Meeting the Needs of the Dying

Printed in the Fall 2016 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Samarel, Nelda, "Meeting the Needs of the Dying" Quest 104.4 (Fall 2016): pg. 114-117

By Nelda Samarel

As with physical needs, it is essential that we understand the emotional, mental, and spiritual needs of the dying individual in order to be of assistance. To understand these needs, expressed or unexpressed, it is helpful to consider what is known of the actual experiences of the dying. Awareness of these will help us to feel more comfortable in their presence and also to communicate more helpfully, making the entire experience less intimidating.

As with physical needs, it is essential that we understand the emotional, mental, and spiritual needs of the dying individual in order to be of assistance. To understand these needs, expressed or unexpressed, it is helpful to consider what is known of the actual experiences of the dying. Awareness of these will help us to feel more comfortable in their presence and also to communicate more helpfully, making the entire experience less intimidating.

Contexts of Awareness

Four basic types, or levels, of awareness are shared by the dying and their loved ones: closed, suspected, mutual pretense, and open (Glaser and Strauss, 2005).

In closed awareness, the person does not recognize that they are dying, although everyone else does. All join in a conspiracy to help keep the secret well-guarded by withholding information that may lead to a realization that death is a prospect. If the person begins to ask questions about their condition, the family may improvise explanations to distract from or explain away new symptoms or developments in the progression of the illness. As the person becomes increasingly ill, the explanations become unconvincing, and the relationships become strained as family and friends be on guard in an effort to protect their secret. Closed awareness causes great tension and is deceitful; everyone is engaged in the conspiracy of silence so that the dying person has no one with whom to speak.

In suspected awareness, the person suspects what others know and attempts to verify the suspicion by luring or tricking family or friends to divulge that information. The person’s suspicion is often aroused by others’ changes in attitudes and behaviors, changes in medical treatment, and noticeable deterioration of condition. In this situation, caregivers usually prefer to allow the dying person to recognize their impending death independently rather communicating it directly. This often results in avoidance of answering direct questions related to the condition. Suspicion usually leads to either mutual pretense or open awareness.

Mutual pretense involves the best known and yet the most subtle of the awareness contexts. Although everyone involved in the situation is aware that the person is dying, all continue to act as if this were not so. The pretense is continued, often with great effort, through a mutual conspiracy of silence fostering an avoidance of death talk. Occasionally the dying person may offer cues signifying that they know they are dying, but loved ones are unwilling to speak the truth. This results in a “let’s pretend” situation in which all are aware of the others’ knowledge, but will not openly admit it and thus keep up the pretense that recovery is possible. Mutual pretense may be useful in giving some dying persons more privacy, dignity, and control. It may, however, result in alienation.

Open awareness exists when the dying person and loved ones know that death is near and acknowledge the fact in their interactions. It affords the opportunity to complete the necessary tasks associated with dying, such as bringing relationships to closure, reflecting on one’s life, and coping with psychological problems such as fears and regrets. Although the open awareness context is preferable to the other three, it may be the most difficult because of the many questions and problems faced by loved ones. For example, they need to decide whether the dying person should be made aware of all facets of the situation, including the details of the prognosis. Would such knowledge cause depression or, possibly, suicide?

It is helpful to understand the awareness context in which an interaction takes place, because all talk and action are guided by what one knows. Although a shift toward open contexts of awareness is usually encouraged, it is not always possible or desirable to maintain an entirely open awareness. Some dying persons, or their loved ones, may not be prepared to function with open awareness because of high anxiety, limited communication ability, or a tendency toward denial. Denial, in fact, may be healthy and necessary for many individuals. What is most important is not to impose a particular context of awareness on another, remembering that every individual has developed different coping skills and views death differently.

The Trajectory of Dying

Dying may be considered a process that occurs over time. As such, it may take a variety of forms, or trajectories (see Glaser and Strauss, 2007, and Benoliel). All trajectories take time and have a certain shape through time. For example, the trajectory may plunge straight downward; move slowly and steadily downward; vacillate slowly, moving slightly up and down before plunging downward; or move downward, reach a plateau and hold, then plunge rapidly downward toward death.

