Printed in the Fall 2020 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Gomes, Michael , "Ancient Wisdom for a New Age: Theosophical Translations of Hindu Scriptures" Quest 108:4, pg 19-23

By Michael Gomes

At its inception in 1875, the object of the Theosophical Society was “to collect and diffuse a knowledge of the laws which govern the universe.” It was not an attempt to replicate what was already being done but to investigate areas left unexplored at the time. When the headquarters of the Society was established in India in the 1880s, the Objects began to look more as they do today. Only the Second Object was markedly different from how it now stands: “To promote the study of Aryan and other Eastern literature, religions and sciences and vindicate its importance.” It remained that way during H.P. Blavatsky’s lifetime, only changing in 1896 to its current injunction to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

At its inception in 1875, the object of the Theosophical Society was “to collect and diffuse a knowledge of the laws which govern the universe.” It was not an attempt to replicate what was already being done but to investigate areas left unexplored at the time. When the headquarters of the Society was established in India in the 1880s, the Objects began to look more as they do today. Only the Second Object was markedly different from how it now stands: “To promote the study of Aryan and other Eastern literature, religions and sciences and vindicate its importance.” It remained that way during H.P. Blavatsky’s lifetime, only changing in 1896 to its current injunction to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

In her Key to Theosophy, Blavatsky cites the work of the library at the TS headquarters in Adyar, India, and at local branches to collect works on ancient philosophies, traditions, and legends. She also specifies the need to make available translations, original works, extracts, and commentaries based on this material in order to help realize the Second Object.

Theosophists set to work to fulfill this promise and have produced a number of original translations of Hindu scriptures. Two texts received the most attention: the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali.

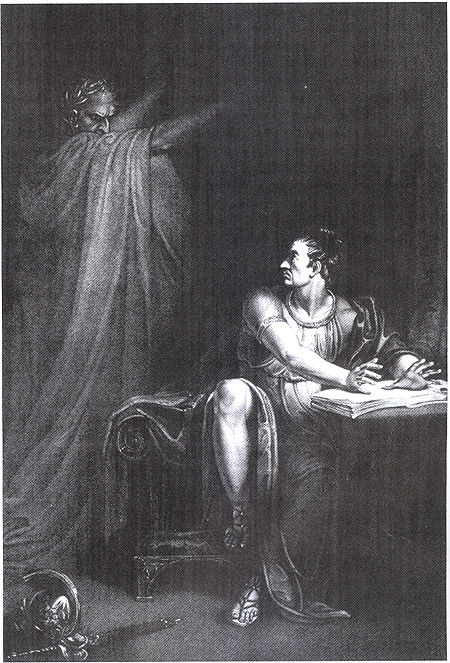

The Bhagavad Gita forms part of the great Indian epic the Mahabharata. Its setting is a battlefield, as two great clans prepare for war. In its totality, the Mahabharata is the story of families torn apart, a kingdom lost at a throw of the dice, brave heroes, and a return to righteousness. The Gita appears in the sixth book, in the form of a dialogue between the warrior Arjuna, who is about to take up arms against his cousins, and his charioteer, Krishna. Extracted from the larger narrative, the text has been taken as a summation of Hindu philosophy and has gone on to become a global resource for spirituality.

The Gita was one of the first Hindu scriptures translated into English: one edition appeared in 1785. The text was familiar to the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, who commented on it. It was also known to the New England Transcendentalists: Henry David Thoreau mentions it in Walden, published in 1854. In the 1880s, Edwin Arnold produced a popular verse rendering entitled The Song Celestial.

