goswami Kriyananda

In the months leading up to my twentieth birthday, I wrestled mightily with the notion of linking up with a spiritual teacher. It became somewhat fashionable in those days to seek out a guru after the Beatles, Donovan, and the Beach Boys traveled to India and had done just that. More than a few writers at the time went so far as to assert that if you entertained any hope of finding “enlightenment,” you’d better align yourself with a spiritual teacher—or you might as well just forget about it.

But the thought of putting myself at the feet of a guru troubled me, for any number of reasons. One of those involved a certain fear of commitment, since I thought that discipleship meant aligning yourself with a teacher for eternity. What if you picked the wrong one? But I also worried about sacrificing my individuality, since I (mistakenly) feared that was part and parcel of the process. Besides, didn’t the Buddha attain enlightenment on his own?

Formal discipleship or not, I knew I wanted to acquire some of the knowledge offered by these teachers should the chance ever arise.

As it turned out, that chance did arise. During sophomore year in college, a fellow student told me about an American-born swami in the area who was supposedly knowledgeable in the ways of mysticism and meditation. He called his center the Temple of Kriya Yoga, and it was located then on the fifth floor of an office building on State Street in downtown Chicago. Despite my nervousness about entering this new environment—I was fairly agoraphobic at the time, so social gatherings were a source of anxiety for me—I finally attended one of his lectures to see for myself what this man had to offer.

I was nineteen at the time, and felt very out of place sitting there amongst those strangers, some of whose behaviors and appearances were very different from mine. I had no problem with the long hair or the flowing dresses, but I was a bit wary of the bearded men with beads around their necks who brandished inscrutable smiles. Did that look imply peace of mind, or rather a cultlike mindlessness?

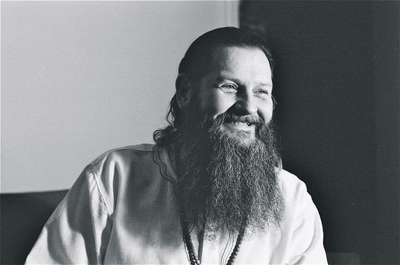

Kriyananda—or as the others referred to him, Goswami Kriyananda—certainly looked the part of a guru, with his long beard and flowing hair.* He spoke that first night for a little over an hour, and his knowledge of mystical subjects was impressive. So impressive, in fact, that before I knew it, I’d attended his classes and lectures for nearly fifteen years in all.

Kriyananda—or as the others referred to him, Goswami Kriyananda—certainly looked the part of a guru, with his long beard and flowing hair.* He spoke that first night for a little over an hour, and his knowledge of mystical subjects was impressive. So impressive, in fact, that before I knew it, I’d attended his classes and lectures for nearly fifteen years in all.

Over the course of those years I became marginally involved with the temple itself, volunteering my time to help design logos or advertisements, joining one or another committee to help plan events, and on a handful of occasions teaching classes. Yet unlike most of the others, I was never compelled to take the final plunge and become a formal disciple. That proved to be a double-edged sword, for reasons that should become clearer as my story moves along.

It wasn’t long before I learned his original name was Melvin Higgins. He was born in 1928, and up to then had lived most of his life in Chicagoland. (As for why he never relocated elsewhere, he once remarked, “I believe one should bloom where one is planted.”) He graduated from college, worked in the business world for a while, and acquired a following of students that expanded in size as his center changed locations around the city. He first taught out of his home in Hyde Park, on Chicago’s south side, after which he moved to several locations in the downtown Chicago area, finally relocating the temple in 1979 to the Logan Square neighborhood on the city’s north side.

Kriyananda was notably unpretentious, and drove an old car at a time when some other better-known teachers were flaunting their conspicuous wealth in the form of multiple Rolls-Royces and phalanxes of fawning attendants. He also made himself surprisingly accessible to students after lectures, which wasn’t a common practice among teachers of his caliber. It was relatively easy to walk into his office and approach him with pressing concerns; in fact, there was almost always a line of students outside his office, looking for answers to their questions or for emotional support.

