Printed in the Summer 2020 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard, "Why Ritual Works: An Explanation Based on the Hawaiian Tradition of Huna" Quest 108:3, pg 34-36

By Richard Smoley

The way up and down are one and the same.

Heraclitus

The word ritual can evoke mysterious power: the smell of incense, the pageantry of ceremonial robes, the resonance of prayers muttered in a low singsong. But the word can also connote something dead and stultifying, actions carried out for the sake of form without any remembrance of the meaning behind them.

The word ritual can evoke mysterious power: the smell of incense, the pageantry of ceremonial robes, the resonance of prayers muttered in a low singsong. But the word can also connote something dead and stultifying, actions carried out for the sake of form without any remembrance of the meaning behind them.

Nearly everyone with any experience of ritual will, I think, attest to its dual nature. Sometimes a simple ceremony with a prayer and a bit of incense can evoke tremendous power, while a church service that has been performed millions of times over millennia will seem dull and pointless.

Why should ritual work when it works? Why does it all too rapidly decay into the lifeless and perfunctory? While many different accounts attempt to explain the nature and power of ritual, one of the most simple, elegant, and compelling is set out in the Hawaiian tradition of huna.

Huna is Hawaiian for secret, and it purports to be the teachings used for centuries by Hawaiian shamans known as kahunas—“keepers of the secret.” But perhaps the best-known version today is principally the work of Max Freedom Long (1890–1971), who lived in Hawaii for a number of years, researching its magical traditions.

To what extent Long’s teaching really reflects the wisdom of the ancient Hawaiians is open to debate. Other versions of huna, for example, Serge Kahili King’s, differ from Long’s in some major respects. (See the “Sources” section at the end of the article for other perspectives on huna.) But this article will concentrate upon Long’s system.

Long never claimed to have any direct transmission of teachings from the kahunas, since their religion was officially suppressed after the white man took control of Hawaii. Instead Long was something of an autodidact. After being exposed to a number of strange phenomena connected with the kahunas—instantaneous healings, firewalking, and curses that made their victims wither away despite the ministrations of modern medicine—he decided to look into the causes behind them. But the kahunas were not forthcoming with their knowledge, and Long met a dead end, until he got a simple idea.

Long reasoned that if there were certain magical teachings in Hawaii, there must be words for them in the Hawaiian language, and that the words must provide some clue to the teachings. So he painstakingly went through Andrews’ Hawaiian-English Dictionary and began to examine words for things like spirit to see what they might reveal. After dissecting the words into what he considered their etymological roots, he set out his findings in a number of books.

Long came up with a strikingly simple, coherent, and intelligent system. Its fundamental insight—which appears in shamanic traditions the world over—is that a human being, so far from a being a single, coherent self, is a confederation of three entities that can work in greater or lesser accord. Their interactions go far to explain certain peculiarities of human nature.

Consider, for example, inner conflict. It seems to be endemic to human nature: all but the most perfectly realized beings—and perhaps even they—are subject to it to one degree or another. If we look at the animal world, we see far less of this conflict. A dog might be subject to differing impulses at the same time—the need to go outside, say, along with dread of a cold, dark night—but its internal conflicts seem incidental compared to the human world, where it is all-pervasive. Long would say that this is because we, unlike animals, are made up of entities that do conflict at times. They are, with their Hawaiian names:

1. Unihipili (pronounced oo-nee-hee-pee-lee). This is the lowest of the three selves in terms of evolution, discernment, and rational capacity: Long called it the “subconscious” or the “low self.” Dissecting the Hawaiian roots of this word, he determined that it controlled the energy supply of the human body. It is enormously strong, intuitive, and emotional. It can attach itself to another and act as a servant, but it can also be enormously willful and stubborn. Although it has little rational capacity, it controls the memories. It responds to visual imagery and particularly to physical stimuli (Long, Secret Science behind Miracles, 19).

2. Uhane (pronounced oo-hah-nay). This is the conscious self, or the “middle self.” It has the ability to speak (hane means to talk in Hawaiian), to reason, and, mostly importantly, to will. It is the master that directs the low self. While it possesses a person’s “executive capacity,” it has no physical strength of its own, but must receive it from the unihipili (Long, Secret Science behind Miracles, 165).

3. Aumakua (pronounced ah-oo-ma-koo-a). This is the High Self: the wise, utterly devoted, utterly loving, parental spirit. Its capacities and intelligence are far beyond those of both the unihipili and the uhane. Because it does not exist in the material world of time and space, it is capable of performing what are, to ordinary consciousness, miracles. Although from a lower point of view its power and abilities are divine, it is not to be worshipped but loved like a parent. It will grant anything if asked—except what will bring harm to self or others—but it must be asked. Otherwise it will stand aside and permit the lower selves to act out their free will (Long, Secret Science behind Miracles, 165).

Huna does not speak about entities higher than the aumakua. It leaves this question open on the premise that the High Self is the most exalted form of being that ordinary humans can imagine and that it does no good to speculate about anything higher.

Huna resembles some other systems that have not been directly influenced by it. The Hoffman Quadrinity Process, for example, a contemporary form of psychotherapy, posits an intellectual “adult,” an emotional “child,” and a higher “spiritual self,” which readily correspond to the huna triad. (The fourth element that makes up the quadrinity is the physical body.)

If one leaves out the High Self and considers the two lower entities alone, one will find even more correspondences. Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer, first published in 1934, instructs the would-be writer to balance the creative “unconscious” with the conscious, critical intellect. And the English writer and visionary Colin Wilson notes that the two hemispheres of the brain seems to represent different personalities with different abilities (Wilson).

While it is tempting to correlate the rational uhane with the left hemisphere of the brain and the irrational, creative unihipili with the right hemisphere, one should be cautious about jumping to conclusions when comparing different systems. Nevertheless, the resemblances do give cause for reflection.

If there are physical correlates to the two lower selves, is there also one for the High Self? Many esoteric traditions portray the High Self as located several feet about the crown of the head, so physical correlates may be less exact, if they exist at all.

One would think that, given the huna system, the way to get what you want would be for the uhane, the rational, conscious self, to ask the aumakua. In practice it does, but a certain peculiarity complicates the process.

This is quite simply the fact that the uhane cannot communicate directly with the aumakua. It must go through the unihipili, the low self. Because the unihipili thinks concretely, in visual images, the request is best framed as a picture—the “creative visualization” recommended by some New Age teachers (Gawain). One will be given exactly what one asks for, so it is necessary to frame the picture as specifically as possible and to consider all the ramifications of what one desires.

There is another fact to be considered: workings of this kind require energy. In Hawaiian, this vital energy is called mana, and it seems to come in three “voltages” correlated to each of the three selves that use it. But the ultimate source of energy in the human entity is the unihipili. The low self generates the power used by the middle self for willing and reasoning and by the High Self to perform miracles.

This, Long believed, was the ultimate source of the idea of sacrifice: to make one’s prayers manifest, one must accompany them with a charge of vital energy. The conscious self frames the request in the form of a picture, asks the low self to generate mana, and then directs the low self to send both image and energy to the High Self along the etheric aka cord, which links the three selves together.

As Heraclitus said, the way up and down are one and the same. One cannot reach the High Self without going through the low self. But where does ritual come in?

To answer this question, we must go back to Long’s description of the low self. As the self most closely connected with the body, it is strongly affected by physical stimuli. While it does listen to verbal or mental instructions from the conscious self, often these are so garbled and contradictory (just think of the random things that pass through your head on any given day) that it has learned to pay no attention to most of them. But the low self will take a suggestion seriously if it is accompanied by a physical stimulus.

This fact, I believe, goes far toward explaining the nature of ritual. It is tangible, it is physical, and at its best it attempts to communicate with the low self through all the senses. At a Catholic High Mass, for example, the eyes will see elaborate vestments and sacred vessels. The ears will hear chants, scripture readings, and hymns. The nose will smell incense. The sense of touch will be affected by the constant alternation of standing, sitting, and kneeling. Finally, the sense of taste will be brought in through eating the Eucharist. All of this is designed to gain access to the High Self—conceptualized as Christ—by way of the low self.

The success of a ritual in fact depends on how well it involves the low self. Long writes:

We should invent a ritual so definite to perform that it would take all the concentration of the low self—and thus prevent it from going through its action mindlessly with you while its mind, in its behind-the-scenes department, is really engaged with something different. Preliminary fasting, with sincere efforts to make amends for lacks and faults—all these are part of the gesture we make to arrive at the beginning of the successful prayer. I know of no way to convince the stubbornly literal low self that it and its man [sic] deserves an answer to prayer except by the performance of physical acts—the use of the acts as a physical stimulus. Remember, “faith without works . . .” (Long, Mana, 21)

This passage answers the question framed at the beginning of this article. If the ritual becomes too familiar, too mechanical, it will not only lose the middle self—whose conscious direction and will are required for the successful performance of the ritual act—but the low self as well. That’s why so many beautiful rituals are no more than that: they have been sapped of all volition and efficacy because they have become too familiar. Neither middle nor low self is involved.

The passage above brings up another point to be considered in ritual, which is that the low self really does regard the High Self as a parent, and while it will turn lovingly toward the High Self if its conscience is clear, it will skulk and hide if it is convinced it has done something wrong. How is that “something wrong” determined? By programming. Long tells the story of a young woman who had been raised as a devout Methodist, “looking upon dancing as a sin and drinking as a grave sin indeed. Her husband introduced her into a circle where drinking and dancing were the order of the day.”

At one point the woman tripped during a dance and twisted her ankle. After a few days it did not get better, and she went to a doctor, who, taking X-rays, found nothing wrong. Nonetheless, “in a short time,” Long says, “she could hardly walk” and developed “a strange, deep running sore below the ankle joint.” Medical treatment did no good.

It was only when a kahuna was called in that the woman began to show signs of improvement. The kahuna explained to her the huna code of ethics, which is quite simple: the only sin is to harm others. “If it hurt no one in any way, that act was not a sin” (emphasis Long’s).

The woman repeated the kahuna’s suggestion to herself, and after that point the ankle rapidly healed. Unfortunately, the woman’s Methodist conditioning was so deep-seated that when she went back to dancing and drinking, the problem returned. The only way she could keep her ankle well was to give up these activities for good (Long, Secret Science behind Miracles, 252–54).

A useful prologue to any ritual, then, would be some form of purification, setting accounts straight before one approaches the High Self. Forgiveness is useful: Christ’s injunction to pray, “Forgive us our debts as we have forgiven our debtors,” is good huna as well as good Christianity. Having forgiven others, the low self can turn to the High Self and feel entitled to forgiveness from it.

Long’s huna provides about as simple and elegant an account of why ritual works as I have seen. But it does leave one question in ambiguity: who is really in charge of a human being? Much of Long’s writings suggest that the middle self is in charge: ideally the low self does what it is told and the High Self grants what is requested if asked properly. But why should that be? While the middle self has remarkable powers of ratiocination, it is far inferior to the High Self in wisdom and even to the low self in perceptual abilities. (It is the lower self, not the middle self, that performs telepathic acts, finds lost things, and carries out similar tasks.) Why should the middle self be in charge?

The question is not merely hypothetical: it cuts to the heart of our being. In all of us there is a tension between our higher good—which often we do not know and do not even imagine—and what we think of as our good, which may not be good and may even be harmful. The middle self may have ideas about what is good for its future, but they may be quite different from what the High Self sees as good. How are these to be balanced?

Huna, at least in this form, is not entirely clear about this subject. It says that the High Self is willing to grant the middle self’s desires, but it also seems to suggest that the High Self can take over the direction of the human being and guide it in the course that is best for its evolution.

This ambiguity is not limited to huna. In it lies the whole difference between magic and religion. Magic can be seen as a means of acquiring what one’s middle and lower selves want through properly constructed ritual and prayer. With a religious outlook, on the other hand, one asks the High Self (however imagined) for what one wants but is ultimately willing to surrender to the High Self’s direction, even if it is different.

Few spiritual aspirants, I believe, practice either magic or religion in an entirely pure form. There is always a tension between asking for what one wants and surrendering to the guidance of the High Self, leaving it, with its vastly superior capacities, to achieve a good for us that we may not even imagine.

Perhaps it is even a mark of spiritual development to be able to turn over the controls in this way, since it requires that we admit the limits of our ordinary ways of seeing and being. It requires great faith and great understanding to be able to say to the High Self, “Not my will, but thine, be done.”

Sources

Brande, Dorothea. Becoming a Writer. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1934.

DeMoss, Tom. “The Big Kahuna: An Interview with Papa Auwae.” Gnosis 39 (spring 1996), 34–37.

Gawain, Shakti. Creative Visualization. Mill Valley, Calif.: Whatever Press, 1978.

Hertel, S.E. “Kahuna Ana’ana: The One Who Walks in Darkness; An Interview with Two Hawaiian Kahunas, Kahana and Pahia.” Gnosis 14 (winter 1990), 30–33.

Hoffman, Bob. No One Is to Blame. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1979.

Hoffman, Enid. Huna: A Beginner’s Guide. West Chester, Pa.: Whitford, 1976.

King, Serge Kahili. Changing Reality: Huna Practices to Create the Life You Want. Wheaton: Quest, 2013.

———. Happy Me, Happy You: The Huna Way to Healthy Relationships. Wheaton: Quest, 2014.

Long, Max Freedom. Growing into Light. Santa Monica, Calif.: DeVorss, 1955.

———. The Huna Code in Religions. Santa Monica, Calif.: DeVorss, 1965.

———. Mana, or Vital Force. Cape Girardeau, Mo.: Huna Research, 1981.

———. Psychometric Analysis. Santa Monica, Calif.: DeVorss, 1959.

———. The Secret Science at Work. Marina del Rey, Calif.: DeVorss, 1953.

———. The Secret Science behind Miracles. Los Angeles: Huna Research Publications, 1948.

———. Self-Suggestion and the New Huna Theory of Mesmerism and Hypnosis. Vista, Calif.: Huna Research Publications, 1958.

Vitale, Joe. The Art and Science of Getting Results: The Nine Most Powerful Ways to Clear Blocks to Your Success. New York: Gildan, 2020. See especially chapter 5.

Wilson, Colin. “The Laurel and Hardy Theory of Consciousness.” In The Essential Colin Wilson. Berkeley, Calif.: Celestial Arts, 1986. 168–79.

Richard Smoley’s latest book is A Theology of Love: Reimagining Christianity through A Course in Miracles”. The author wishes to thank the late Murray Korngold, PhD, for his advice and assistance with this article. An earlier version of this article appeared in Gnosis: Journal of the Western Inner Traditions 11 (spring 1989).

Constructing an Effective Ritual

The touchstone of a successful ritual is, of course, the practitioner’s own being: what speaks most deeply to you—especially to your low self—is what will work. But it is possible to set out a broad framework of what is needed for a successful ritual, at least according to huna. Ritual should include:

1. Some form of purification. The practitioner should be able to feel that he or she can look the radiant High Self square in the eye: otherwise the low self will not feel worthy of the blessings it is asking for. Forgiveness of others is one way, but in the case of people one has wronged, it may be necessary to make reparations of some kind. If this cannot be done, some form of charity or penance may be helpful.

2. Deciding exactly what you are asking for. This must be as specific as possible to win the attention of the low self. Moreover, if details are not specified, the prayer can backfire. It is also necessary to visualize your desire as an accomplished fact, not as something that will happen in the future. The low self is so literal-minded that if the desire is visualized as being in the future, the low self will keep it there.

3. Obtaining the cooperation of the three selves. Relaxation is helpful here, and some technique for achieving it, such as deep breathing, can be helpful. Meditate upon the High Self to draw it near. Often it is pictured as some eight to ten feet above the crown of the head. The cooperation of the low self should be obtained. This might be done by speaking to it or by thanking it for the valuable services it performs (maintaining vital functions, supplying creativity and memory). It is important that the low self feels reassured and loved.

4. Generating an extra supply of mana to be sent to the High Self. Techniques for this vary; someone who is expert in physical disciplines may be able to do it by sheer willpower. Otherwise, deep breathing or vigorous exercise can work. Here is a method described by Long:

Stand with feet very wide apart and arms extended level with the shoulder, palms angling slightly upward, if that is an easy and natural position for you . . . When this position is taken, say aloud, “The universal life force (or just say Mana) is flowing into me now . . . I feel it.” Repeat this about four times, slowly, and with a pause of about twenty seconds between repetitions. Expect to accumulate a surcharge, and expect to feel a prickling in the palms of your hands or wrists, to indicate the building up of the charge (Long, Mana, 8).

6. Making a mental picture of the object or result desired. Again, it should be visualized as already having happened.

7. Sending the thought. You can imagine it being transmitted up the aka cord—an etheric thread running up through the crown of the head to the High Self. Feel both the thought and energy being transmitted.

8. Thanking the High Self for accomplishing what is desired. It is also useful to let the energy flow down from the High Self to the lower selves. The kahuna formula was to say, “Let the rain of blessings fall” (Long, Mana, 32).

The power of ritual resides in its personal, subjective content and meaning; thus the more evocative you can make the surroundings, the more of a charge you can put into the prayer, and the more likely it is to work.

Of course you will want to vary details, but the items above provide a general framework for huna prayer. It is wise not to make the process too elaborate: most prayers of this kind should be repeated every day until the desired result is accomplished, and a ritual with too many details may be too cumbersome to be worked so often. As a compromise, you may want to perform a more elaborate ritual, with items such as candles and incense, the first time, and then do it afterward in a simpler form.

Richard Smoley

Huna and Theosophy

The main article describes the basic huna system described in Long’s books, but the full picture is somewhat more complex.

There are, as noted, three selves: the lower self, the middle self, and the High Self. But, Long says, each of these three selves also possesses “its own invisible or ‘shadowy’. . . body. During life the shadowy bodies of the low and middle selves interblend with the physical body. After death the selves live in their shadowy bodies. The High Self lives at all times in its shadowy body. It may never contact the physical body, but it never resides in it.”

Furthermore, “huna recognizes three kinds of vital force, one kind for the use of each of the three selves,” although “all of these are called mana.”

In the full-blown system, then, there are the three selves, their three shadowy bodies, and their three kinds of mana. With the physical body added, the human entity consists of ten elements.

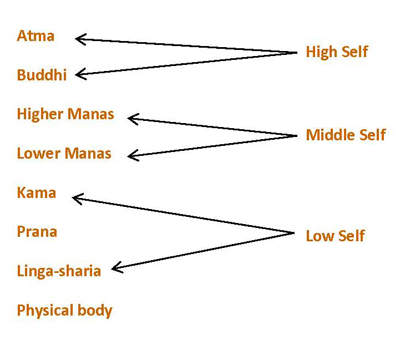

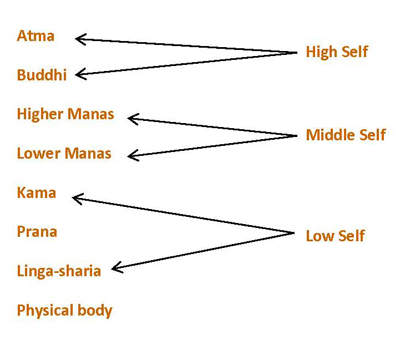

Long compares this system with the familiar Theosophical seven-part division of the human being: atma, buddhi, manas, kama, prana, the linga-sharira, and the physical body. He correlates his system with that of Theosophy by equating atma with the High Self; buddhi with the middle self; and manas, along with kama, with the lower self.

Each of the three selves in huna has its own etheric body, as well as its own form of mana (which is similar to the Theosophical concept of prana).

Long’s correlation is not entirely satisfactory, because the Theosophical buddhi is generally seen as a higher entity than the middle-level conscious self. The accompanying diagram might offer a better correlation: the basic huna system, for example, says that the low self is the one that has access to, and generates, life force.

In the end, these equations are merely approximate, because the systems differ on many points. Huna, like many shamanic traditions, holds that the lower and middle selves go their own ways after physical death, rather than dissolving, as classic Theosophy holds.

When comparing systems like these, it’s valuable to look for similarities and correspondences, but it’s a mistake to try to squeeze one system entirely into the box of another.

For Long’s treatment of these points, see The Huna Code in Religions, 20–21, 40–44.

Richard Smoley

As I step out of the tub at the foot of the mesa, sun waning and air chilled and frozen, I realize I am partaking in what has been a healing ritual of the ancients for centuries. There is a comfort here in the healing properties of the hot, earthborn mineral waters, and in knowing that natives before me have soaked in these stone baths as a practice rooted in the bounty of Mother Earth.

As I step out of the tub at the foot of the mesa, sun waning and air chilled and frozen, I realize I am partaking in what has been a healing ritual of the ancients for centuries. There is a comfort here in the healing properties of the hot, earthborn mineral waters, and in knowing that natives before me have soaked in these stone baths as a practice rooted in the bounty of Mother Earth.

The global crisis with Covid 19 has shown us all that we are not in control, regardless of our age, race, gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. In other words, Covid 19 provided us with the opportunity to realize that all of us are essentially the same: human beings. For those who are spiritually inclined, this essential unity comes as no surprise. We recognize that beyond our sameness as human beings, we are united as aspects of the Divine (regardless of the name one might choose to use), and all of us are moving toward conscious awareness of this unity. We move toward this awareness through transformation of our consciousness, which occurs when we face difficulties and tribulations.

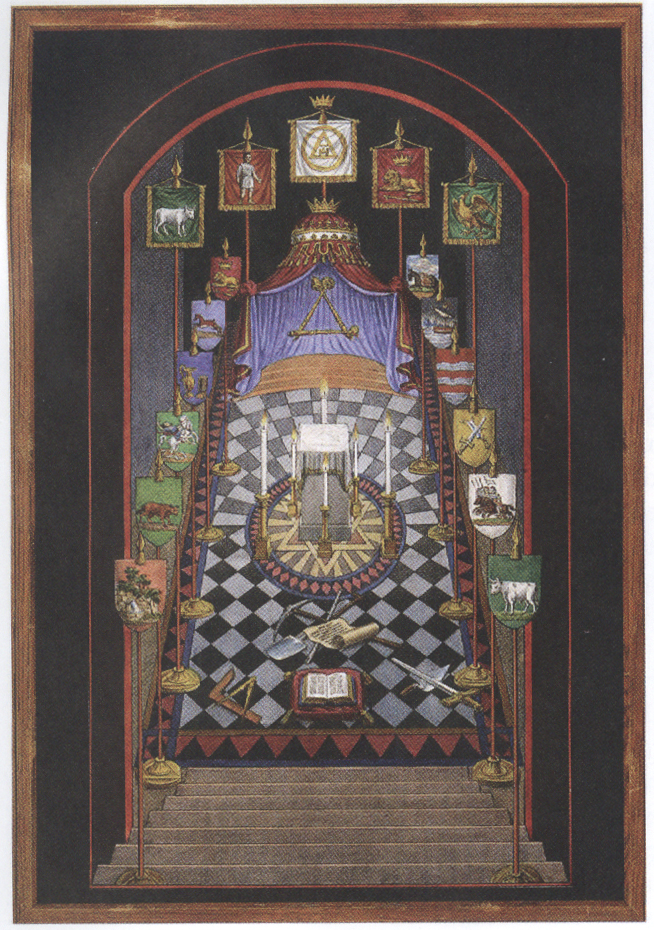

The global crisis with Covid 19 has shown us all that we are not in control, regardless of our age, race, gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. In other words, Covid 19 provided us with the opportunity to realize that all of us are essentially the same: human beings. For those who are spiritually inclined, this essential unity comes as no surprise. We recognize that beyond our sameness as human beings, we are united as aspects of the Divine (regardless of the name one might choose to use), and all of us are moving toward conscious awareness of this unity. We move toward this awareness through transformation of our consciousness, which occurs when we face difficulties and tribulations. My involvement with the Co-Masonic order began in a strange and unique way, as many spiritual quests do. One afternoon, while I was browsing in a bookshop, a copy of The Egyptian Book of the Dead suddenly toppled off a shelf into my hands. A short time later my search led me to the local branch of the Theosophical Society in my hometown of Detroit.

My involvement with the Co-Masonic order began in a strange and unique way, as many spiritual quests do. One afternoon, while I was browsing in a bookshop, a copy of The Egyptian Book of the Dead suddenly toppled off a shelf into my hands. A short time later my search led me to the local branch of the Theosophical Society in my hometown of Detroit.

The word ritual can evoke mysterious power: the smell of incense, the pageantry of ceremonial robes, the resonance of prayers muttered in a low singsong. But the word can also connote something dead and stultifying, actions carried out for the sake of form without any remembrance of the meaning behind them.

The word ritual can evoke mysterious power: the smell of incense, the pageantry of ceremonial robes, the resonance of prayers muttered in a low singsong. But the word can also connote something dead and stultifying, actions carried out for the sake of form without any remembrance of the meaning behind them.