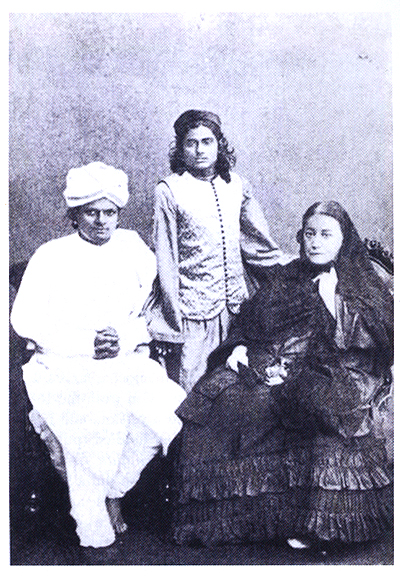

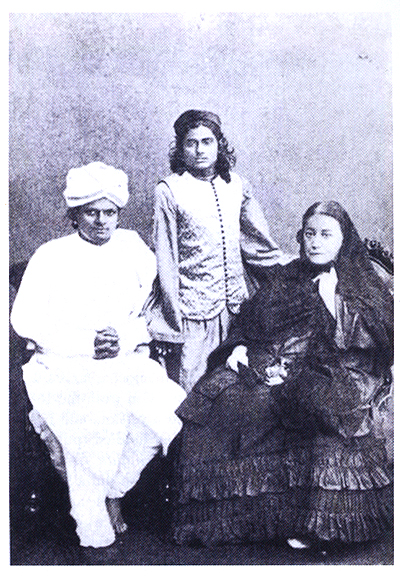

Translations by Theosophists offered another perspective and introduced the text to a wider audience. The key had been supplied by the distinguished Indian member T. Subba Row (1856–90). In a series of lectures delivered at the annual Madras Convention of the Society in 1885 and 1886 he suggested that Arjuna represented the individual soul, “the real monad in man,” while Krishna represents the Logos, “the spirit that comes to save man.” Using this allegorical approach, Subba Row depicted the Gita as a work of practical guidance, indicating “that the human monad must fight its own battle, assisted once he begins to thread the true path by his Logos” (Subba Row, 2:391). These lectures were printed in The Theosophist and issued in book form in 1888 as Discourses on the Bhagavad Gita.

| |

|

| |

From left: T. Subba Row; an early disciple, known variously as Babaji, M. Krishnamachari, S. Krishnamachari, S. Krishnaswami Iyengar or Aiyangar, and Darbhagiri Nath; and HPB. |

By this time Theosophists had their own translation of the Gita, by a young Bengali named Mohini Chatterji. Chatterji, who was, like HPB, a pupil of the Mahatmas, had been brought to Europe in 1884 by her. He traveled to America, where he produced his translation in 1887. It included a lengthy commentary, often assisted by numerous references to the New Testament. Chatterji said that the text illustrated the idea that “human nature is one, God is but one, and the path to salvation though many in appearance, is really but one” (Chatterji, 276).

William Q. Judge’s rendition of the Gita, published in 1890, utilized previous translations. It was an inexpensive pocket-sized book, which could be carried everywhere. Judge observed that the Gita depicted “the struggle which is inevitable as soon as any one unit in the human family resolves to allow his higher nature to govern his life” (Judge, ix).

Judge’s rendition was followed by Annie Besant’s in 1895. For Besant, the keynote of the Gita was moderation and the “harmonising of all the constituents of man, till they vibrate in perfect attunement with the One, the Supreme Self” (Besant, viii). Another version was issued by Besant and the Hindu scholar Bhagavan Das, with the Sanskrit text, a free English rendering, and a word-for-word translation, which appeared in 1905 and revised in 1926.

The translations of Judge and Besant remain in print, but other attempts by Theosophists did not receive as wide a circulation. Charles Johnston, who had served in the British Civil Service in India and had studied Sanskrit, published his translation in New York in 1908, and F. T. Brooks, best remembered as the tutor of the future statesman Jawaharlal Nehru, published his in India in 1909. Alfred E.S. Smythe, general secretary of the TS in Canada and a veteran newspaper editor, issued a “conflation” in 1937 based on previous English editions. Ernest Wood, who had worked at the Theosophical headquarters in India, published his translation in 1954.

Text encouraged context, and a wealth of commentaries by Theosophists elucidated the message of the Bhagavad Gita. Mention has already been made of the influence of T. Subba Row. In 1893 the Kumbakonam Branch in South India issued Thoughts on the Bhagavad Gita by “A Brahmin F.T.S.” (Fellow of the Theosophical Society) based on a series of lectures before the group. The author’s interpretation was based on the Puranas, the great repositories of Hindu lore, and The Secret Doctrine. “H.P.B. talked the same thing as our ancient Brahminical philosophers in a different language and from a different platform” (Brahmin F.T.S., 78). Three volumes of Studies in the Bhagavad Gita, by another Indian member, “The Dreamer,” bearing the subtitles of The Yoga of Discrimination (1902), The Yoga of Action and Occultism (1903), and The Path of Initiation (1904), appeared under the imprint of the Theosophical House in London. These followed the approach of Subba Row, with Hindu and Theosophical concepts illuminating the text.

Bhavani Shankar (1859–1936), a disciple of Blavatsky, lectured on the Bhagavad Gita throughout India after her death. A biographical note in one of the volumes of his talks says that “he was initiated into some of the hidden laws and secret practices of Raja-Yoga by the famous mystic, Subba Row” (Basu, ix). Shankar saw a deep longing for and devotion to Wisdom as a prerequisite for understanding the subject. Judge and Besant also wrote their own commentaries on the book. Even Rudolf Steiner lectured on it.

