Love for the Living Earth: An Interview with Matthew Fox

Printed in the Fall 2022 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard, "Love for the Living Earth: An Interview with Matthew Fox" Quest 110:4, pg 14-19

By Richard Smoley

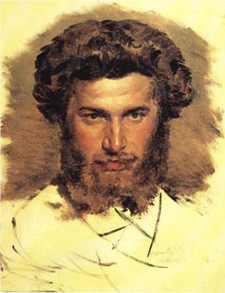

The maverick theologian Matthew Fox has been one of the most influential figures on the American religious scene for decades. Beginning as a Dominican monk, Fox was forced out of the order after clashes with Vatican authorities, notably Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI).

Fox is best known for his book Original Blessing, although he has written over three dozen others. He is also known for promoting his own theology of Creation Spirituality, which emphasizes the blessings of life as opposed to sin, guilt, and redemption.

His latest book, Essential Writings on Creation Spirituality, published in March 2022, contains excerpts from his writings, which address subjects ranging from creativity to dreams and visions, great mystics of the past, prophecy, activism, and the nature of the church.

This interview with Fox was conducted via Zoom in April 2022.

Richard Smoley: Your latest book is entitled Essential Writings on Creation Spirituality, so let’s begin by having you explain what Creation Spirituality is.

Matthew Fox: The word creation is really important. For too long, our thinking begins with humans. But the new science tells us a new creation story: the universe has been here for 13.8 billion years, and it is the height of arrogance, I think, to begin with humans. A lot of our ecological crisis derives from this anthropocentrism, from what Pope Francis, in his fine encyclical on the environment, calls the “narcissism of our species.”

Matthew Fox: The word creation is really important. For too long, our thinking begins with humans. But the new science tells us a new creation story: the universe has been here for 13.8 billion years, and it is the height of arrogance, I think, to begin with humans. A lot of our ecological crisis derives from this anthropocentrism, from what Pope Francis, in his fine encyclical on the environment, calls the “narcissism of our species.”

Even the Bible doesn’t begin with the human. The first chapter of Genesis has a cosmology that begins with light, and then proceeds to the moon, the earth, the animals, and the plants. Humans come at the very end. All of it is called “good” (which can also be translated as “beautiful”), and at the end it’s all called “very good.”

It is appalling: 95 percent of Christian preachers begin with chapters 2 and 3 of Genesis, which are about us and our failings. But that’s not the story; the story is that we’re part of a drama that culminates in our existence on this amazing earth, with amazing creatures—giraffes, whales, rain forests, and oceans—and it’s called very good and very beautiful.

Creation Spirituality thus begins with creation, not with the human. It’s also feminist, because the wisdom tradition in the Bible is about finding God in nature—Sophia. In fact, most people experience God in nature.

All this has tremendous implications for the earth crisis that we are undergoing today as we face extinction as a species. Creation Spirituality brings the sacred back to our worldview by acknowledging that the sacred begins with the universe itself. It’s bigger than ourselves, and we, like the other creatures, need to fit in.

This tradition is also prophetic in the tradition of Israel: wisdom is a friend of the prophets. The prophet in us is the person who says no to, who interferes with, injustice.

Many people ask, “Why haven’t I heard of this?” In part because Christianity has been carrying the legacy of the Roman Empire since the fourth century. At that time, Augustine was the primary theologian, and he came up with the idea of original sin, leading to a big detour by mainline Christianity. Original sin is not in the Bible: Jesus never heard of it, and no Jews had ever heard of it either.

Mainstream Christianity begins with the fall, not with creation. Empire prefers the notion of original sin, because it gets people doubting themselves; therefore they fall in line and join the army to conquer people in the name of Christ.

The Celtic tradition does not begin with the human; it begins with the cosmos. There have also been other great souls who begin with grace and spirituality and who inculcate the dimension of the divine feminine: Hildegard of Bingen, Meister Eckhart, Francis of Assisi, and many others. Thomas Aquinas saw the world in terms of Creation Spirituality, not in terms of fall and redemption religion. Julian of Norwich lived through the bubonic plague in the fourteenth century. Everyone at the time was going crazy, but she wasn’t. She was grounded in creation and said that God is the goodness in nature. She goes on about the nondualism of spirit and nature.

This is a very exciting and refreshing worldview. It has been sidelined by mainstream Christianity, but I think it’s coming into its own in our time. It’s exemplified in Pope Francis, not only by his choosing the name Francis, but in his fine encyclical on the environment, Laudato si. One scientist told me that Laudato si is the finest work on science and spirituality that the Vatican has ever produced.

There are real signs that we’re waking up. The question is, is this soon enough?

Smoley: How is Creation Spirituality coming into the social fabric? Is it happening within the churches, or outside the churches, in independent groups?

Fox: Both: both within churches and in spiritual movements, many of which are moving beyond organized religion. As you know, we’re hearing a lot of talk about the terms religion and spirituality. A very high percentage of people under thirty—I think the last figure I saw was 75 percent—don’t identify as religious, but they do identify as spiritual.

Religion moves very slowly: it’s a big ship that doesn’t have brakes, and it takes a long time to shift directions. Time is running out on Mother Earth. The latest scientific statement from the UN says we have at the most seven years left to change our ways if we’re going to prevent the worst effects of sea rising and climate change.

Young people don’t feel loyalty to an institution or a particular church. They’re trying to save the earth. And so they should: they have their future children and grandchildren in mind. Spirituality moves faster than religion.

That’s one reason I’m involved in a new order called the Order of the Sacred Earth. Unlike most other religious orders, it’s not beholden to any particular religion. This is a spiritual order. It’s about gathering people of all generations who have any spiritual tradition to bring to the table, whatever wisdom traditions have to teach us, that will contribute to compassion and to the saving of Mother Earth. But there are also some Creation Spirituality communities, which were founded by some students of mine, and they’re going very strong these days.

It’s not just a Christian thing. At our first ceremony for the Order of the Sacred Earth, there were Jews, Hindus, and Buddhists. It was actually held in a Buddhist temple. One twenty-six-year-old woman came up to me and said, “I’m an atheist, but I’m looking for a community that shares my values. My values are about the sacredness of the earth too, so I want to join.”

All orders have vows, of course, and the one vow we take is, “I promise to be the best lover of Mother Earth and the best defender of Mother Earth that I can be.” Of course, it’s very open-ended.

People from around the world have pods in different countries on different continents. We gather online once a month to share what our particular pods are doing. There are many ways of getting the word out, especially in this time of Zoom conferencing.

Smoley: You’ve outlined how Christianity was diverted off-course with Augustine’s doctrine of original sin. Where is Christianity as a whole right now—Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Protestantism?

Fox: The ecological crisis is deconstructing a lot of mindsets around organized religion, around Christianity. I think that is a litmus test. For example, fundamentalist Christians in this country are in denial about climate change. They have this weird idea that Christ is going to come on a cloud after a nuclear war, or after global warming drowns us all. That’s not Christianity. In many ways, it’s not religion, but politics. It’s an attitude of denial, because it’s easier than facing the facts.

Frankly, I don’t think we can look to the organized religions that much for leadership, but Pope Francis has done some very good things, such as Laudato si, as well as his criticism of extractive capitalism and the horrible, growing gulf between the superwealthy and everyone else. During the coronavirus, the billionaires have doubled their wealth, while all kinds of other people have fallen short.

I give Pope Francis credit for blowing the horn about some of these realities, but in fact the Orthodox church was ahead when it came to ecology, because the Orthodox church didn’t follow Augustine, who separated spirit from matter, saying, “Spirit is whatever is not matter.”

Aquinas in the thirteenth century turns his back on Augustine, saying that spirit is the vitality in everything: a blade of grass, a tree, a horse. There’s nondualism there. Today science says E = mc2—essentially, energy is spirit, so that’s very close to Aquinas’s view of the world. And the Orthodox tradition, refusing to follow Augustine’s doctrine of original sin, has put much more emphasis on the beauty and health of nature.

Right now, however, the Orthodox tradition is splitting over the invasion of Ukraine, so there’s a lot of internecine warfare going on there. The Russian Orthodox Patriarch of Moscow has been a buddy of Putin, whereas many Orthodox churches in different parts of the world—certainly in Ukraine—are breaking with him because he’s not stood up to Putin at all.

This is history, isn’t it? Yet poet Derek Walcott said, “The fate of poetry is to fall in love with the world in spite of history.” I think that’s a powerful statement, and it really applies to spirituality: we have to love this world, we have to love life, more than the disturbances and evil that are exposed in history. There’s something going on deeper than human history, and we want to fall in love with that and teach that. I think that’s the role of the artist, but it’s also the role of anyone who’s a spiritual person.

