Printed in the Spring 2017 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Leland, Kurt,"The Rainbow Body: How the Western Chakra System Came to Be" Quest 105.2 (Spring 2017): pg. 25-29

By Kurt Leland

On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.

On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.

These medallions were representations of the seven chakras (Sanskrit for “wheels”), a schema that originated centuries ago in India in connection with a type of yoga that has become a staple of contemporary yoga classes and New Age metaphysics. The chakras are said to appear to clairvoyant vision as whirling disks or vortices of light, hence their name. Ancient texts taught that their activation through strenuous meditative and ritual practice would result in a seven-step process of consciousness expansion leading to enhanced spiritual powers, enlightenment, and liberation from the karmic law of rebirth.

The product in the brochure was called “Organic Chakra Balancing Aromatherapy Roll-Ons.” It was made by Aura Cacia, an American company that markets scented essential oils manufactured from herbs and flowers for healing purposes—hence aromatherapy. The brochure opened into a vertical table of color-coded correspondences identifying the locations, qualities, and effects on emotion, mind, and spirit of chakras that have been “balanced” through the use of these aromatherapy roll-ons—one for each chakra, each compounded of a different formula of essential oils.

Several half-amused questions came to mind: Could a scent really “open the floodgates of compassion and understanding” associated with the heart chakra? Why was the “empowering” third chakra associated with a “delicate citrus blend”? How would a fully enlightened being smell when wearing all seven scents at once?

The predominant question was, how did we get here from there? The list of chakra qualities was familiar from dozens of New Age books on the subject: grounding in the first chakra, sensuality or sexuality in the second, empowerment in the third, compassion in the fourth, communication in the fifth, intuitive insight in the sixth, and enlightenment in the seventh. Yet anyone who looks into the origins of the chakra system in India may be astonished to find that the chakras have colors, but there is no rainbow; they have qualities and spiritual powers, but not those on this list. No scents are involved. The idea of chakra balancing is never mentioned in the scriptures. The chakras are to be pierced, dissolved, and transcended to achieve a state of “liberation within life” rather than an emotionally and spiritually balanced lifestyle (whatever that might mean).

I first heard of the chakras in the late 1970s from a friend who was a disciple of an Indian yogi. I learned their locations and how to breathe to purify them. Through the metaphysical grapevine, I learned of a list of chakra qualities similar to the one in the Aura Cacia brochure. A few books on the subject were available in metaphysical bookstores, but I did not buy or read them.

Fast forward to 2002. I was asked to write a book on the spiritual effects of music. I considered using the chakra system as a framework for describing mystical or peak experiences associated with composing, performing, and listening to music. Dozens of books on the chakras were now available, with many variations in listing the colors and qualities. I wanted to work with the most authentic list of qualities I could find. But research into ancient Indian systems confused me—some had as few as four chakras, and others as many as forty-nine. Several questions drove me, though they were still unresolved when the book was published in 2005:

When did the term chakra first come into the English language?

When did the rainbow color scheme originate, and who was responsible for it?

Where did the ubiquitous New Age list of chakra qualities come from, and how long has it been around?

In the summer of 2012, Quest Books, a publishing imprint of the Theosophical Society in America, approached me about annotating a new edition of The Chakras, published in 1927 by Charles W. Leadbeater, a clairvoyant who worked within the TS. This book had been in print continuously for nearly ninety years. Though considered a classic in the field of New Age chakra studies, it was not an easy read. Leadbeater used obscure terminology, assuming his Theosophical readership would understand it without explanation. Furthermore, there were several ways in which his clairvoyant perceptions of the chakras differed not only from ancient Indian texts, but also from recent New Age books. I tried to create an “authoritative,” stand-alone text, with notes explaining all the terms and an afterword that placed the book in context within the evolution of the New Age version of the chakra system.