Despite that ease of access, it took me almost a full year to build up the nerve to go in and speak with him one-on-one, because I was initially intimidated by his presence. When I finally did approach him, however, he couldn’t have been friendlier. Over those next few years we wound up carrying our conversations outside the temple, enjoying talks over lunch or dinner while running errands in the city together, or talking on the phone.

Indeed, the fact that I wasn’t a disciple seemed to make it easier for him to be relatively open with me, since he wasn’t as obliged to play the formal role of teacher with me and maintain the disciplinary posture that often entails. He was always down-to-earth in our exchanges, never pious or ethereal, and it wasn’t unusual for him to spruce up our conversations with a well-chosen expletive now and then. He was definitely a Chicago-born teacher, no doubt about it—and that was all for the better, as far as I was concerned.

Every chance I had to speak with him over the years, I soaked up as much information as I could about subjects like karma, mythology, ancient history, astrology, meditation, comparative religion, or even politics. And he never held back, no matter how persistent or annoying I could be (and I could be pretty persistent and annoying). I was especially impressed by his openness about his own imperfections. It was obvious he didn’t want to appear better than anyone else. Like his own guru, Shelly Trimmer, he didn’t wear his spirituality on his sleeve.

But I also suspect that low-key style may have affected his popularity and fame as a teacher. That’s because some of the more well-known spiritual teachers making the rounds at the time projected a carefully cultivated air of “holiness” and solemn unapproachability that many interpreted as signs of spiritual merit—whether they actually possessed any or not. This wasn’t Kriyananda’s style at all. He could be self-effacing, often humorous, and very human. Yet underlying that humanness was a spiritual depth and core integrity that was obvious to me. On countless occasions, for example, I watched as he went out of his way to help others, sometimes at considerable expense or inconvenience to himself. At bottom, he struck me as a profoundly sensitive soul with a deep compassion for others.

I suspect some of that sensitivity may have come from experiencing a hard life while he was growing up. Before he was five, his father died, and his mother remarried a man who ushered several more children into an already large household, with young Melvin now having to shoulder much of the responsibility of helping to raise those younger siblings. He openly admitted to being so shy when younger that he could hardly speak in social settings, something which undoubtedly pained him greatly. I had the sense that his way of coping back then was escaping into books and learning as much as he could about spirituality, science, and history.

Over the years I interacted with him, Kriyananda displayed a work ethic that confounded me with its sheer energy. He gave formal lectures at least twice a week, on Sunday afternoons and Wednesday evenings, in addition to continually offering courses which extended anywhere from six weeks to twelve months, along with rigorous programs specifically designed for disciples and aspiring swamis. All of that was on top of an astrological practice that had him seeing clients five or six days a week, while he also churned out a series of books and pamphlets. I never quite figured out how he managed to do it all, and suspected he must have gotten by on just a few hours of sleep every night.

What kept him going? Though I knew he was passionate about teaching, I also knew the entire process wasn’t always a stroll in the park. In particular, keeping the temple afloat was an expensive endeavor and generated a mountain of bills—and he was the one mainly responsible for paying them. He once told how exciting it was when he first opened the temple, but then how challenging it became after a few years, not just financially but in overseeing the parade of personalities that streamed through it. When he mentioned this to his own guru, the elder teacher responded, “Kriyananda, it’s very easy to create something, whether that be a marriage, a business, or a temple. But it’s much harder to sustain that creation.” But sustain it he did, in the process affecting the lives of many thousands of men and women, both directly and indirectly.

The Teachings

Kriyananda lectured on a wide range of esoteric and spiritual topics, but had a particular genius when it came to astrology. He was a virtual encyclopedia of information on both Eastern and Western astrological systems, and often discussed interpretive techniques I’d never heard of before, and to this day I’m still unsure where he learned them. Just as impressive was his hands-on talent for reading horoscopes. Much of the time Kriyananda seemed to have nearly X-ray vision for deciphering birth charts and what they revealed about their owners. I know of instances where he said things to individuals that were accurate in detailed ways that continue to baffle me, since I could find nothing in those horoscopes which prompted those insights.

