Channeling the Waters of Wisdom: Ancient Lineage and the Transmission of Knowledge

Printed in the Fall 2020 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Gilchrist, Cherry, "Channeling the Waters of Wisdom: Ancient Lineage and the Transmission of Knowledge" Quest 108:4, pg 10-14

By Cherry Gilchrist

Over the last few years, along with a small group of colleagues, I’ve been looking into the history of our esoteric lineage. Since the 1970s and ’80s, we’ve been members of what is said to be a very old line of transmission: a particular tradition of wisdom which could broadly be described as Kabbalistic. We know certain facts about how it’s been passed down within the last seventy years, and we have records and reminiscences of those who were involved in the decades before we ourselves came along, from the 1950s onwards. But tracing the trail before that is difficult.

Over the last few years, along with a small group of colleagues, I’ve been looking into the history of our esoteric lineage. Since the 1970s and ’80s, we’ve been members of what is said to be a very old line of transmission: a particular tradition of wisdom which could broadly be described as Kabbalistic. We know certain facts about how it’s been passed down within the last seventy years, and we have records and reminiscences of those who were involved in the decades before we ourselves came along, from the 1950s onwards. But tracing the trail before that is difficult.

I’ve long been interested in lineage, and while my teacher was still alive, I pestered him for information. He occasionally threw a clue or two in my direction. “Sometimes,” he told me, “the tradition is only passed on to two or three people in a generation. Then sometimes there’s a more widespread need for it.” Our time, he implied, was one when the work of the tradition needs to go out further into the world at large. He himself was taught Tree of Life Kabbalah by, of all people, a farmer in Yorkshire while he, my teacher, was still a young man serving in the British Royal Air Force. On his release from the RAF in his late twenties, he helped to set up groups in London whose recruits first gathered in the coffee bars of London’s Soho district in the late 1950s. In terms of our research, so far, so good: we have chronicled this starting point, and from the research gathered, a website is now set up to detail how the trail led from there into a branching network of groups and teachers whose output is also found in books, films and follow-on organizations. They include the Toledano School of Kabbalah, headed by Warren Kenton (Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi); the Alef Trust, which teaches courses on consciousness and transpersonal and spiritual psychology; and the Praxis Research Institute, which explores the roots of esoteric Christianity. (See the Soho Cabbalists website for more information).

But how do we take this back further? How is such a lineage passed on? What impulse gave rise to it, since it is said to date back 6,000 years? These are big questions, and there are no exact answers. My intention here is to introduce some ways of considering these links. Often the questions are more important than the answers. We can keep asking questions, and even if the answers aren’t exactly as expected, they can help to illuminate the path. The motto of the first Soho group was: “There’s always further to go.”

Here’s a question to begin with: what is wisdom itself?

Wisdom from on high,

who orders all things mightily,

to us the path of knowledge show,

and teach us in her ways to go.

This is a verse from an ancient Christian antiphon, which is sung in the season of Advent. Wisdom, it says, can show us a path of knowledge. To look at this in a slightly different way, it’s often an individual experience of wisdom which leads us into a particular spiritual path. Perhaps we unexpectedly receive some wise counsel, or experience a moment of grace, or have a significant encounter. Whatever it is points the way to something greater, as if it has come to us from the working of wisdom itself in the universe.

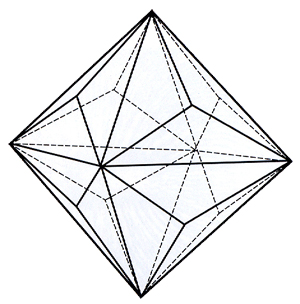

Wisdom can thus trigger an initiation, an entry point into a particular lineage. But it is not itself a lineage; it isn’t bounded in this way. It’s easier to use a model to explain how I perceive this, so my reference here is the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. It doesn’t matter if you are not familiar with this, as I’m just going to describe the first three principles of creation, the forces that enter the created universe and shape it in primordial terms. The Tree itself consists of ten such sefirot or “spheres,” as they are known. In these terms, the first sefirah is Keter (“Crown”), the divine presence entering and “crowning” our universe, as its name signifies. Then Wisdom, Hokhmah, comes forth from that, as the first active manifestation in this universe. It is an outpouring, which is bountiful and unceasing, but which has no defined form. This flow is then tempered, shaped, and nurtured by Binah (“Understanding”), also sometimes known as the Great Mother.

When these first three principles—divinity, wisdom, and understanding—are established in their prime configuration as a triad, then Knowledge comes into existence, at the point of Da’at. This is not a sefirah in its own right, but a kind of gateway or abyss, which lies between the supernal world above and our familiar human world below. Seeing how these three forces combine to give rise to knowledge is useful here in helping us see how a spiritual path is shaped.

