Printed in the Winter 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Keene, Douglas, "A Brief Introduction to Theosophy" Quest 113:1, pg 25-30

By Douglas Keene

The whole order of nature evinces a progressive march toward a higher life.

―H.P. Blavatsky

“It was once said of the Christian Scriptures,” wrote early Theosophist Annie Besant, “that they contained shallows in which a child could wade and depths in which a giant must swim.” Theosophy is similar, she went on, “for some of its teachings are so simple and so practical that any person of average intelligence can understand and follow them, while others are so lofty, so profound, that the ablest strains his intellect to contain them and sinks exhausted in the effort” (Besant, Ancient Wisdom, 1).

Besant, who became the second president of the international Theosophical Society in 1907, was speaking over a century ago. And even now, when members of the Society are asked, “What is Theosophy, anyway?” they have difficulty responding with a short and simple explanation.

Indeed, many search for years trying to find the true nature of Theosophy. Theosophical thought and commentary spanning numerous topics and perspectives fill libraries (as just one example, approximately 28,000 books, periodicals, and video and audio recordings are housed at the U.S. national headquarters in Wheaton, Illinois). The scope of Theosophy is broad, the depths layered, and the content inexhaustible. It has been called a religion, a philosophy, and a spiritual movement based on the Ancient Wisdom. None of these descriptions suffice to encompass the complexity of the subject, as both students and swimming giants know.

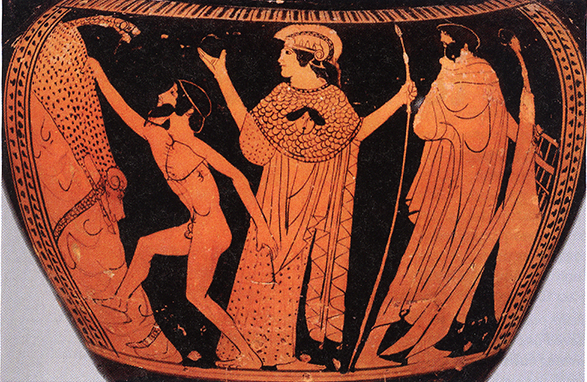

The modern Theosophical Society was founded in 1875 in New York City by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge, and a small number of other students. The term theosophy, however, goes much further back in time, and its core concepts even further. Theosophia, a Greek term combining theos (god) and sophia (wisdom), is often defined as divine wisdom, wisdom of the gods, or knowledge of divine things (the word first appears in the writings of Neoplatonists in the third century AD). Theosophical views have been endorsed by Rosicrucians and Freemasons as well as taught in ancient mystery schools and secret societies in Egypt, Chaldea, and other locations. Adding to potential confusion, many philosophical organizations today—including branches of the original society founded in New York, as well as nonassociated groups and organizations such as Freemasonry, Anthroposophy, and New Age movements—use the term. In The Key to Theosophy, as the fictitious Enquirer asks, “What is the real meaning of the term?” Mme. Blavatsky’s reply is illuminating:

“Divine Wisdom,” (Theosophia) or Wisdom of the gods, as (theogonia), genealogy of the gods. The word theos means a god in Greek, one of the divine beings, certainly not “God” in the sense attached in our day to the term. Therefore, it is not “Wisdom of God,” as translated by some, but Divine Wisdom such as that possessed by the gods. The term is many thousand years old.

She noted that the term comes to us from the Alexandrian philosophers and “dates from the third century of our era and began with Ammonius Saccas and his disciples” (Key to Theosophy, 1‒2). The term has been used in Greek and Latin writings, particularly in those of Neoplatonism, who bear the influence of Ammonius.

HPB once described Theosophy as “the shoreless ocean of universal truth, love, and wisdom, reflecting its radiance on the earth, while the Theosophical Society is only a visible bubble on that reflection” (Key to Theosophy, 57).

Mme. Blavatsky published her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine, in 1888. Its subtitle―The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy―is perhaps a useful way to regard Theosophy as a whole.