Yet the central core of his teachings revolved principally around Kriya Yoga, a holistic tradition known for consciousness-raising techniques and a comparatively “householder” approach toward spiritual practice. With the notable exception of Paramahansa Yogananda, famed author of Autobiography of a Yogi, most of the teachers in this branch of the Kriya lineage were married and held regular jobs while teaching students. That was a definite plus as far as I was concerned, since I certainly wasn’t interested in celibacy.

Kriyananda—or Melvin, as he was known early in life—first encountered the teachings of Kriya Yoga up close and personal through a mysterious teacher in Minnesota named Shelly Trimmer, whom I’d eventually encounter myself (and whom I wrote about in my book An Infinity of Gods, excerpted in Quest, fall 2017).

With both his sun and moon in Taurus, there was a notable practicality to Kriyananda’s teachings that was somewhat less pronounced in Shelly’s sometimes more “cosmic” perspective. Kriyananda had a talent for distilling complex spiritual doctrines into simple terms, such as this gem: “Everyone is trying to find God when they haven’t even found their humanness yet.” In that respect he shared a close affinity with the here-and-now emphasis of Zen Buddhism (he once even remarked that Paul Reps’ book Zen Flesh, Zen Bones was “one of the greatest books ever written”).

That subtle difference between his spiritual perspective and Shelly’s was apparent in a comment he once made about something the older guru said to him. On one occasion Shelly remarked how he never felt entirely comfortable in his physical body. “Other people are trying to get out of their physical body, but I have trouble staying in mine,” Shelly said laughingly. In contrast with that perspective, Kriyananda took a more Zenlike approach when he said, “That’s one of the few areas where I respectfully disagree with my guru. I believe that we should be comfortable wherever we find ourselves, whether that be in a twenty-room mansion or a tiny shack.”

There were a few other ways in which Kriyananda and Shelly differed in their approach toward teaching. For instance, Shelly had a pronounced trickster streak and was known to pull the wool over students’ eyes—a teaching tactic of which Kriyananda found himself on the receiving end more than once. Directly as a result of those sometimes frustrating lessons, he consciously chose to go in a different direction with students, once saying to me, “Ask me a question, and I’ll shoot straight from the hip; I’ll give you a direct answer.”

Another key difference between them concerned the matter of legacy. Shelly’s modesty about his own contribution to the world was such that he felt no pressing desire to write books or preserve his ideas for posterity, other than teaching in that distinctly low-key, one-on-one fashion of his. Shelly genuinely seemed to believe that in the greater scheme of things, his words ultimately meant very little. “If I don’t do it or say it, someone else undoubtedly will,” he once remarked.

In contrast with that proverbial view from 30,000 feet, Kriyananda had a more practical, boots-on-the-ground attitude. Early on, he set about working to preserve his ideas not only in books but through creating a library of audiotapes and videos that could be accessed online and would survive long after he had passed.

Which of those two perspectives is the right one, Kriyananda’s or Shelly’s? To my mind, both are. They were simply different approaches, each with its own validity and value. Kriyananda and Shelly viewed the world through different lenses, set to very different magnifying powers, and I drew enormous value from both of them.

Kriyananda the Mystic

Of the varied insights I gathered from Kriyananda over the years, I especially valued those of a more personal nature, when he related experiences he had as an early student or later on as a teacher. Indeed, of all the teachings I’ve heard delivered by various teachers over the years, the ones that stand out most vividly in my memory are those of a more personal nature, even more than their philosophical ruminations. That was true with Kriyananda too. As just one example, I recall a series of lectures Kriyananda delivered on Taoist philosophy sometime during the late 1970s, yet to this day the only thing I remember from that six-week course was a personal anecdote he shared in passing about a conversation he had with his own teacher, and which remains as vivid to me now as the day I heard it.

Most of these personal anecdotes were of a spiritual nature, describing some struggle or lesson he learned while growing up, or during some encounter with his guru. But a few of the more intriguing tales involved anecdotes of a psychic or paranormal nature. Why did those interest me? Because they suggested there was more going on with the man than meets the eye.