The duration of the dying trajectory may be either lingering, expected quick, or unexpected quick. The varying factors of certainty and time yield four types of trajectories: (1) certain death at a known time (e.g., late-diagnosed metastatic cancers); (2) certain death at an unknown time (e.g., chronic fatal illness, such as chronic kidney failure); (3) uncertain death, with a known time when certainty will be established (e.g., radical surgery for cancer, where a successful outcome may be known, but the threat of recurrence may be continually present); and (4) uncertain death at an unknown time (e.g., multiple sclerosis or other chronic diseases of uncertain outcome).

It is important to recognize that these dying trajectories are subjective rather than actual courses of dying and may, in fact, be inaccurate.

Uniqueness of the Personal Experience

There is the notion of an appropriate death: a style of dying that is adapted to each specific person. Respect for each individual’s personality and values defines what may be appropriate for that person. Each must live his own life and death in a manner consonant with his own pattern of living and dying, his definitions of life and death, and within his own context. Thus an appropriate death is different for each individual.

It is imperative to understand the ways in which dying individuals have lived through and experienced previous stressful life events in order to understand how they respond to the challenges of the dying process. How individuals have behaved during earlier life crises will give significant clues to how they will behave during dying. In other words, people die in the same way that they live. The situation—dying—may be extraordinary, but variables such as personality traits and coping history remain long-established and will result in similar styles of dealing with the challenges of dying.

Stages of Dying

Five stages that refer to the person’s successive mental and emotional responses to dying have been identified: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (Kübler-Ross).

Denial (“No, not me”), the first response, is an attempt to negate or escape from the idea of one’s own death. Most individuals experience partial and temporary denial. It is a form of natural protection and allows us to manage fear. To provide support for persons who are in denial, it is helpful to invite them to talk about their fears, but without attempting to force them out of denial.

The second stage, anger (“Why me?”), often characterized by envy, rage, and resentment, is often difficult for family members, who may be the target of the anger. This stage is stimulated by fear and frustration. Understanding that anger is a normal response to a terminal illness can help keep outbursts in perspective and accept this behavior as temporary and normal.

In bargaining (“Yes, me, but . . .”), the third stage, the dying person attempts to forestall the inevitable by making a deal with the doctor, family, God, or fate if he or she is permitted to live somewhat longer. At this point, the person recognizes the prognosis but is still attempting to modify the outcome. Sincere listening and realistic support can be offered.

Depression (“Yes, me”; grieving) is associated with the ultimate future loss of life and may be characterized by fatigue, loss of function, feelings of guilt, and fear of dying. The dying person realizes that bargaining is of no use and becomes sorrowful and withdrawn. Simply being present and accepting when a person is depressed is more helpful than attempting to talk them out of their depression or to distract them.

The final stage, acceptance (“Yes, me”), signifies the end of the struggle. It is not always accompanied by a happy or serene feeling. In fact it is often associated with an absence of all feeling.

These stages are not rigid, nor are they mutually exclusive. Moreover, hope tends to persist in all stages, even depression and acceptance. Indeed it is asserted that, without hope, death follows shortly (Kübler-Ross).

Although many dying individuals do experience these stages in clearly observable ways, they will not necessarily move through the five stages in a linear fashion or experience all stages.

Factors Influencing the Dying Process

Several factors influence the experience of dying: age, gender, the nature of the disease and environment, and religion and culture.

Chronological age affects the way in which dying and death are comprehended, since the intellectual grasp of death is related to the individual’s developmental level and extent of life experiences. Accordingly, the experience of a mature adult will differ considerably from that of a young child, who may not comprehend the nature of death.

One example clearly illustrates the influence of age on the experience of dying. A young child with a diagnosis of terminal cancer and a life expectancy of less than six months began to question her future when the pain from her bone cancer interfered with her ability to walk. She struggled to understand the concept of death but could not easily move beyond the fear of being alone, that is, without her parents. Her major concern was who would take care of her.

Age further influences the dying process, because children and adults have different opportunities to exercise control over the situation. The same young child mentioned above understandably had little opportunity to participate in the decision making process regarding her treatment, and attempted to control the situation in other ways. For example, she would refuse to respond to adult conversation at times, indicating that she would be the one to decide when and if conversation would be initiated, emphatically declaring in response to a statement or question, “Not now! We’ll talk after the cuckoo (clock) strikes!” Age also influences the perceptions of others and the ways in which one is treated. Although this child clearly was in the terminal phase of cancer, the treatment team found it difficult, if not impossible, to make the final decision to terminate treatment, as is often the case when treating young children. In cultures where youth is greatly valued, it is often difficult to become reconciled to the untimely death of a child. Conversely, advancing age may result, not always appropriately, in a less aggressive treatment protocol.