Theosophical renderings of the Gita are instructive in the level of interpretation that they offer. At one point, overwhelmed by what Krishna reveals to him, Arjuna seeks to understand his divine nature. Krishna responds (11.32): “I am Time, destroyer of the worlds grown ripe for death,” in Smythe’s edition. Judge gives, “I am Time matured, come hither for the destruction of these creatures,” while Besant has, “Time am I, laying desolate the world, made manifest on earth to slay mankind.” Compare a newer translation by Ravi Ravindra, published in 2017: “I am Time, the Destroyer of worlds, come forth here with the will to annihilate the nations.”

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra

The only other Hindu scripture to receive as many Theosophical translations as the Bhagavad Gita was the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali. If the Gita offered a moral compass in times of stress, the Yoga Sutra gave practical instruction in mind control. Theosophists were among the first to bring the idea of yoga to the West.

The date of the text and its author are still debated. The general consensus for the text is between 450 and 350 BCE, but Blavatsky pushes the date for Patanjali even further back. The Theosophical Glossary gives it as “nearer to 700 than 600 B.C.” (Blavatsky, Glossary, 251).

W.Q. Judge’s 1889 version, The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali, was based on an earlier version printed in India. Like his edition of the Gita, it was issued as a pocket-sized book. Judge’s simple language offered clear instruction on the training of the mind, and its influence on the burgeoning New Thought and Mental Science movements in America should be noted.

Manilal Dvivedi’s translation, published in India a year later, aimed to be a more accurate portrayal of the text, and it was kept in print by the Theosophical Society till the 1940s. Dvivedi (1858–98), a noted Gujarati author and advocate for education and social reform, also found time to produce a number of erudite translations of Sanskrit texts.

Charles Johnston’s 1912 rendition was more free-flowing. As indicated by the subtitle, The Book of the Spiritual Man, Johnston saw the text as a call to spiritual aspiration. I.K. Taimni’s 1961 The Science of Yoga offered a translation and commentary “in the light of modern thought.”

Two Theosophically related attempts are Mabel Collins’ Transparent Jewel (1912), which was an extended rumination on the subject using Dvivedi’s translation, and Alice Bailey’s 1927 The Light of the Soul: Its Science and Effect, which described itself as a “paraphrase” of Patanjali, and looks at the book as a manual of esoteric training as interpreted through Bailey’s system of seven rays and esoteric astrology.

Yogi Ramacharaka (a pen name of the American metaphysical writer William Walker Atkinson, 1862–1932) blurred the lines between Theosophy, Yoga, and New Thought in his series of instructional books from Chicago’s Yogi Publishing Company at the beginning of the twentieth century.

To compare Theosophical versions of the Yoga Sutra: Judge gives for sloka (verse) 2.1, which distills the methodology that applies to the practitioner: “The practice of Concentration [Judge’s rendering of yoga] is, Mortification, Mutterings, and Resignation to the Supreme Soul.” Dvivedi has, “Mortification, study and resignation to Isvara [the personal God], constitute practicing Yoga.” Johnston’s version reads, “The practices which make for union with the Soul are: fervent aspiration, spiritual reading, and complete obedience to the Master.” A more recent example (though not by a Theosophist), Barbara Stoler Miller’s 1996 Yoga: Discipline of Freedom, which is now regarded as a classic, reads: “The active performance of yoga involves ascetic practice, study of sacred lore, and dedication to the Lord of Yoga.” (The terms “mortification” and “ascetic practice” are a translation of the Sanskrit tapas, a word whose Vedic origins indicate heat. It has been suggested that ardor or fervor might be truer to its meaning. “Those who practice tapas could be described as ‘ardent,’” writes Roberto Calasso, 99.)

By the 1930s, Theosophical efforts on the study of yoga were eclipsed by the arrival of a succession of yogis and swamis from India. The efforts of, first, Swami Vivekananda and then of Paramahansa Yogananda, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and others led to the emergence of homegrown adherents. The 1959 Yoga for Americans by Indra Devi (Eugenia Peterson) presented the subject as compatible with the lifestyle of the period, and Theos Bernard’s 1944 Hatha Yoga advocated for the postures as part of a fitness regime. They prepared the way for the next wave of instructors from India, such as B.K.S. Iyengar, whose 1965 Light on Yoga included over 600 photographs illustrating the asanas.

It was now possible to speak of yogas in the plural, and Ernest Wood codified seven variants: the Raja Yoga of Patanjali, the Karma and Buddhi Yogas of Sri Krishna, the Jnana Yoga of Sri Sankaracharya, Hatha Yoga, Laya (Kundalini) Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, and Mantra Yoga (Wood, 12).