Kriyananda strongly discouraged students from becoming overly concerned with psychic abilities or magical powers. Indeed it was one reason he never recommended Yogananda’s famed Autobiography of a Yogi to new students: he felt its emphasis on exotic powers and experiences misrepresented the spiritual path in certain respects. Yet he never denied that those abilities existed, and on rare occasions spoke about his own paranormal experiences. While it’s impossible for me to judge the ultimate validity of these accounts, I never sensed the slightest hint of ego or dishonesty in their telling—and as I’ll explain shortly, I had reasons of my own to believe they were more than just fabrications.

Many of those stories were brief and simple, and casually mentioned in the course of longer lectures or conversations. One simple example was the time he spoke about driving along the city’s outer drive that morning and seeing a dead dog lying alongside the road. He described perceiving the spirit of the dog wandering around the accident scene, looking dazed and confused about what had happened to it. Feeling compassionate for the dog, he stopped his car along the shoulder of the busy road to tend to it, blessing it and sending it on its way.

Or the time he was drafted into the army during the Korean War, where he served as a medic and found himself situated near the battlefront. While huddling in the trench during one conflict, he described seeing a fellow soldier rise up and march towards enemy lines, only to be shot and instantly killed. But while the soldier’s body dropped to the ground, Kriyananda said he saw the man’s astral double keep marching forward, as though he hadn’t realized he’d been shot.

Once he spoke of attending a Catholic service that was being conducted by a priest with whom he’d been friends. Normally, he explained, he would sit in the back of a church and see the energies of the parishioners during the service; whenever the priest would lift the chalice upwards at that point of communion, he’d see the spinal currents of everyone rise upwards as well, as if in sympathetic resonance with the ritual up on the altar.

But on this particular Sunday morning, the priest lifted the chalice upwards—and nothing happened in the spines of the parishioners; no subtle energies were stirred. After the service, he spoke to his priest friend and inquired whether there was anything different about the ceremony this particular Sunday. It turned out the church had run out of wine, so the priest substituted grape juice instead that day. Kriyananda used this story to illustrate the importance of symbolic “purity” in rituals and the need to use the appropriate ingredients to embody one’s intentions.

Then there was this. One afternoon in 1978 Kriyananda emerged from his office to deliver his usual Sunday afternoon talk, but he was looking noticeably disturbed about something. Sitting down before the podium, he shook his head back and forth gently a few times and muttered softly, “They’re doing some crazy things down there”—with no further explanation. He continued on with his talk, leaving myself and the others in attendance perplexed about that opening comment. What did he mean by “down there”? Or by “crazy things”? I continued wondering about it, so after his talk I headed downstairs to the lower floors of the hotel lobby to see if he might have been referring to something taking place there, or even outside the building. But I found nothing unusual at all.

Later that evening, I turned on the TV to hear reporters talk about news trickling in from South America about a mass suicide down in Guyana. Over the next few days, reports revealed that over 900 residents of Jonestown had taken their lives under the direction of cult leader Jim Jones—and it had all started unfolding around the time of Kriyananda’s talk. Was he psychically sensing the mass tragedy happening far away? There’s no way to know for sure, but that was the only time I ever heard him make a public comment like that.

There were even some possible instances of prophecy. One of them involved a young woman named Karen Phillips, a disciple of his and a good friend of mine from the suburban town I was living in, Oak Park. While lecturing privately to his disciples one day (as related to me later that week by his disciple Bill Hunt), Kriyananda made this sobering remark: “In six weeks one of you will no longer be with us.” Was he implying someone was going to move out of state? Or something more serious? Most of those in attendance that afternoon had no idea what to make of the statement, and probably just forgot about it after a few days. But I was intrigued enough on hearing about it that I carefully kept an eye on the calendar to see if any of his disciples might be departing the temple in six weeks.

Exactly six weeks later, I walked into the temple to attend a class when a phone call came in to the front desk. The receptionist picked it up, and on the other end of the line was someone saying that Karen Phillips had been brutally murdered the night before. As the receptionist broke the news to Kriyananda, he looked concerned but not surprised. Eventually, the case received worldwide media coverage because of one singularly odd element: the culprit was identified as a young Bible student living several doors down from Karen, who went to the police shortly afterwards to describe a dream in which he witnessed precise details of the murder. Because of how closely the dream matched the actual crime, he was arrested and convicted of the murder, spending several years in jail before his conviction was finally overturned on appeal.