This project allowed me to solve the problem of where the rainbow color scheme came from. Being under a tight deadline, I was unable to pursue the other questions. However, in the summer of 2014, I received a request to give a talk on the chakra system at the Theosophical Society in Milwaukee later that year. That opportunity allowed me to further my research. I was able to trace the first references to the chakra system in English. I was also able to track the century-long evolution of what I call the Western chakra system. This evolution began in the 1880s, in the writings of H.P. Blavatsky, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society, and was more or less complete by 1990, when actress Shirley MacLaine appeared on the Tonight Show and amused a TV audience of millions by affixing colored circles representing the chakra system onto talk-show host Johnny Carson’s clothing and head. I have concluded that the evolution of the Western chakra system was an unintentional collaboration among the following:

• Esotericists and clairvoyants (many with a Theosophical background)

• Scholars of Indology (the study of Indian culture, including religious beliefs)

• Mythologist Joseph Campbell

• Psychologists (Carl Jung and the originators of the human potential movement at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California)

• Indian yogis (some of whose “ancient” teachings made use of Leadbeater’s color system)

• Energy healers (Barbara Brennan, author of Hands of Light, a best-selling manual of energy healing, and others)

Surprisingly, the two primary strands of this evolutionary sequence—the rainbow color scheme and the list of qualities—did not come together in print until 1977. Thus the much-vaunted “ancient” chakra system of the West is barely forty years old, its history obscured by the habit of New Age writers, both in print and on the Internet, of failing to include notes and sources for their information—a habit that Olav Hammer, a Swedish professor of the history of religion, calls

I wrote Rainbow Body: A History of the Western Chakra System from Blavatsky to Brennan for people who want to know about the real history of the Western chakra system—a wild and wacky story that somehow produced a body of spiritual and alternative healing practices that have profoundly influenced the lives of millions. But what is the Western chakra system? To my knowledge, the term has not previously been used, except informally, to differentiate versions of the chakras evolved in metaphysical circles in the West from their Hindu forebears. Here are the salient features, listed in the chronological order in which the Western chakra system’s components were recognized, schematized, and adopted:

• A seven-chakra base (1880s)

• Association of each chakra with a nerve plexus (1880s)

• A list of vernacular (non-Sanskrit) names (1920s)

• Association of each chakra with a gland of the endocrine system, with minor variations from system to system, especially with regard to the pituitary and pineal glands (1920s)

• Single colors attributed to each chakra in order of the spectrum—either seven colors, including indigo, or six colors plus white (1930s)

• An evolutionary scale of psychological and spiritual attributes, functions, or qualities assigned to each chakra, eventually becoming the familiar single-word list given earlier

To this listing may be added a number of less common attributes (in alphabetical order):

• Associations with layers of the aura, subtle bodies, and planes

• Developmental stages in the evolution of humanity

• Developmental stages in the evolution of the individual

• Diseases of mind or body associated with each chakra

• Elements (earth, water, fire, air, and ether)

• Positive and negative emotions for each chakra

• States of consciousness and psychic powers

Beyond these categories, there is an endless number of correspondences based on Western esotericism or alternative healing practices, including but not limited to the following:

• Alchemical metals

• Astrological signs and planets

• Foods and herbs

• Gemstones and minerals

• Homeopathic remedies

• Kabbalistic sefirot (“spheres” or “principles” pertaining to various aspects of creation)