Smoley: You have criticized the notion of original sin, but even apart from that, there seems to be this very widespread sense, not just among Christians but among the human race, that there is something profoundly wrong with the world. There is the Buddhist concept of avidya: suffering and ignorance. Even primitive cultures often complain that the gods deserted humanity a long time ago. There seems to be a universal sense of something problematic, either in the world or in human nature. How does your theology work with that?

Fox: I wrote a whole book on evil, called Sins of the Spirit, Blessings of the Flesh: Transforming Evil in Soul and Society. If you look at apes, who are our nearest cousins in the animal world, they too have violence in them: they’re capable of wars and torture. It’s part of what we’ve inherited from our ancestors, so there are problems that we carry with us.

In my study on evil, I take the seven chakras of the East—the physiological, psychological, and spiritual centers of our bodies and psyches—and relate them to the seven capital sins of the West. When they’re healthy, each chakra is a point of love, of positive energy, but when they’re off-center—Aquinas says sin is misdirected love. That’s very Jewish: the Hebrew word for sin means missing the bull’s-eye. Hitting the bull’s-eye would be a healthy chakra, but missing it would be comparable to a capital sin.

Let me give an example. The seventh chakra is the culmination of the kundalini energy: the fire coming up our spine, working through all the other six chakras, and delivering light and good energy to other spirit beings, whether our ancestors, angels, or other humans who are trying to do good in the world. That’s building community when the seventh chakra is healthy. When it’s not healthy but off-center, it manifests as envy.

Envy recognizes the light in others, but instead of linking up with it to do good work, it wants to shoot down the other so that it’s the last one standing, if you will.

I think that the methodology of seven chakras and seven capital sins really works. We need a new language for evil today, because Western religion has so oversold sin that people don’t want to talk about it anymore. For forty-five years, I’ve talked to many Protestants and Catholics, and they tell me the same thing: by the age of fifteen, they’d already heard so much about sin.

We don’t have a working vocabulary for evil in our culture, because I think religion has failed us and has oversold the idea of sin. Because he was a Jew, Jesus never heard of original sin: no one had until the fourth century. As a theological category, it’s dangerous; it creates doubt about our beauty and our right to be here.

Yes, there is this quest to find out what’s missing in our species, but look at this: we now know of fourteen other hominid species who are our cousins, such as the Neanderthals and new ones discovered in Southeast Asia. All these are out of business; they’re extinct. That is a wake-up call: we humans are capable of extinction, and we’re really close to it right now. We have to clean up our violence—what I would call the reptilian brain unleashed.

Scripture says, “I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life” [Deuteronomy 30:19]. It’s a choice, a daily choice, not to choose those forces that are oriented to necrophilia instead of biophilia.

Smoley: This brings up the subject of pleasure, because the Christian demonization of sin is closely connected with the vilification of pleasure. What is a wholesome, balanced attitude toward pleasure?

Fox: The book of Wisdom says, “This is wisdom: to love life.” That’s what eros is, I think: a passionate love of life in all its expressions. Poet Audre Lorde says, “I’m erotic when I bake bread, when I make a table, when I write a poem.”

Eros is the wonderful gift of passion that we bring to everything we do. That includes sexuality, love of life, and many other expressions. I think that is to be honored and not held up for suspicion.

The Song of Songs in the Bible, sometimes called the Song of Solomon, is a celebration of lovemaking as an experience of the divine, as a mystical experience. In the Jewish tradition, you’re supposed to practice the Sabbath by reading the Song of Songs with your spouse and making love. Making love is not a sin; it is one of the profound ways in which we say thank you for existence.

Eros very much has its place. When Christ in John’s Gospel says, “I have come that you may have life and have it in abundance” [John 10:10], that’s eros; it’s a very erotic statement.

And of course Jesus himself was criticized for not fasting as heavily as his mentor, John the Baptist, did and for eating and drinking with the wrong people—partying. His meal experiences were important ways of bringing together the rich and the poor. He did it deliberately, so that all together in the same room, they would hear what he had to say and debate it.

The burden put on us by Christianity was derived, I think, more from Greek philosophy than from Judaism. It’s a burden that many are still carrying but can throw off. In undoing that burden, there’s a middle way that sees values as being true to your vows, such as not breaking your partner’s heart. Many young people today do not get married until their late twenties, so obviously there are going to be relationships and experimentation between adolescence and adulthood.