Theosophy is a science in the sense that it can explain our natural world in many ways that have been mysterious to conventional science but are often later confirmed by discoveries such as Blavatsky’s apparent foreknowledge of the wave/particle duality of light (Carlson). It goes much further than mere physical manifestation in describing many layers of “superphysical” existence on higher planes, each with a delicate balance of spirit and matter. Natural laws apply as well to these higher planes, but they are largely uninvestigated by today’s scientists. People with clairvoyant ability have in some cases studied these realms. As Leadbeater describes this advantage,

It asserts that man has no need to trust to blind faith, because he has within him latent powers which, when aroused, enable him to see and examine for himself, and it proceeds to prove its case by showing how those powers may be awakened. It is itself a result of the awakening of such powers by men, for the teachings which it puts before us are founded upon direct observations made in the past, and rendered possible only by such development. (Leadbeater, 2)

Theosophy is a religion in the sense that many of its tenets are incorporated in today’s religious beliefs, particularly at the esoteric level. Mme. Blavatsky used the term wisdom-religion and describes it thus:

It is from this WISDOM-RELIGION that all the various individual “Religions” (erroneously so-called) have sprung, forming in their turn off-shoots and branches, and also all the minor creeds, based upon and always originated through some personal experience in psychology. Every such religion, or religious offshoot, be it considered orthodox or heretical, wise or foolish, started originally as a clear and unadulterated stream from the Mother-Source. The fact that each became in time polluted with purely human speculations and even inventions, due to interested motives, does not prevent any from having been pure in its early beginnings. (Blavatsky, Collected Writings, 10:167)

This quotation shows the jaundiced eye and sharp tongue HPB had for human distortion of divine teachings. The motto of the Theosophical Society is “There is no religion higher than truth.”

The philosophy of Theosophy, often termed esoteric (hidden) philosophy, refers to a body of knowledge about the cosmos, the Divine, and the human being that takes into account not only the visible aspect but more predominantly the invisible, metaphysical, and spiritual dimensions. HPB notes that “Esoteric philosophy, teaching an objective Idealism―though it regards the objective Universe and all in it as Māyā, temporary illusion―draws a practical distinction between collective illusion, Mahāmāyā, from the purely metaphysical standpoint, and the objective relations in it between various conscious Egos so long as this Illusion lasts” (Blavatsky, Secret Doctrine 1:631).

This esoteric knowledge is protected to a degree in that it is understandable and accessible fully only to those who are dedicated to the search and who, through a series of initiations, can come to a perfected state of awareness and insight.

The present mission statement crafted by the international Theosophical Society in 2018 reads as follows: “To serve humanity by cultivating an ever-deepening understanding and realization of the Ageless Wisdom, spiritual self-transformation, and the unity of all life.”

It appears self-evident that this Ancient Wisdom cannot be communicated in a few words (or even ten thousand). Borrowing from the Sanskrit words, jnana (knowledge) may be a beginning but cannot take us the entire route. Bhakti (devotion) is also necessary. Karma (service and altruism) is a sine qua non. Now it is becoming more obvious why Theosophy is difficult to define.

At the time of the founding, Three Objects were established that are core to the teachings of Theosophy. These have been essentially unchanged since that time and presently are listed as follows:

1. To form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or color.

2. To encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

3. To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity.

Regarding the First Object, to form a “brotherhood of humanity”: brotherhood, of course, was presented as a nongender term for the unity, compassion, and mutual service of the human race. It is predicated on the belief that all beings―in fact, all manifested (and unmanifested) matter―are interconnected and an aspect of a universal whole. This object is to form a “nucleus” of those who are aware of this unity and can model and share it with those who are not yet able to see. Despite the illusion, we are not separate beings, and any action to help or harm another, in truth helps or harms us as well.

The Second Object―to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science―is critical for having a deeper understanding of past and present approaches to our natural world and for being conversant in central belief structures; it also shows a respect and appreciation for contributions of other individuals and organizations, small and large. Only by understanding our roots in these disciplines can we hope to integrate the highest aspects into our own comprehension and have a yardstick against which we may judge new notions and ideas. Additionally, pursuing this object will provide unity among different traditions, emphasizing similarities over differences and perhaps finding that at their essence all pursuits have a harmonious relationship.

Finally, regarding the Third Object, which addresses the “unexplained laws of nature” and the “powers latent in humanity,” there appear to be powers in the universe unknown to us and abilities in individuals that are difficult to explain. This confusion is in part due to our myopic views of nature, which are confined primarily to the physical plane and distorted through habituation and training. Nevertheless, we hear stories daily about telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, psychokinesis, and other paranormal phenomena. Descriptions abound of near-death experiences, and many books are written on the subject annually. Do we really know who and what we are? What are the depths of human existence and consciousness, and how can we attain them? These profound questions have engaged the human mind from time immemorial. We are encouraged to “investigate” and look for answers. In some sense, Theosophy helps point the way.