To begin with, though, I would like to explore the nature of wisdom from our very imperfect human standpoint. There are different ways to define wisdom, but as it is boundless in itself, there is no final way of pinning it down. This is because each expression of wisdom is a unique, creative response to a situation. A drop of wisdom can transform a particular situation at that particular moment in time, whereas another such moment requires a different drop of that holy essence. If you think of someone who you consider to be wise, how does their wisdom express itself? Probably never the same way twice, and sometimes in a completely unexpected way, but one which seems perfect for the situation. Wisdom is not a predictable stock response, and definitely not a checklist of dos and don’ts. A wise person answers in different ways at different times. And let us not confine wisdom to “teachers.” Everyone has moments of uttering words of wisdom, sometimes not knowing exactly where they come from.

My own image of wisdom, in visual terms, is as a kind of pearly, luminescent outpouring. It can be channeled like water, but it cannot be shaped like clay. I would guess that many of us have some kind of similarly instinctive response to the word, even though our images of it may be different, because we have an innate human capacity to recognise wisdom, whether or not we choose to ignore or deny it. (And that does happen.) We may also experience a sense of “rightness” when we come across true wisdom, even if it flies in the face of conventional dictates or what we personally would wish for. Wisdom in action has a power which can move us to tears, or bring a sense of calm that stills all previous turbulence. This inborn ability to know wisdom can also help us recognize a true spiritual path, which is not always an easy task, especially if we encounter a hidden or esoteric tradition that has been rejected by established religion. But we can consult this inner barometer of wisdom to help decide whether it’s a path that can be trusted.

As I write this, I find myself floating on what seems an endless sea of possibilities. I could discuss wisdom in this way or that, explore a range of ideas, track down innumerable sources, and possibly drown in the attempt! So like Binah in those first Kabbalistic principles, I have set limits here so as to keep to the theme of transmission of lineage.

Moving on, therefore, I am going to offer three stories which have emerged within the lineage that I have worked and studied in, and which may help to explain the relationship between spiritual work and the channeling of wisdom into a tradition. Where historical fact fails us, symbols and legends may illuminate its development.

The Ruined City

This image came into my mind spontaneously some years ago:

There’s a ruined city standing on a riverbank. It’s empty: no one’s there, and all around it the land is bare, like a sandy desert. The walls are half broken, and there are no roofs on the buildings. But the river is still flowing past between its banks. The river is full, and there’s a strong current, even though the land around is empty and barren.

My teacher nodded as I described it to him later. “Yes,” he said, “that’s how our line of work goes.”

From this and later conversations, I came to understand that we can’t afford to become too attached to the forms of a tradition. The lineage has carved out a channel so that wisdom can flow through it like a river. The cities built on its banks are the carefully constructed schools of teaching, drawing on its water to fertilize these ideas. But such cities and teaching systems are inhabited only for a while; sooner or later, they decline or are destroyed by others, leaving the river to flow on. Perhaps in time, a new city may be constructed further down its bank.

Why should this be? Why do teaching systems eventually fail? One of the main reasons is that every such school of spirituality (I use the term broadly) eventually becomes a prison. It has locked its adherents into its edifice, and even if it’s more of a palace than a prison, it is a place of captivity. This often occurs when everything has been fully formulated, a point at which the metaphorical architecture of the school has been perfected. At that time it also begins to become obsolete. The best such teaching schools meet the needs of the time, but as those needs are fulfilled and the world moves on, the schools themselves no longer serve the same purpose. “This is inevitable, so every prison must contain within it the seeds of breaking out,” the same teacher told me.

Here, then, is a symbol for the way a spiritual lineage works: there is initial inspiration from wisdom itself, and the person who recognizes this wisdom may channel it so that it flows like a river. Others are drawn to the river and build their edifices on its banks. But in time new constructions will be needed.

Between the decline of one school and the flourishing of the next, however, that river still exists. Further down its course, its wisdom may be recognized by individuals who then start a new initiative to gather others together. Or it may exist in what can be called the “inner planes”—a dimension which cannot easily be traced in history or pinned down chronologically but can sometimes manifest itself directly in the soul of a seeker.

The King on the Mountain

Behind the image of the river and the ruined city, there still lies the question of what gives rise to a particular lineage. Here is a story which indicates how this impulse can come about. It’s a story known as the legend of the King on the Mountain, and it is told in the lineage to which I belong:

There was once a king who wondered what to leave his people. He wanted to leave them something worthwhile, which would endure. He went up the mountain to ponder how best to do that.