Gender affects the dying experience because of the difference in life roles for men and women and the resulting difference in values. For example, a man who is facing a life-threatening illness may be more concerned with financial provisions for his family, while a woman may be more concerned with family integrity and caregiving (“Who will cook for my husband?”).

Disease, treatment, and environment critically influence the experience of dying. Each individual dies of a particular cause in a particular place. For example, a lung condition associated with breathing difficulty and with being treated in a hospital is likely to cause more alarming symptoms than is a home death due to chronic kidney failure, where one may simply become increasingly lethargic as death approaches.

Attitudes and beliefs about life, living, and death, as shaped by religion and culture, influence the dying process. For example, a person who believes that death signifies the end of all life may fear death. Conversely, a person who believes in an afterlife or in reincarnation may fear the anticipated separation from loved ones, but not the dying process or death itself. The profoundly different nature of these two individuals’ fears will influence how they respond to the process and the ways in which loved ones can assist them through it. One way of initiating conversation about the dying person’s beliefs about an afterlife is simply to ask, “What do you believe happens afterwards?”

Having a faith, too, influences the experience of dying. One hospice nurse said, “At the end, those with a faith—it really doesn’t matter in what, but a faith in something—find it easier. Not always, but as a rule. I’ve seen people with faith panic, and I’ve seen those without faith accept it [death]. But, as a rule, it’s much easier [for those] with faith” (Samarel, 64–65).

Words from Those Nearing Death

Persons nearing death quite often will speak, within their own frames of reference, of preparation for travel. For example, the businessman may fret about needing to find his passport, while the sailboat buff may ask about the tides. The recurrence of this theme is consistent with the concept of death as a passage or journey. Often the dying person has a sense of being accompanied by another who already has died. Most often, the dying recognize a deceased relative or close friend; occasionally they speak of angels or religious figures.

In one beautiful situation, an elderly dying woman was seen by her adult granddaughter to be conversing with her long-dead husband. Following this “conversation,” she told her granddaughter with great serenity that Grandpa had stopped by to tell Grandma not to be afraid and that she would be joining him soon. He also said that he would be guiding her on her journey among beautiful gardens. She shortly drifted off to sleep, her face tranquil and calm; she died a short while later.

One imminently terminal man, asleep in his hospital room, awoke with a start, became quite alert and called the nurse to his bedside. He said that, while asleep, he had seen two angels who would be with him when he was ready “to go.” Several days later he serenely pointed to a corner of the ceiling and announced in a matter-of-fact manner, “There they are, the angels. They’ve come for me.” He then took one final breath and closed his eyes. The messages here are that dying persons are not alone and may, in fact, be blessed with help in a form unique to them.

SOURCES

Benoliel, Jeanne Quint. “Health Care Providers and Dying Patients: Critical Issues in Terminal Care,” in Omega 18, 1987–88.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss, Awareness of Dying. New Brunswick, N.J.: Aldine Transaction, 2005.

———.Time for Dying. New Brunswick, N.J.: Aldine Transaction, 2007.

Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy, and Their Own Families. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Samarel, Nelda. Caring for Life and Death. Washington, D.C.: Taylor & Francis, 1991.

Nelda Samarel, Ed.D., R.N., a longtime student of the Ageless Wisdom, has been director of the Krotona School of Theosophy and a director of the Theosophical Society in America. She serves on the executive board of the Inter-American Theosophical Federation. A retired professor of nursing, Dr. Samarel has numerous publications and presents internationally. Her article “A Visit to John of God” appeared in the summer 2016 issue of Quest.

This article is excerpted from Samarel’s booklet Helping the Dying: A Guide for Families and Friends Assisting Those in Transition, published by the Theosophical Order of Service. For a free copy, please write to: Theosophical Society in America, Attention: Helping the Dying, P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60187-0270, or to helpingthedying@hotmail.com.

National secretary David Bruce reminds me that this year is the 400th anniversary of the death of Shakespeare. Which raises a question: what exactly was Shakespeare’s worldview?