Theosophy teaches that the human being consists not of a single body but in fact seven, superimposed on each other at different vibrational frequencies. All manifestation, in fact, is of a septenary nature. These layers of being are often called seven “principles.” They have different names and are sometimes categorized differently, but generally they are divided into the lower four (the lower quaternary), consisting of the physical body, vitality, the astral body (or etheric double), and the emotional body—all of which are mortal and sequentially perish—and the higher three (upper triad), which are immortal. This triad comprises the higher mind (Sanskrit manas), the intuition (Sanskrit buddhi), and the spirit (Sanskrit atma). The common conception that human beings are a body and have a soul is reversed: the Theosophical belief is that human beings are a soul and have a body. Our physical form is simply a vehicle, a collection of attributes and characteristics, manifested in a specific time and place, that carry our eternal being. Therefore, death is merely a temporary transition to another form and eventually to another body. Leadbeater notes:

What is called death is the laying aside of the vehicle belonging to this lowest world, but the soul or real man in a higher world is no more changed or affected by this than the physical man is changed or affected when he removes his overcoat. All this is a matter, not of speculation, but of observation and experiment. (Leadbeater, 3)

This line of thought leads to the linked concepts of reincarnation and karma. A human lifetime truly is just a day in the eternal life of the real self, the soul. Theosophical sages such as the Mahatmas, Blavatsky, Besant, and Leadbeater tell us that we have experienced numerous past lives, perhaps hundreds or even thousands, and will experience many more in the future, as is inherently necessary for spiritual evolution. We will likely inhabit all sorts of human forms, of different ethnicities, genders, and various physical characteristics. We will be born into different societies and experience a myriad of circumstances. Therefore, any notion of being “superior” or “privileged” is quickly erased. Through each lifetime, we learn, wittingly or unwittingly, how to live a noble and righteous life. We all will make many errors but over time learn from our mistakes, sometimes slowly.

This is where karma has a great influence. The Sanskrit word karma means action or deed. It is sometimes translated as the law of retribution and refers to the law of cause and effect. Even so, it is not punitive and does not give rewards in the sense of “bad” karma and “good” karma; rather, it is always a consequence of thought and behavior in order that we may open our eyes.

Annie Besant writes the following in her book Esoteric Christianity:

As every object has two sides, one of which is behind, out of sight, when the other is in front, in sight, so every act has two sides, which cannot both be seen at once in the physical world. In other worlds, good and happiness, evil and sorrow, are seen as two sides of the same thing. This is what is called karma—a convenient and now widely used term, originally Sanskrit, expressing this connection or identity. (Besant, Esoteric Christianity, 165)

Our life circumstances are created from karmic consequences, individual and collective, to optimize our opportunities for development. We may wish to rise to prominence and positions of importance, but these will not necessarily fulfill our duties, nurture our loved ones, advocate for social equity, or deepen our understanding of our larger world. Leonardo da Vinci is quoted as having said, “Wisdom is the daughter of experience,” and humorist Will Rogers once quipped, “Good judgment comes from experience, and a lot of that comes from bad judgment.” Others have expressed similar sentiments. This notion at its heart is very theosophical. We have an opportunity to learn from our mistakes. How quickly we assimilate these lessons is up to us.

When there is discussion of the planetary chains, rounds, and races in Theosophy, some eyes gloss over. This can be a challenging topic both because of its complexity and because of the vast sums of time involved. Just as a human physical life is only “one day” in our true existence, the history of our planet is also only one day in its existence. We are told that our present earth is one “globe” in a series of seven incarnations, descending from the spiritual planes into the physical and then back again to the spiritual. The middle globe of the sequence is our present earth. It is the most material, for it presides at the bottom of the loop schematically. Of course, these are not actually separate planets in separate places but merely the vibrational state and stage of development at a specific time. For each globe, seven “Root Races” occur. It must be clear that these are not races in the modern sense. Instead, they are epochal expressions of humanity. We are presently in our fifth Root Race on this planet, the full complement being seven. The descriptions of prior Root Races can be mystical; the previous one (the fourth) is said to be Atlantean. Each Root Race has subraces, again seven in number, and we are presently in the fifth, moving toward the sixth.

In addition, each cycle through seven globes constitutes one “round.” The life wave that moves through the globes descends into matter and ascends back into spirit, as previously noted. Seven of these rounds, also descending into matter and reascending into spirit, constitute a “chain.” Leadbeater writes:

Each chain consists of seven globes, and both globes and chains observe the rule of descending into matter and then rising out of it again. In order to make this comprehensible let us take as an example the chain to which our Earth belongs. At the present time it is in its fourth or most material incarnation, and therefore three of its globes belong to the physical world, two to the astral world, and two to the lower part of the mental world. The wave of divine Life passes in succession from globe to globe of this chain, beginning with one of the highest, descending gradually to the lowest and then climbing again to the same level as that at which it began. (Leadbeater, 121–22)

Humanity is presently also at the fourth round of this chain. Therefore, when looking at the entire planetary scheme, we are just slightly past the midpoint, still nearly in the most material (and least spiritual) form. Our globe forms the nadir of the cycles, and our Root Race, being the fifth of seven, is just slightly past it. The aforementioned Atlantean civilization would be the direct midpoint.