“I can construct a beautiful city, or fill a library full of books. That will give them something which endures beyond a lifetime.” But that would not do. He shook his head. “All those things will pass away.”

He reflected further, gazing at the view below of his kingdom spreading out before him. “I could teach them how to improve our agriculture, read the stars more precisely, and develop better weapons for battle. This way the knowledge of how to improve things will be passed down through the generations. Then they can have strength in adversity, and understand how to rebuild when the city crumbles.” The king sighed. “But no. Even that knowledge would become outdated. It would not last.”

Then he found what he had been searching for. “I will leave them the way to knowledge.”

That way to knowledge has come down from that day to this.

And so, according to this story, the king received the wisdom which enabled him to initiate a path of knowledge. To do this, however, he had to strip away all expectations of permanence and grandeur, and of guaranteed outcomes.

This story can be both fascinating and frustrating; in the early days, when I first heard it, it seemed to sweep aside all the new certainties which studying Kabbalah had given me. Learning that we are only a part of the stream of transmission can be hard. But, likewise, a story which is uncomfortable in some ways can also be the grit in the oyster shell. We all tend to hang on to our own version of the truth, which can be very hard-won by our own efforts, so to consider that even this might be transitory is a difficult call. Whether or not this legend has any historical truth to it, it can certainly teach us something about the setting up of a lineage, not just for our lifetimes, but as it can perhaps be perpetuated in different forms over the centuries.

The Eagle and the King

We may never know the full history of a lineage, especially one that is esoteric or has been largely concealed. Such traditions may have been forced underground because of persecution from political or religious systems of the day. From another perspective, some were considered to be appropriate only for true seekers who made the effort to discover them. Trying to pin down the evidence conclusively can therefore be a hopeless aim. But looking into its history can still be fruitful, following up allusions and associations which shed light on its possible transmission.

Pursuing this interest, I followed up on a few leads. I mentioned at the beginning that my teacher would sometimes drop us a few clues about its history; although he himself never claimed to be in full possession of the facts, he had learnt certain things from his own teacher, and discovered others both from his studies and his explorations of the inner worlds. All the clues that I did follow, however unlikely they might seem to start with, turned out to have some foundation. One was a suggestion that our lineage arose about 6,000 years ago in the mountains of Central Asia, at a place not far from what is now Shymkent in Kazakhstan. This in itself is an intriguing proposition, which I have looked into a little in historical terms, but it is beyond the scope of what I can write about in any significant detail in this article. (I hasten to say that this is not one of those stories of hidden Masters in mountain caves who might still be discovered today. It is a historical suggestion, which ties in with the arising of a new phase of ancient civilization, and of the spreading out of peoples over the next few millennia.)

In fact, trade routes running between East and West have played a major part in the transmission of religion, art and culture in general. Such routes developed at least 10,000 years ago. The best-known is the Silk Road, which dates primarily from the first century BC. Actually, the name Silk Road is something of a misnomer, as it was a network of trade routes stretching from East to West, and including branches which ran into India and towards present-day Russia. On all of these routes, travelers and merchants would have swapped stories, passed on ideas, and explained the meaning of their religion.

This potential origin sets the scene for another hint I was given: this lineage may also be connected with the early myths of an eagle-king. Sumerian and Babylonian myths include several involving an eagle who carries a king up into the heavens. The most prominent of these is the tale of King Etana, who heals and befriends a wounded eagle, and then ascends to the heavens on the eagle’s back. The myth also contains the notion of a sacred Tree as a poplar tree in which the eagle builds its nest. It dates from around 2300 BC, and offers a close correspondence with the Kabbalistic ascent of the Tree of Life, which can lead to reunion with the divine world. This strengthens the possible link between myths of the eagle-king and early Kabbalah; there is good evidence that the Kabbalistic Tree of Life did not originate in Judaism, but probably migrated to it from earlier sources in Babylonian culture. (See Parpola. There are also many extant Assyrian and Babylonian carvings and engravings of a stylized Tree of Life glyph, which in some cases looks remarkably like the Extended Tree used today by contemporary Kabbalists.)

The connection between Kabbalah and an eagle-king, or king-eagle, is borne out in at least two other notable stories from later periods. “The Hymn of Robe of Glory” (also known as “The Hymn of the Pearl”) is a Gnostic text from the first or second century CE, which is found in the apocryphal Acts of Thomas. It is a story of exactly this kind, of a return to a heavenly home. The hero is a young man who has been sent to earth to gather a pearl of great price by his royal parents, but he has forgotten that he is a king’s son, that he has a mission to fulfil, and that there is a robe of glory waiting for him back in his true home. As he is now “asleep” in this world, he must be awoken to his real nature. His parents, the king and queen, send an eagle to deliver the message:

It flew in the likeness of an eagle,

The king of all birds;

It flew and alighted beside me,

And became all speech.

At its voice and the sound of its rustling,

I started and arose from my sleep.

I took it up and kissed it,

And loosed its seal (?), (and) read;

And according to what was traced on my heart

Were the words of my letter written.

I remembered that I was a son of kings,

And my free soul longed for its natural state. (Mead, 410; parenthetical comments Mead’s)

I have always found this text moving and very pertinent to the Kabbalistic tradition, with its sense of awakening, recognition, and homecoming.

A later myth known from the medieval period ties the eagle, the king, and the Kabbalah even more closely together. This is recorded in the compilation of Judaic Kabbalistic texts known as The Zohar, and reveals a tradition in which King Solomon—who is of course strongly associated with wisdom—rides on an eagle to ascend to the higher worlds:

[Solomon] ascended unto the roof of his palace, seated himself upon the eagle’s back, and so departed, attended both by fire and cloud. The eagle ascended into the heavens, and wherever he passed the earth below was darkened. The wiser sort in that part of the earth from whence the light was thus suddenly removed would know the cause and would say, “Assuredly that was King Solomon passing by!” (Zohar, 3:334–36)

This was a favorite occupation of Solomon’s, and his goal when he reached the heavens was to discover further secrets: “Solomon, by means of a ring on which God’s name was engraved, would compel the two angels to reveal every mystery he desired to know.” (See Hirsh et al.)

Investigating the legends of lineage brings about not only a sense of connection with the path as it has been traveled over the millennia, but also fresh inspiration for our own journey. It’s well-known that Renaissance art and Baroque music, for instance, were very much inspired by a return to the recently rediscovered Greek philosophical texts. Sometimes digging deeper into the past releases a fresh flow of the water of wisdom.

The act of connecting to lineage may also trigger synchronicities, where inner and outer worlds, past and present, seem to overlap and messages or confirmations are received. A small example of this happened as I was writing this section. I went out for my daily walk, which runs along the tidal river estuary out of our town and around the marshlands at its juncture with another, smaller river. On the pathway, I spotted a barred brown and buff feather, which looks like an eagle’s feather. It isn’t that as such, because we don’t have eagles here in southwestern England. It’s probably from a buzzard, which as a large bird of prey is the closest thing to an eagle in these parts. But I see it as a mysterious and fitting response from the life of the wisdom tradition which I’m exploring. I have brought it back home with me, and it lies on my desk as I write this.

Sources

Hirsh, Emil, et al. “Solomon.” The Jewish Encyclopedia (website), 1906: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13842-solomon.

Mark, Joshua J. “The Myth of Etana,” Ancient History Encyclopedia (website), March 2, 2011: https://www.ancient.eu/article/224/the-myth-of-etana/.

Mead, G.R.S. Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: A Contribution to the Study of the Origins of Christianity. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960 [1900].

Parpola, Simon. “The Assyrian Tree of Life: Tracing the Origins of Jewish Monotheism and Greek Philosophy.” In Journal of Near Eastern Studies 52, no. 3 (July 1993): 161–208.

The Soho Cabbalists (website): https://www.soho-tree.com.

The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. New York: Soncino Press, 1933.

Cherry Gilchrist

Cherry Gilchrist has written a number of books on spiritual and cultural traditions, drawing both from personal experience and extensive research. Recent titles include The Circle of Nine, on feminine archetypes; Tarot Triumphs, an in-depth study of traditional Tarot symbolism; and Russian Magic, on Russian mythology. A newly revised edition of Kabbalah: The Tree of Life Oracle has been launched this year, drawing on a Kabbalistic divination system which she inherited. Cherry lives in Devon, U.K. Her author’s website is at www.cherrygilchrist.co.uk, and her compendium of articles and blogs at www.cherrycache.org.

At New Year’s, I told my wife, “Next New Year’s, we will no longer recognize the world.”

At New Year’s, I told my wife, “Next New Year’s, we will no longer recognize the world.” Don’t let the title of the book

Don’t let the title of the book

I am falling down onto the ground. My arms are turning into front legs. I cry out, “I’m running with the wolves!” I turn completely into a wolf and run off to join my pack. I am filled with such wild exhilaration that I awake with a start and sit straight up in bed. I have no idea what the dream means, but I know that it is special.

I am falling down onto the ground. My arms are turning into front legs. I cry out, “I’m running with the wolves!” I turn completely into a wolf and run off to join my pack. I am filled with such wild exhilaration that I awake with a start and sit straight up in bed. I have no idea what the dream means, but I know that it is special.