No other Sanskrit texts were as popular among Theosophists as the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutra. The Vivekachudamani (“The Crest Jewel of Wisdom”), once attributed to the Indian sage Shankaracharya, is still in print in Mohini Chatterji’s translation from the 1880s. Charles Johnston also produced a version, and Ernest Wood was working on one when he died (published posthumously as The Pinnacle of Indian Thought by Quest Books in 1967). Johnston also did a free rendering of the Upanishads, as did G.R.S. Mead in 1896. I.K. Taimni translated the Siva Sutras (1976), the Bhakti Sutra (1975), and the Pratyabhijnahrdayam as The Secret of Self-Realization (1974), all issued by the Theosophical Publishing House in Adyar, India. Radha Burnier and Richard Brooks also produced a Sanskrit/English version of the Pratyabhijnahrdayam.

For the early Theosophists, translations of Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutra offered access to the Ancient Wisdom discussed by Blavatsky and others. It also presented a validation for Theosophical concepts, many of which were found in these texts. But as the late TS president N. Sri Ram has noted, this Ancient Wisdom does not base its claim on mere antiquity. “The word ‘ancient’ applied to it conveys the significance of a wisdom accumulated through the ages, tested and proved by time” (Sri Ram, 186).

The ideas in texts like the Gita found resonance in Theosophical writings. Members would have related injunctions given in the Gita to that in works like Light on the Path (1885), a guide to the spiritual life that urges the pupil to “stand aside in the coming battle, and though thou fightest be not the warrior” (2.1). Theosophical interpretations, which were not moored in sectarian differences, would add their own nuances.

Mme. Blavatsky had differentiated the aspects of yoga early on. Commenting on an article on the subject that she published in The Theosophist in 1882, she utilized the terms raja and hatha yoga to distinguish her work from more mundane forms. She told her students, “He who has studied both systems, the Hatha and Raja-yogas, finds an enormous difference between the two: one is purely psycho-physiological, the other purely psycho-spiritual” (Blavatsky, Esoteric Instructions, 135). Elizabeth de Michelis, in A History of Modern Yoga, and others have pointed out that when Hindu teachers such as Vivekananda came west, they adapted their message to the already existing terminology of Theosophy.

The effects of Theosophical interest in Hindu scriptures would not remain limited to the Theosophical Society. In his Story of My Experiments with Truth, Mohandas Gandhi relates how while he was a young law student in England, he was approached by two Theosophists who were studying the Gita. They wanted him to read the original with them. He confessed that he had never read the book either in the original Sanskrit or his native Gujarati. When he studied the book with them, it revealed its worth to him, and it became an “infallible guide of conduct” and “dictionary of daily reference” (Gandhi, 323). Its principles of nonattachment and equanimity can be seen in his ideas about satyagraha, which he used to gain Indian independence, and which influenced others, including Martin Luther King Jr. and the American civil rights movement.

The diffusion of the Gita into contemporary society can be seen in the words of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American physicist known as “the father of the atomic bomb.” He relates that when he witnessed the first atomic blast, Krishna’s words from the Gita came to mind, “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.” This ancient Hindu scripture had found new context and had truly entered a new age. Through their translations and commentaries, Theosophists had contributed to its becoming a part of the public discourse.

Sources

Basham, A.L. The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism. Boston: Beacon, 1989. Basham suggests we view the Gita as “a compilation by more than one hand, with at least two main authors whose doctrines are very different” (95).

Basu, Upandranath. Foreword to Pandit Bhavani Shankar, Lectures on the Bhagavad Gita. Uttarpara, India: Uttarpara Theosophical Lodge, 1923. Bhavani Shankar’s lectures have been collected and republished as The Doctrine of the Bhagavad Gita. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Concord Grove Press, 1984.

Besant, Annie. The Bhagavad Gita, or the Lord’s Song. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1896.

Blavatsky, H.P. Esoteric Instructions. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 2015.

———. The Theosophical Glossary. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1891.

“A Brahmin F.T.S.” Thoughts on the Bhagavad Gita. Kumbakonam, India: Kumbakonam Branch of the Theosophical Society, 1893.

Calasso, Roberto. Ardor. Translated by Richard Dixon. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2014.

Chatterji, Mohini M. The Bhagavad Gita, or The Lord’s Lay. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1887.

Gandhi, Mohandas. Gandhi’s Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1948.

Judge, W.Q. The Bhagavad Gita: The Book of Devotion. New York: The Path, 1890.

Oppenheimer, J. Robert. “Oppenheimer Bhagavad-Gita Quote,” YouTube, accessed June 29, 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pqZqfTOxFhY.