Leadbeater goes on to say, “There are ten schemes of evolution at present existing in our solar system, but only seven of them are at the stage where they have planets in the physical world” (Leadbeater, 124). This means that the other planets in our solar system are not inert pieces of rock and ice. Rather, they are the lowest physical manifestation of a complex series of globes that support the evolution of life of a description that is difficult to fathom. And our solar system is only one of an infinite number in the universe, where similar schemes of evolution may be taking place.

Each night passes into day, winter is followed by summer, birth is followed by death. We see cycles and periodicity everywhere. Our planet, solar system, and universe are no different. Each phase of manifestation is cyclical, having an outbreathing and an inbreathing. In Theosophical terms, the period of manifestation is known as a manvantara, and the period of nonmanifestation (or rest) is known as pralaya. Mme. Blavatsky, in The Secret Doctrine under a section known as the Three Fundamental Propositions, writes, “The Eternity of the Universe in toto as a boundless plane; periodically ‘the playground of numberless Universes incessantly manifesting and disappearing,’ called ‘the manifesting stars,’ and the ‘sparks of Eternity.’ . . . ‘The appearance and disappearance of Worlds is like a regular tidal ebb, flux and reflux’” (Blavatsky, Secret Doctrine, 1:16–17).

The expanse of time and space can be mind-boggling. The time for a major cycle of manifestation (maha-manvantara) is said to be in the hundreds of trillions of years. Mme. Blavatsky has been criticized for offering a “system” that is too complex and abstract to be accepted by the general public. It is curious that the same concerns have not been applied to quantum physics and viral immunology.

No discussion of Theosophy can be complete without reference to the Masters of Wisdom. As evolution progresses and humanity unfolds, some people reach the pinnacle of existence and become “perfected beings.” Of these, some, through their own choice, remain to assist and elevate humanity. These beings are known as the “Masters of Wisdom,” the “Adepts,” the “Arhats,” or the “Mahatmas” (Sanskrit for great souls). In her book on the Masters, Annie Besant writes, “The great religions bestow on this Perfect Man different names, but, whatever the name, the same idea is beneath it; He is Mithra, Osiris, Krishna, Buddha, Christ—but he ever symbolizes the Man made perfect. He does not belong to a single religion, a single nation, a single human family” (Besant, Masters, 1). HPB writes that “a Mahatma is a personage who, by special training and education, has evolved those higher faculties and has attained that spiritual knowledge, which ordinary humanity will acquire after passing through numberless series of reincarnations during the process of cosmic evolution, provided, of course, that they do not go, in the meanwhile, against the purposes of Nature” (Blavatsky, Collected Writings, 6:239).

The Adepts who retain an interest in our fledgling earthly existence have been described as the “Great White Brotherhood.” The phrase is not meant to have any implication regarding race or gender (white refers to light, brotherhood to all humanity), as the Masters are free of these attributes, except when they occasionally take physical bodies as vehicles.

The Masters attempt to guide the evolution of our species, and two in particular have been responsible for the development of the Theosophical Society as well as other religious initiatives in our history. Those two are known as Master Koot Hoomi and Master Morya (often known by their initials: K.H. and M.). Mme. Blavatsky said that they live “beyond the Himalayas,” although they do travel astrally and occasionally in physical form. Blavatsky was a disciple of the Master Morya and met him on several occasions.

In the early days of the Society, A.P. Sinnett, an Englishman living in India who was interested in Theosophical ideas, asked Blavatsky about initiating correspondence with the Masters. She encouraged him to try, and over several years there was an exchange of written communication. These letters have survived and are known as the Mahatma Letters. Initially a private exchange, decades later they were published, and the originals still exist at the British Library in London. The letters have been a rich resource of Theosophical theory and instruction and are revered by many students of Theosophy. N. Sri Ram, a late president of the Theosophical Society, notes that “all the Adepts of whom mention has been made have physical bodies, but many, we are told, do not have such bodies but remain in touch with the earth in their subtle bodies: they have not gone away from the world” (Ram, 5). The work of the Masters is thought to be behind some of the deepest religious and philosophical writings that have been provided through others over the centuries. K.H. writes, “This Theosophy is no new candidate for the world’s attention, but only the restatement of principles which have been recognized from the very infancy of mankind” (Beechey, 109–10).