That’s another topic: rites of passage for young people. Christianity has confirmation, and Judaism has the bar mitzvah, but I question whether these are cutting the mustard at this time.

I draw a lot of energy, insight, and wisdom from indigenous people, who make a big thing of puberty rites of passage, especially for boys, because they feel that the girls have their own natural rite of passage with menstruation. The boys have to have a severe one; otherwise they grow up angry. I think that shows in our culture quite strongly: the lack of a real rite of passage for young people.

While we’re at it, we should also be looking at rites of passage for older people. The whole tradition of elders is very important. It’s not the role of the elder to play golf or play the stock market for the rest of their life. There’s something more serious going on. The elders should be relating to the youngest generation: grandparents and grandchildren. I think it would be appropriate to have rites of passage for elders which are designed with young people in mind and are attended by young people, so they get a fuller view of what life is about. This leadership is a real thing; it’s not just about tapping the heads of grandparents at Christmastime. It’s something important and necessary that goes on between the oldest and the youngest. The middle-aged, the parents, are too busy running the culture to really pay attention to that. I think we need a healthy eldership.

An anthropologist recently gathered a team to answer one question: why did the Neanderthals disappear while Homo sapiens is still going strong?

The previous theory was that we killed them all, but we now know that many of us have Neanderthal DNA in our genes, so we weren’t just killing them; we were making love with them.

This anthropologist found that Neanderthals tended to die around the age of forty or forty-two, meaning there were no grandparents, whereas we Homo sapiens live longer, so there were three generations: two of them raising the kids, not just one. I think that is important information, because it shows that the role of the elder is not about being put in a corner; they play a necessary role. I think this is in the memory of indigenous tribes, who honor the elders. They remember that they made it, not just because of their parents, but because of their grandparents.

Smoley: A great deal of your work has to do with refashioning the God concept. It seems that for many people, the traditional Christian image of God is outdated and no longer plausible; a new one somehow needs to be fashioned. How do you see this happening, and where do you think it should go?

Fox: First of all, I agree with you: it is happening. My favorite mystic, Meister Eckhart, says, “I pray God to rid me of God.” It’s pretty radical statement, but I think a lot of people are saying that prayer consciously or unconsciously today, because we’ve done an awful lot of horrible things in the name of God over the centuries, including killing indigenous religion, cultures, and tribes, slavery, and so much else. And of course God in America has become an overused term; we stamp it on our dollar bills and coins: “In God we trust,” which has led to an irreverence toward the transcendence of divinity.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a book called Naming the Unnamable: Eighty-Nine Useful and Wonderful Names for God. I got the idea for that book, again, from Thomas Aquinas. In his commentary on Pseudo-Dennis, the sixth-century Syrian monk, Aquinas says that every being is a name for God. The Vedas say God has a million names and a million faces, which is cool, but Aquinas is saying God is trillions upon trillions of beings. Every being is a name. I shared that with a friend of mine, who is a cosmologist, and he said it took the top of his head off just to hear that one sentence: every being is a name for God.

That’s what I do in my book with the eighty-nine names. I go to science for some of them, for example, “God is energy.” In his important book The Self-Organizing Universe, Erich Jantsch says, “God is the mind of the universe.” Then he says, “Previously mystics said this, but because I’m saying it as a scientist, a lot more people are going to hear.” That’s true: people listen more to scientists than to mystics, but then again plenty of scientists are mystics today.

Another scientist, whom I met at one of my book signings, says God is the mind of the earth, the earth mind, the earth intelligence. He talks about how there’s not enough time for the eye to have been invented by trial and error, certainly not by chance; it’s far too complex. He says there must have been an intelligence in that.

There was a fellow named Alfred Russel Wallace, who with Darwin birthed the evolution theory. Although he’s not nearly as well-known, he and Darwin worked together, and when they presented the first paper on evolution to the London science society, they did a back-to-back. Together they birthed the concept of evolution, but after many years of working together, Darwin and Wallace split over angels. Darwin said that this all happened by chance, but Wallace said that’s impossible: There’s been too much success in evolution for it just to be happenstance. There must be guiding intellects that assist in the process of evolution, and the word he used for them was angels.

Now I offer many other names for God, such as love, joy, justice, compassion, and beauty and, of course, the divine feminine, Kwan Yin. In the fourteenth century, Julian of Norwich, the first woman to write a book in English, spoke of God as mother and of Christ as mother and of the Holy Spirit as feminine. The point is that we have all these names for divinity. Your question is, which ones will come forward at this time, when we need them? There is, of course, the whole idea of Gaia, Mother Earth as a feminine deity, the feminine side of creation, and that’s found even within Christianity.

I think this is a wonderful time to be living: the lid is off, and we can move away from these images that have been dwelling in our psyches for a long time, like Michelangelo’s painting of God at the top of the Sistine Chapel, which shows an old man with a long, white beard, creating Adam—God as exclusively male.

Eckhart has some marvelous images; for example, he says God is the newest thing in the universe. God is not this old, tired, bearded guy, but the newest being in the universe—young, playful, fresh, invigorated, and excited about creation. One proposal in my book is that God is joy. Aquinas said that the universe was created partly because God wanted to have more company to share the joy of being with.

I think any name we give God opens up all kinds of avenues. We need to get the artists, the poets, the musicians, and the filmmakers on board to carry these new images.

Part of the new science is the idea that that the universe is unfolding and has been unfolding; it is growing and enlarging itself on a regular basis, and all this has to do, I think, with the built-in power of creativity. One of my books is called Creativity: Where the Divine and the Human Meet. I think the powers of creativity and cocreation are integral to whatever name we want to give divinity; divinity is very fertile.

Now we can say the universe is 2 trillion galaxies big, each with hundreds of billions of stars. It certainly stretches the imagination. The Webb telescope is going up in a few months, and it will be sending back, we hope, pictures of the original light of the universe. That’s stunning, because so many traditions around the world use light as the most common synonym for divinity.

When we think of light, we think of ordinary sunlight, but no, this is 13 billion years before the sun. That’s pretty amazing, and it could bring the human race together to wake us up so we cease making war against each other and against Mother Earth and preserve this amazing planet.

It’s time that we get smart and start acting grown-up. The human species has been at an adolescent stage for long enough, and we’ve got to grow up fast.

Smoley: As you said, Darwin had a brilliant idea, which is evolution by natural selection, but unlike Wallace, he made it into the single explanation for everything: all evolution was due solely to natural selection, as the neo-Darwinists still insist. Similarly, Marx saw that history is shaped by class struggle, so everything has to be explained by class struggle. Freud had the sex theory, so everything had to be explained by that. These geniuses seem to have been possessed by their own brilliant ideas. In a practical sense, how do you keep some sense of balance in your own thinking so that your ideas don’t become demons that obsess you?

Fox: I think narcissism comes in here: our ideas become our gods and goddesses, our idols. I think we need an appreciation of a bigger intelligence, wisdom, and love in the world to put our own efforts into perspective. I always say that we have a belly button to remind us that we didn’t make ourselves.

On the other hand, we don’t want to underestimate the good things we can do. Eckhart says that we’re always giving birth to the Christ; the Christ is always needing to be born. The Buddhists can say we give birth to the Buddha and to the Buddha nature, and the Jews say we give birth to the image of God. All that should be celebrated and honored, but that doesn’t mean that we displace the great Christ of the cosmos, which we are serving and we’re here to serve.

Then of course, we need to listen to one another and take criticism. It helps when you live in community: you keep each other within certain boundaries. I think your sense of humor is part of it too—the big laugh at ourselves and our theories.

People can get on their high horse and think that they’re more important than they are. We are all part of the lineage, and intellectually we do stand on one another’s shoulders. For a human, learning is a community effort.

No one is God, but we are all rays of God. The rays of the sun don’t displace the sun. We don’t displace God by whatever name or explanation we use.

Smoley: We hear a great deal about what’s going on in this country today, and this inevitably brings up negatives—gun violence, racial discrimination, environmental desecration—but that’s clearly not the whole picture. Even though those evils are there, there’s a lot of good counterbalancing them. I wonder if you could give us a panoramic view of what you see happening in the United States, neither omitting nor overemphasizing the good or the bad.

Fox: As I’ve said, necrophilia grows when biophilia is stunted. That’s a very profound statement on evil, and it shows us a way out of necrophilia. Life is really about biophilia; we have to fall in love with life on a regular basis.

I say we should fall in love three times a day. I don’t say that to threaten anyone’s marriage or relationship, but to get us out of our anthropocentric mindset. You can fall in love with the wildflowers, with trees, with stones, with animals, with planets, with galaxies, with music, with poetry. There is so much to fall in love with. I think when there’s enough falling in love going around, we will choose biophilia, the love of life, over necrophilia.

I do think there’s a lot of necrophilia happening as well; a lot of it is due to human inventions. We humans invent things, because we are so creative. The modern worldview accomplished a lot: for example, we got to the moon and back on Newtonian science. Electricity and similar developments made our lives better, but we didn’t calculate everything into it—what we were doing to Mother Earth, extracting her elements from the earth and of course killing indigenous cultures to get to these riches.

I think that we’re quite short-sighted about looking at consequences before they overwhelm us, so this generation is paying the bill for 500 years of profound neglect of Mother Earth.

Then we have hate radio, hate TV, and hate politics. It’s not just in someone else; it’s in all of us; we’re all capable of hate. But I don’t think it’s that esoteric to propose that, if you can’t in some way regulate our darkest passions, you can’t have a community that survives.

I do think that democracy is up for grabs in America today, as it is in many places around the world. A lot of it is not intentional, because we’ve got these modes of communication whereby you can pour your hate out, which then links to someone else’s hate. We’re all interconnected, not only about good things, but about bad things too.

We often underestimate the powers of our inventions. Do we have time to catch up before the dark side, the shadow side, overwhelms us? It is a time for being very alert and critical—not just of the other, but of self, of the role that we play in destroying the earth or democracy. How can we contribute together to save both?

We are living in notable times. We’re at a crossroad as a species, as is clearly the case with climate change. We all have to ground ourselves in the things you and I have been talking about: the goodness of creation, the presence of the divine and of love and justice. We have to fill ourselves with those things without being in denial about the suffering.

The present evil is a very powerful force; it’s smart; it doesn’t walk around with a sign on its back saying, “I’m evil; kick me.” It has lots of money in its pocket, and it goes where there’s power, whether it’s religion or government or the military. We can’t be naive about our capacity for evil or our capacity for extinction.

We have to move to the new level of humanity that all the great spiritual teachers, from the Dalai Lama to the Buddha to Muhammad to Jesus to Isaiah, are talking about. We’re capable of compassion, but it’s a bit of work to get there. We can’t be lazy, and we can’t just absorb the values of a materialistic culture. We have to offer something bigger, and that’s part of biophilia.

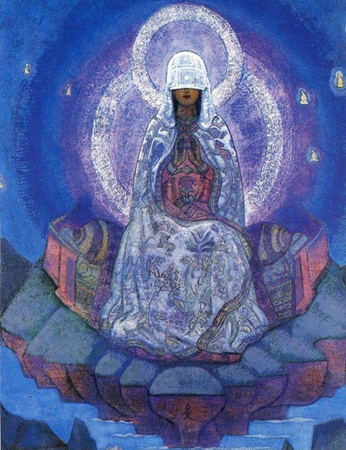

Nicholas Roerich (1874‒1947), artist, humanitarian, peacemaker, writer, educator, philosopher, explorer, and archaeologist, wrote, “In beauty we are united, through beauty we pray, with beauty we conquer.” He devoted his life to manifesting beauty in many fields of endeavor.

Nicholas Roerich (1874‒1947), artist, humanitarian, peacemaker, writer, educator, philosopher, explorer, and archaeologist, wrote, “In beauty we are united, through beauty we pray, with beauty we conquer.” He devoted his life to manifesting beauty in many fields of endeavor.

It is often said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. This statement suggests that beauty is subjective and that each of us has our own perspective of what is beautiful and what is not. Yet culture plays a tremendous role in our perceptions of beauty. This means that our perceptions of beauty are not our own; rather they are inculcated by the ideas of those around us. In other words, our perceptions of beauty are conditioned by both the world and the era in which we live.

It is often said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. This statement suggests that beauty is subjective and that each of us has our own perspective of what is beautiful and what is not. Yet culture plays a tremendous role in our perceptions of beauty. This means that our perceptions of beauty are not our own; rather they are inculcated by the ideas of those around us. In other words, our perceptions of beauty are conditioned by both the world and the era in which we live. t is easier to praise beauty than to understand it. Much of the writing on aesthetics attempts to limn the elegance of a given object without really telling us why we find it so.

t is easier to praise beauty than to understand it. Much of the writing on aesthetics attempts to limn the elegance of a given object without really telling us why we find it so.