National secretary David Bruce reminds me that this year is the 400th anniversary of the death of Shakespeare. Which raises a question: what exactly was Shakespeare’s worldview? The call came at 2:15 a.m. It was my first on-call summons since I had become a hospice nurse a month earlier. I dressed quickly, running a comb through my sleep-flattened hair, feeling more than a little as firemen do as they jump into their boots and slide down the pole when the alarm sounds. I reviewed the patient’s name and address and the message the triage nurse had given me on the phone: “Madeline D. is close to dying. Her family is expecting you as soon as you can get there.” On the way, I carefully remembered what I had been taught to do when I arrived. My heart would tell me what to say.

The call came at 2:15 a.m. It was my first on-call summons since I had become a hospice nurse a month earlier. I dressed quickly, running a comb through my sleep-flattened hair, feeling more than a little as firemen do as they jump into their boots and slide down the pole when the alarm sounds. I reviewed the patient’s name and address and the message the triage nurse had given me on the phone: “Madeline D. is close to dying. Her family is expecting you as soon as you can get there.” On the way, I carefully remembered what I had been taught to do when I arrived. My heart would tell me what to say. For many years I believed that retirement was only a sad commentary on the unpleasantness of most work. After all, if work is an unpleasant necessity and to be avoided, as it is for many, then why not seek relief at every opportunity? Weekends are to the work week as vacation is to the year, as retirement is to a life’s work. The assumption is that leisure is what’s enjoyable and work is the price one pays to get it. The solution, of course, is to have not just a job but a satisfying life’s work, thereby blurring the distinction between work and nonwork.

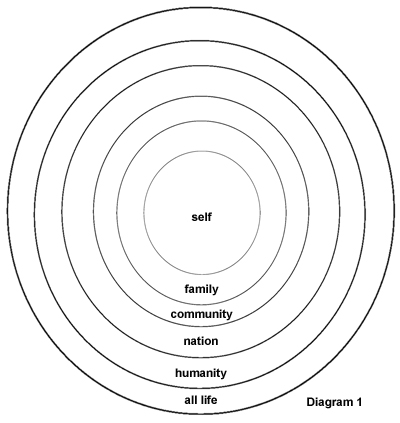

For many years I believed that retirement was only a sad commentary on the unpleasantness of most work. After all, if work is an unpleasant necessity and to be avoided, as it is for many, then why not seek relief at every opportunity? Weekends are to the work week as vacation is to the year, as retirement is to a life’s work. The assumption is that leisure is what’s enjoyable and work is the price one pays to get it. The solution, of course, is to have not just a job but a satisfying life’s work, thereby blurring the distinction between work and nonwork. We can begin by assuming that the wider the perspective an individual has, the more mature, and therefore the more awake, she is. Consider the accompanying diagram, which roughly depicts the stages of human cognitive growth. The child begins by becoming aware of self, then of family, community, nation, the whole of humanity, and possibly even all sentient life.

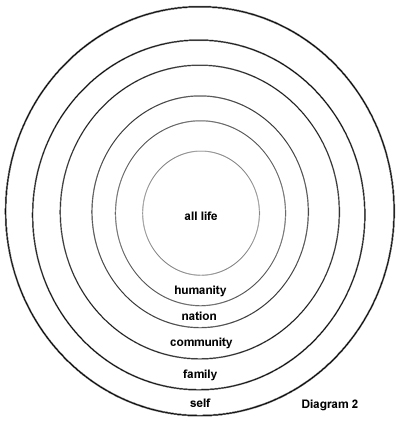

We can begin by assuming that the wider the perspective an individual has, the more mature, and therefore the more awake, she is. Consider the accompanying diagram, which roughly depicts the stages of human cognitive growth. The child begins by becoming aware of self, then of family, community, nation, the whole of humanity, and possibly even all sentient life. At the beginning of this article, I said that diagram 1 was crude and arbitrary. Diagrams are always treacherous. They oversimplify and distort; they conceal as much as they illumine. Thus we may learn something by turning it inside out (diagram 2).

At the beginning of this article, I said that diagram 1 was crude and arbitrary. Diagrams are always treacherous. They oversimplify and distort; they conceal as much as they illumine. Thus we may learn something by turning it inside out (diagram 2).