• Musical notes

• Shamanistic totem animals

• Tarot cards

| |

|

| |

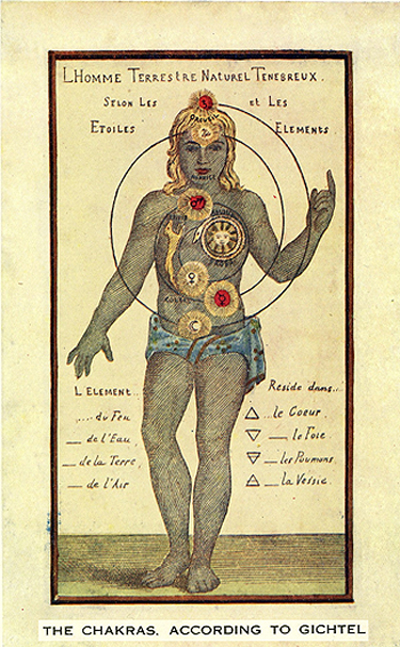

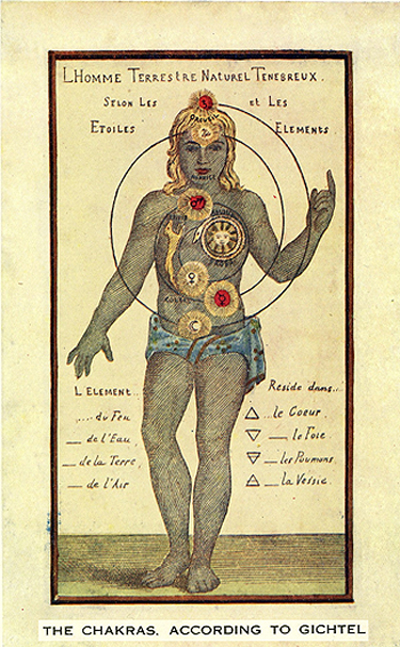

This diagram is taken from a nineteenth-century French translation of Johann Georg Gichtel’s Theosophia practica (1701), as reproduced in C.W. Leadbeater’s book The Chakras. Entitled “The Dark, Natural, Terrestrial Human according to the Stars and the Elements.” It shows a possible forerunner of the Western chakra system. The planets and elements, and some of the deadly sins, are connected with certain human centers (e.g., Saturn, at the crown, with orgueil, “pride”; Jupiter, in the forehead, with avarice). The text on the bottom half of the chart reads: “The element of fire resides in the heart; the element of water, in the liver; earth, in the lungs; and air, in the bladder.” |

To make sense of how the Western chakra system evolved, I had to deal with the early evolution of the system in India, from the first to the sixteenth century CE. Then I had to trace the movement of this Eastern chakra system to the West. It turns out that Mme. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society played a key role in transmitting these teachings from 1879, when she arrived in India, until her death in 1891. Blavatsky and subsequent generations of Theosophical clairvoyants, including Leadbeater, Annie Besant, Rudolf Steiner, and Alice Bailey, significantly altered these ancient teachings.

During the fifty years from Blavatsky’s arrival in India to the publication of Leadbeater’s The Chakras, several components of the Western chakra system fell into place: the seven-chakra base, the locations in association with nerve plexuses, and the non-Sanskrit names. From the 1920s to the 1950s, the Western chakra system gradually acquired its association with the rainbow colors and the endocrine glands. The key players during this period were not only well-known psychics, such as Alice Bailey and Edgar Cayce, but also several who are mostly unknown: Ivah Bergh Whitten, an early color therapist working in the United States (her teachings were disseminated through the writings of her primary student, Roland Hunt, author of The Seven Keys of Color Healing, a standard manual for over forty years); S.G.J. Ouseley, a British color therapist; and the mysterious American yogini Cajzoran Ali. The latter was born in Iowa under the name Amber Steen, got married to a dark-skinned Indian swami who turned out to be a confidence man from Trinidad, and worked as a yoga teacher in the United States and France under numerous aliases. Though she was the first to bring the chakra system and the endocrine glands together in a book published in 1928, her previously untold story, as these details suggest, turns out to be the wackiest of all.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, a parallel strand of development in the Western chakra system involved German Indologists Heinrich Zimmer and Frederic Spiegelberg (both had been forced out of Nazi Germany and worked in American universities), the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, and the American mythologist Joseph Campbell. Each interacted with the others under the inspiration of The Serpent Power, a book published in 1919 by an Indian High Court judge, Sir John Woodroffe, using the pseudonym Arthur Avalon. Woodroffe’s was the first scholarly publication in English of one version of the Western chakra system—the same one that influenced Blavatsky when she became aware of it forty years before.

Zimmer inspired Campbell to investigate the chakra teachings of the late nineteenth-century Indian saint Sri Ramakrishna. Spiegelberg inspired Michael Murphy, the founder of Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, to investigate those of the early twentieth-century yoga master Sri Aurobindo. Esalen produced the human potential movement, a loose-knit band of psychologists, philosophers, and bodyworkers, including Abraham Maslow and Ram Dass. This movement was an important influence on the hippie counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

It was at Esalen that the list of chakra qualities with which we are now familiar emerged from a fusion of Ramakrishna’s and Aurobindo’s teachings. Furthermore, Ken Dychtwald, one of the bodyworkers who lived at Esalen during this time, became the father of the Western chakra system when he inadvertently brought together the color healers’ list of rainbow colors and endocrine glands and the human potential movement’s list of chakra qualities in a book and article published in the summer of 1977. The book, Bodymind: A Synthesis of Eastern and Western Approaches to Self-Awareness, Health, and Personal Growth, was published in June 1977, and a related article, “Bodymind and the Evolution to Cosmic Consciousness,” was published in the July-August 1977 issue of Yoga Journal. That article contains a list of chakra qualities very similar to the one I saw in the Aura Cacia brochure four decades later. Thus 2017 represents the fortieth anniversary of the birth of the Western chakra system, reverently referred to in yoga classes and New Age books as “ancient.”