It was the only time I heard Kriyananda ever make a prediction that dramatic, and I naturally wondered how he arrived at it. Years later, Kriyananda may have provided a clue when a local magazine interviewed him and asked how anyone could verify whether an astral projection experience was valid or just a fantasy. He answered by describing his own early experiences with astral projection, and what he learned from them:

I (eventually) encountered disembodied souls who told me about their children and what was going to happen to them. Years later, these events manifested exactly the way the parents said they would. This evidence absolutely confirmed the afterlife’s existence and its link to human earth life and earth life to the afterlife. It was those experiences that removed any remaining doubt that humans were able to see into the afterlife.

Interesting stories all, no doubt. But how could I be sure they weren’t anything more than just coincidence, or fabrications? The answer is, I can’t—not positively anyway. But in some instances the unusual phenomena I witnessed did involve me directly, in which case they took on an entirely different weight. Here are a couple of examples.

Consider the time I had a conversation with Kriyananda and posed a series of questions to him on a variety of subjects while I recorded his comments on the battery-powered tape recorder I’d placed on his desk, where it remained near to me and never within his reach. One of those questions I asked him concerned the existence of God, and he may well have given me a fascinating answer; but unfortunately I was so busy checking the next question on my sheet that I barely noticed what he was saying. When I finally looked up from my paper, there was a look on his face of mild exasperation, as though he could tell I wasn’t really paying attention and was too caught up figuring out my next query. On top of that, he shook his head slightly and muttered something to the effect that, “I really shouldn’t have said quite so much.” I wasn’t too worried, though, since I’d been recording the conversation and knew I could always listen to his answers once I’d returned home—right?

But before I left the building that day, Kriyananda did something odd. He came up to me and said, “Wait a second, Ray, can I see that tape?” “Sure,” I said, as I pulled out the cassette and handed it over. Grasping it with one hand, he proceeded to quickly rub the cassette tape two or three times with his index and middle fingers, then handed it back to me with an almost mischievous look on his face. As he turned and walked away from me, I could only wonder what that was all about.

That night at home, I excitedly sat down to listen to the tape, and was especially interested to hear that one section of the conversation where I asked him about God. But lo and behold, when I got to that part of the tape, it was blank. Exactly when I expected to hear him answer my question, there was no sound on the tape at all, only silence. Then, right at the point where I launched into my next question, the sound on the tape mysteriously started up again. That silent spot was the only blank patch on the entire recording.

I was baffled, and started to mentally retrace my steps from earlier in the day to see if there was any conceivable way he could have done something to the tape or the recorder to make that glitch occur. But the recorder was in my possession the entire time, and was running on batteries rather than via any power cord. He never once touched it. Still skeptical about what happened, the next time I walked into the Temple and saw him, I asked right off, “OK, now, how did you do that?” From the look on his face, it was obvious he knew exactly what I was referring to, but he just laughed and walked away.

Then there was this. Throughout much of that period I struggled with meditation, often feeling as though I was simply spinning my wheels in the backwaters of conventional mind. I saw others sitting quietly and motionless during their meditations, yet I usually felt frustrated by my own restlessness and inability to go very deep in my meditations. But for one short but unusually fruitful stretch of time, I seemed to strike gold with one Kriya technique known as the Hong Sau mantra. This is a silent, strictly internal mantra that is coupled with one’s breathing pattern. For that relatively brief span of time, things came together for me in a powerful way, to where I felt as though I had finally gotten what the technique was about—or at least one aspect of it (since a given technique doesn’t necessarily have a single intended outcome). Each time I engaged this technique, I experienced a heightening of awareness along with a welling up of blissful energy that was dramatic and deeply pleasurable.

During one of Kriyananda’s talks, I was sitting in the back of the dimly lit room and began practicing the Hong Sau technique. My eyes were closed, and I was completely silent, with nothing externally to indicate what I was doing internally. Then, shortly after I began feeling that surge of blissful energy in me, I heard Kriyananda stop lecturing in midsentence and go completely silent for about fifteen seconds. That wasn’t at all normal for him during a talk, so I opened my eyes to see what was going on—only to see him peering through the darkness directly at me, as everyone else in the room turned to see what he was looking at. Embarrassed by the sudden attention, with all eyes now directed at me, I stopped the technique, and Kriyananda resumed his lecture as if nothing had happened.

Exactly one week later, a friend of mine (who didn’t know I was using that technique) happened to walk into Kriyananda’s office to ask if he would teach him the Hong Sau mantra. Kriyananda replied, “Why don’t you ask Ray to teach it to you? He seems to be having some pretty good luck with it.” When my friend told me of that exchange, I was floored, not only because it indicated Kriyananda knew I was having a powerful meditation that afternoon, but even pinpointed the exact technique I was using. That was impressive, I thought.

Instances like those led me to accept the possibility he did possess unusual psychic abilities. During one conversation with him about my own inability to intuit people’s intentions, I lightheartedly said, “We can’t all be as psychic as you, Kriyananda!” To which he claimed he wasn’t born that way, and that while young, he was about as “unpsychic as anyone could be.” Being an earthy double Taurus, he added, he originally believed if one couldn’t touch, taste, or measure something, it just wasn’t real. He seemed to be implying that it was a result of extensive meditations over the years that his intuitive powers developed as far as they had.

Yet I also suspect those unusual potentials may well have been latent from birth, just waiting to be triggered. I say that for this reason. I took a course in palmistry from him at one point in the 1970s, and in one class he used his hand to make a point about the length and shape of the lines in the palm, and what these meant from a symbolic standpoint. It was then that I happened to notice something very unusual about the little finger on his right hand—the finger associated by astrologers and palmists with the mind and the planet Mercury. Instead of the usual three joints, his little finger had four. That was surprising, so I asked him whether that indicated unusual mental capacities. He laughed and humbly played it down, saying, “Yes, but remember, I’m left-handed, so the usual view that the left hand shows inborn potentials and the right hand shows what you’ve done with them is reversed in my case!” I frankly didn’t quite buy his humble revision of traditional palmistry theory, but revision or not, it was an anomalous anatomical feature I’d never seen on anyone’s hand before or since.

The Final Years

Unfortunately, despite a few peak moments here and there, my own attempts at meditation were unfolding at a snail’s pace, and more often than not I struggled with simply sitting still. The longer I studied at the temple, the more I realized how much work I still needed to do in that respect—which is when I began entertaining the possibility of taking part in a longer-term meditation retreat somewhere else. Thus in late 1986 I went off to live for several months at Zen Mountain Monastery in upstate New York, where I managed to learn a few more helpful things about meditation.

But I kept in touch with Kriyananda over the coming years, calling him on occasion or traveling into the city to meet him in his office. For me, one of the main values of having access to a spiritual teacher is the chance to get honest feedback about one’s own spiritual or psychological progress—however painful that can be at times. Had he been my actual guru, I suspect he would have taken an even stricter stance with me and offered more explicit suggestions about how to enhance my practice; and had that happened, I have no doubt I would have grown much faster and farther than I did, spiritually. But simply being able to get any of his feedback on my life and mind from time to time was immensely valuable. So just as I had always done during the years I attended talks at the temple, I would ask, “Where do you think I most need to work on myself now?” Generally, he would calmly but compassionately respond with comments like, “You lack self-discipline” (which was true); or “You’re too much in your head, Ray” (also true), or “You need to meditate more” (very true, too)—and other pointed observations.

But on some occasions, he’d extend a touching compliment out of the blue, and those were meaningful in a different way. For instance, I came to know a student of his named Rebecca Romanoff, with whom I spent much time over the years as friends. We would get together for lunch or dinner sometimes, sit along the lakefront, or go to see a movie. Eventually, many years later, some time after his first wife died from cancer, Kriyananda and Rebecca got married, and they lived together until her death in 2013.

But in 1983, a couple of years prior to their marriage, she invited Kriyananda and me over to her apartment for dinner, where we spent the evening talking about a wide variety of subjects. At one point, I began reminiscing with Rebecca about some of the activities we enjoyed doing back in the old days, at which point she interjected, very self-critically, “Oh, you must have thought I was such a basket case back then.”

I was genuinely surprised to hear how hard she was on herself—especially considering I always regarded her as the one who had it together, and that I had been the neurotic one, not her. So I quickly responded, “Oh, Becky! I’ve never judged you like that!” At which point Kriyananda chimed in unexpectedly, “You know, that’s something you and Shelly have in common; you’re the two individuals I know who aren’t at all judgmental towards others.” To be compared like that with his teacher—even in such a modest way—was deeply moving, especially coming at a time when I was dealing with a string of personal disappointments in my life.

In the summer of 2013 I received the sad news that Rebecca had passed away. Around that time I decided to preserve what I could of the teachings I’d gathered from both Kriyananda and Shelly, as I began sorting through the records of my years studying with them. In Kriyananda’s case, that involved searching through several dozen notebooks I’d compiled from which I selected key passages and quotes which I felt distilled his teachings in more digestible form. As it so happened, on April 21, 2015, virtually the same day I finished that selection and posted those quotes online, I received word that Kriyananda himself passed away, having lived out his last days in France. I’d sent him a message just two weeks earlier to get his approval on what I had compiled, just to make sure I wasn’t misrepresenting his thoughts in any way. When I didn’t hear back from him, I was perplexed, since he normally responded fairly quickly. When I received word of his passing, though, I realized he probably hadn’t been in any condition to communicate with me at that point.

* There are several teachers in the yogic tradition named Kriyananda (notably the late Swami Kriyananda of California, aka J. Donald Walters, with whom the Chicago-born Kriyananda is sometimes confused). A simple way to distinguish the two teachers is through their titles: the Kriyananda I’m profiling in this article was known by the honorific Goswami, rather than Swami.

Ray Grasse worked on the staff of Quest magazine during the 1990s. He is the author of several books, including The Waking Dream, Under a Sacred Sky, and An Infinity of Gods: Conversations with an Unconventional Mystic—The Teachings of Shelly Trimmer. This article is excerpted from his book Urban Mystic: Recollections of Goswami Kriyananda. Ray’s website is www.raygrasse.com.

The National Lodge of the Theosophical Society in America is a community formed in 1996 to provide study courses for members who are not near a lodge or study center. Since 2003, TSA national secretary David Bruce has been in charge of managing the National Lodge. Part of his task has been to write cover letters for the material that is sent.

The National Lodge of the Theosophical Society in America is a community formed in 1996 to provide study courses for members who are not near a lodge or study center. Since 2003, TSA national secretary David Bruce has been in charge of managing the National Lodge. Part of his task has been to write cover letters for the material that is sent. The model for the evolution of humanity presented by the esoteric philosophy is far more complex than the modern scientific views on the subject. In The Secret Doctrine, H.P. Blavatsky states that humanity develops through seven great evolutionary cycles, called “Root Races,” which give rise to seven consecutive human civilizations.

The model for the evolution of humanity presented by the esoteric philosophy is far more complex than the modern scientific views on the subject. In The Secret Doctrine, H.P. Blavatsky states that humanity develops through seven great evolutionary cycles, called “Root Races,” which give rise to seven consecutive human civilizations. When we consider tragedy and loss in light of the perennial wisdom, it is almost impossible to avoid a discussion regarding karma. During the production of this issue, I had a conversation with Quest editor Richard Smoley about the Theosophical perspective on karma. As is usual with Richard, his statements make one think deeply; not surprisingly, then, our conversation elicited opportunities for me to contemplate my own personal perspective.

When we consider tragedy and loss in light of the perennial wisdom, it is almost impossible to avoid a discussion regarding karma. During the production of this issue, I had a conversation with Quest editor Richard Smoley about the Theosophical perspective on karma. As is usual with Richard, his statements make one think deeply; not surprisingly, then, our conversation elicited opportunities for me to contemplate my own personal perspective.