Sharpe, Eric J. The Universal Gita: Western Images of the Bhagavad Gita. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, 1985.

Sri Ram, N. A Theosophist Looks at the World. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1950.

Steiner, Rudolf. The Occult Significance of the Bhagavad Gita. New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1968. Based on talks given in May and June 1913.

Subba Row, T. T. Subba Row: Collected Writings. 2 vols. San Diego: Point Loma Publishing, 2001.

Wood, Ernest. Seven Schools of Yoga. Wheaton: Quest Books, 1976. This is a reprint of his The Occult Training of the Hindus, published in India in 1931.

Michael Gomes is director of the Emily Sellon Memorial Library in New York. He has authored eight books and numerous articles and monographs on H.P. Blavatsky, Theosophy, and the Theosophical Society, and he is working on his ninth.

Cherry Gilchrist’s image of a ruined city on a riverbank in this issue reminds me of some thoughts I put into my book How God Became God: What Scholars Are Really Saying about God and the Bible.

Cherry Gilchrist’s image of a ruined city on a riverbank in this issue reminds me of some thoughts I put into my book How God Became God: What Scholars Are Really Saying about God and the Bible.

I earned a PhD in evolutionary biology at a major Midwestern university. Later I was introduced to Theosophy. I was distraught to learn that some evolutionary concepts as understood by Theosophy differed widely from contemporary scientific fact and theory. This contentious material was prominently featured in The Secret Doctrine. I was particularly concerned with the elaborate narratives concerning human evolution in earlier Root Races, which read like children’s stories. The chasm separating evolution as understood by biology and anthropology and that in The Secret Doctrine continues to widen, and the two versions seem irreconcilable.

I earned a PhD in evolutionary biology at a major Midwestern university. Later I was introduced to Theosophy. I was distraught to learn that some evolutionary concepts as understood by Theosophy differed widely from contemporary scientific fact and theory. This contentious material was prominently featured in The Secret Doctrine. I was particularly concerned with the elaborate narratives concerning human evolution in earlier Root Races, which read like children’s stories. The chasm separating evolution as understood by biology and anthropology and that in The Secret Doctrine continues to widen, and the two versions seem irreconcilable. Many seekers today set out on their paths to find something that society is not giving them. In the face of ecological destruction, unflinching individualism, and a general sense of separation and desperation, people are looking for something not quite so tragic as what is currently on the table. Religion and its close cousin, literature, are the great resources in the human search for dignity and meaning. Myth, poetry, and drama can be powerful pathfinders out of this seemingly modern malaise, because they tell us that this search for something more is not ours alone but is woven into the fabric of human existence.

Many seekers today set out on their paths to find something that society is not giving them. In the face of ecological destruction, unflinching individualism, and a general sense of separation and desperation, people are looking for something not quite so tragic as what is currently on the table. Religion and its close cousin, literature, are the great resources in the human search for dignity and meaning. Myth, poetry, and drama can be powerful pathfinders out of this seemingly modern malaise, because they tell us that this search for something more is not ours alone but is woven into the fabric of human existence.

At its inception in 1875, the object of the Theosophical Society was “to collect and diffuse a knowledge of the laws which govern the universe.” It was not an attempt to replicate what was already being done but to investigate areas left unexplored at the time. When the headquarters of the Society was established in India in the 1880s, the Objects began to look more as they do today. Only the Second Object was markedly different from how it now stands: “To promote the study of Aryan and other Eastern literature, religions and sciences and vindicate its importance.” It remained that way during H.P. Blavatsky’s lifetime, only changing in 1896 to its current injunction to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

At its inception in 1875, the object of the Theosophical Society was “to collect and diffuse a knowledge of the laws which govern the universe.” It was not an attempt to replicate what was already being done but to investigate areas left unexplored at the time. When the headquarters of the Society was established in India in the 1880s, the Objects began to look more as they do today. Only the Second Object was markedly different from how it now stands: “To promote the study of Aryan and other Eastern literature, religions and sciences and vindicate its importance.” It remained that way during H.P. Blavatsky’s lifetime, only changing in 1896 to its current injunction to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

Many years ago, in a seminar at the New York Theosophical Society, a woman told about a spontaneous memory from the time before she was born. “I saw a vision of what I had to accomplish and what the difficulties would be. I remember saying, ‘Yes, I agree to this.’”

Many years ago, in a seminar at the New York Theosophical Society, a woman told about a spontaneous memory from the time before she was born. “I saw a vision of what I had to accomplish and what the difficulties would be. I remember saying, ‘Yes, I agree to this.’”