In the 1980s, writers such as Anodea Judith (Wheels of Life) began consolidating information from various chakra systems to resolve such controversies and reinforce the hegemony of the system we now consider traditional. This was also the decade when innovative practitioners in the developing field of energy medicine began applying the chakra system to various forms of bodywork, including acupuncture, Polarity Therapy, and Reiki. Toward the end of the decade, best-selling author and actress Shirley MacLaine was offering public workshops on the chakras—and her October 4, 1990, appearance on the Tonight Show could be called the Western chakra system’s coming-out party. It was no longer an esoteric yoga teaching but an aspect of popular culture.

In the 1990s, books, workshops, websites, and music based on the chakras proliferated, touching on many forms of spiritual and healing practice—though often repeating what had gone before. However, there was one further, ongoing stage in the development of the Western chakra system: the codifying of esoteric teachings on chakras, subtle bodies, and planes and their use in astral projection. Speculations on such topics accompanied the development of the Western chakra system like a shadowy secondary rainbow during much of the twentieth century and emerged into their clearest presentation in the energy healing work of Barbara Brennan. Her immensely popular book Hands of Light, which correlates the chakras with seven subtle bodies, planes, and layers of the human aura, was first published in 1988 and remains in print today.

Contemporary historians of South Asian religions who specialize in fields in which the chakras play a part sometimes rail against Western New Age appropriation of these teachings. Nevertheless, the unintentional collaboration of esotericists, clairvoyants, scholars, psychologists, yogis, and energy healers that produced the Western chakra system probably mirrors the spread of Tantric teachings throughout East Asia over many centuries. In both cases, a constant selection and recombination of details determined what was left out and what was passed on. If that spreading fulfilled ancient cultural and spiritual needs, the same thing could be said of the modern West—even if the result has been commodified in ways unimaginable in the India of a thousand years ago (as in the case of aromatherapy roll-ons).

I see the development of the Western chakra system as the embodiment of a deeply meaningful archetype of enlightenment, common to East and West—that of the spiritually perfected being, graphically represented by the image seen so often on covers of books on the chakras: a resplendent, meditating human form, shining with the rainbow-colored light of having fully realized our spiritual potential, each chakra representing an evolutionary stage on this sacred developmental journey.

Composer and author Kurt Leland lectures regularly for the TSA. His books include a compilation of Annie Besant’s articles: Invisible Worlds: Essays on Psychic and Spiritual Development (Quest Books, 2013). This article, which originally appeared in New Dawn magazine, is adapted from his latest book, Rainbow Body: A History of the Western Chakra System from Blavatsky to Brennan (Ibis, 2016). His consulting practice, Spiritual Orienteering, is based in Boston. He can be reached at www.kurtleland.com. Videos of his lectures can be found on the TS YouTube channel.

At the time of this writing, we have just finished the 141st annual convention of the international Theosophical Society. Again this year it was held at the headquarters in Adyar. Year after year, this event is the largest purely Theosophical gathering in the world, with over 1000 people attending. Members from around the world and from every corner of India make their plans and adjust their schedules so that they can participate. The convention lasts for five days, and during the course of the event you meet people who have a long history with the TS. It is not uncommon to encounter members who have attended every convention for the past fifty, and in some cases sixty, years. Their memories of the past and observations about the present are priceless.

At the time of this writing, we have just finished the 141st annual convention of the international Theosophical Society. Again this year it was held at the headquarters in Adyar. Year after year, this event is the largest purely Theosophical gathering in the world, with over 1000 people attending. Members from around the world and from every corner of India make their plans and adjust their schedules so that they can participate. The convention lasts for five days, and during the course of the event you meet people who have a long history with the TS. It is not uncommon to encounter members who have attended every convention for the past fifty, and in some cases sixty, years. Their memories of the past and observations about the present are priceless. On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.

On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.