What, then, is the purpose of life from a Theosophical perspective? This question has no single answer but varies by perspective and emphasis. We are beginning the return path to Divinity from our deepest excursion into materiality. This is a natural cycle of humankind and of consciousness. It is accomplished through character development, compassion, and service. Gaining knowledge through the doctrine of the eye and intuitional wisdom through the doctrine of the heart are both critical. By being aware of deeper states of existence through knowledge (study) and experience (meditation), we can develop spiritual wisdom. Annie Besant, writing about yoga (meaning deep, spiritual union, not simply postures or asanas) says that

Desire must cease; and the Self-determined will must take its place. The last object of desire in a person commencing the Path of Return is the desire to work with the Will of the Supreme; he harmonises his will with the Supreme Will, renounces all separate desires, and thus works to turn of the wheel of life as long as such turning is needed by the law of Life. Desire on the Path of Forthgoing becomes will on the Path of Return; the soul, in harmony with the Divine, works with the law. (Besant, Introduction to Yoga, 134)

Discussing the purpose of life, Leadbeater describes the downward arc into materiality and the upward arc into spirituality this way: “In this stage the spirit, having learnt perfectly how to receive impression through matter and how to express itself through it, and having awakened its dormant powers, learns to use these powers rightly in the service of the Deity” (Leadbeater, 108–09).

Socrates is famous for saying, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Perhaps this is a succinct way of noting that introspection, self-observation, self-understanding, and striving to ascertain life’s purpose are essential to the inner development of the soul during our terrestrial journey. Who we are and how we relate to ourselves, our fellow travelers, our environment, and our collective Divinity define our nature in the present. Our potential, however, goes much further. Legitimate spiritual teachers have attempted to point the way. We can take comfort in the fact that many, both ancient and modern, have traveled this path before us. However, none of them will carry us over the threshold. We must each take our own steps and find our own way. Each path will vary in its challenges and accomplishments.

To be an adherent of Theosophy requires no belief in doctrine, save the unity of all humanity. Each is free to explore avenues and corners to which he or she may be attracted. There is no need to recite or even believe in any particular teaching. We are constantly being told not to accept a specific concept because it was spoken by someone with recognition or written in an acclaimed book. We are counseled to explore for ourselves, to search where we may, and then to make up our own minds. We need not delve into the writings of the Masters, or even acknowledge their existence. If Mme. Blavatsky’s writings are too recondite, many other authors are available. If we find the talk of globes, rounds, and chains overwhelming, we need not dwell on them.

Theosophy, like all traditions, has a history variegated with personalities and opinions. But it is something much more. It has an aliveness and an immediacy. It begins to lift the veil of life’s secrets. It embraces the mystery of who we are and what we can accomplish. It vibrates deep inside us and emanates through our universe, seen and unseen. It is the love we share, the joy we touch, and the common link of all we experience. Each breath brings us closer to Divinity. Blavatsky told her students:

There is a road, steep and thorny, beset with perils of every kind, but yet a road, and it leads to the very heart of the Universe: I can tell you how to find those who will show you the secret gateway that opens inward only, and closes fast behind the neophyte for evermore. There is no danger that dauntless courage cannot conquer; there is no trial that spotless purity cannot pass through; there is no difficulty that strong intellect cannot surmount. For those who win onwards there is reward past all telling—the power to bless and save humanity; for those who fail, there are other lives in which success may come (Blavatsky, Collected Writings, 13:219).

Sources

Beechey, Katherine A., ed. Daily Meditations: Extracts from Letters of the Masters of Wisdom. 2d ed. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1984.

Besant, Annie. The Ancient Wisdom. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939.

———. Esoteric Christianity. 2d ed. Wheaton: Quest, 2006.

———. The Masters. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1918.

Blavatsky, H.P. The Key to Theosophy. London: Theosophical Publishing Company, 1889; Pasadena, Calif.: Theosophical Publishing Press, 1995. Citations refer to the 1995 edition.

———. Collected Writings. Edited by Boris de Zirkoff. Fifteen volumes. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1966‒91.

———. The Secret Doctrine. Edited by Boris de Zirkoff. Two volumes. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993 [1888].

Carlson, Reed. “Foreknowledge of the Wave/Particle Duality of Light.” Theosophy World Resource Centre website, Dec. 1, 1997: https://www.theosophy.world/resource/foreknowledge-waveparticle-duality-light.

Leadbeater, C.W. A Textbook of Theosophy. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1912.

Ram, N. Sri. Seeking Wisdom. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1969.

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

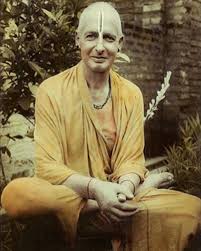

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy.

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy.