Printed in the Winter 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Keene, Douglas, "Viewpoint: In Pursuit of the Golden Fleece" Quest 113:1, pg 10-11

By Douglas Keene

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

The ram rescued Phrixus, a youth who was about to be sacrificed by his father, the king of Iolkos (a city on the Aegean coast of Greece, which survives today as a village), and took him to Colchis, a region on the eastern coast of the Black Sea. Here Phrixus took refuge with the king, Aeëtes, and sacrificed the ram to Zeus. The ram was transformed into the constellation Aries.

Chrysomallos means gold wool, because the ram’s fleece was golden. Aeëtes hung it on an oak tree in a grove sacred to the Greek god of war, Ares. Here it was guarded by a large sleepless serpent, the Colchian Dragon. Jason, the mythological hero, embarked on a journey with the great hero Heracles and many warriors on a mighty ship, the Argo, to retrieve the fleece.

After a multitude of challenging adventures common among mythological figures (defined as heroes in these roles), and with the assistance of Aeëtes’ daughter, Medea, Jason succeeded in repelling all evil forces and obtained the object of his search.

On the way to fetch the fleece, Jason and his companions, the Argonauts, stopped in the land of the Doliones. Here they are confronted by Gegenees (whose name means aboriginals), hideous monsters with six arms. Led by Heracles, the Argonauts slaughtered the “stubborn, frenzied attackers” (as they are described in the famous epic poem the Argonautica).

In the legends of the Greeks and many other peoples, monsters, demons, devils, and serpents frequently appear as obstacles to attaining the target of pursuit. In terms of our own inner development, they are often metaphors for internal obstacles met when embarking on a spiritual journey, symbolizing the weaknesses and flaws that we must overcome to seek purification and redemption. They need to be “slain” in order for each of us to advance.

We usually find that the hero is assisted by an unlikely source, frequently with a divine connection, that serves as protector, guide and teacher. Each ordeal is calculated to strengthen the hero and deliver him or her through adversity in order to claim the prize. While many fail and fall, the hero will progress, even if it appears that all is lost at some point in the long and arduous journey.

There may be some fact behind this ancient myth. The Golden Fleece may sound entirely fantastic, but in certain regions of the Black Sea, the inhabitants used to put fleeces in rivers to trap flakes of gold. This may help explain this mystifying detail.

|

|

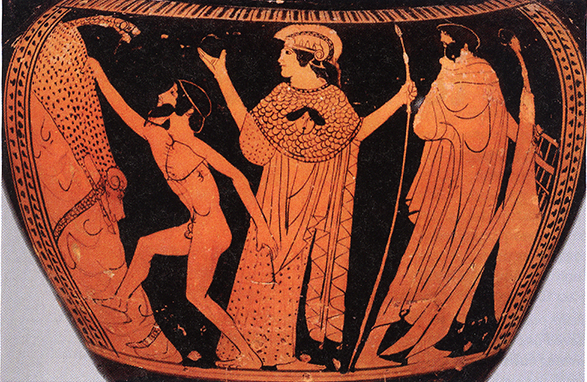

| Jason recovers the Golden Fleece from a sacred tree in the grove of Ares. The head of the fleece's guardian, Dragon-Serpent, darts towards the hero. The goddess Athena, wearing a helm and the aegis-cloak, oversees the endeavor. Behind her stands an Argonaut and the prow of the ship Argo. Attic red-figure vase, attributed to the Orchid Painter, c.470‒60 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

What is the message of this mythological journey? What does the Golden Fleece represent? One interpretation is that it symbolizes that which is nearly unattainable or cannot be easily possessed. Another is that the fleece is a symbol of refinement of sensitivity which elicits awakening and spiritual purity.

In any event, the hero’s journey is central to Greek mythology as well as to those of most cultures. It usually involves an arduous search for something elusive, something divine and powerful that is protected by obstacles of various kinds, fierce and mysterious, and often unknown.

The story of the Holy Grail in the Arthurian tales is another example. The earliest version of this legend (which has many variants) is found in the verse romance Perceval, written in the late twelfth century by the French poet Chrétien de Troyes. In it the youth Perceval (or Percival), seeking knighthood, sees the Grail in a mysterious procession in an enchanted castle. It is being carried by a young woman.

Perceval is curious about this strange procession but does not ask what it is about. Later he is told that this was a mistake, because if he had asked the “Grail question,” it would have removed a curse from the land. Perceval goes in search of the Grail, but in Chrétien’s unfinished poem never finds it. In another version, Arthur’s knight Sir Galahad, who is pure of heart, takes up this mission, and eventually has a vision of the Grail.

The Holy Grail has become synonymous with an object of great desire but is shrouded and sequestered, requiring great sacrifice to obtain. King Arthur realizes he is unable to find the Holy Grail, but perhaps his purified warrior can. These figures can be interpreted as aspects of ourselves.

As Joy Mills writes in Entering on the Sacred Way, “the hero of this legend is a guileless and innocent youth, a widow’s son, who is seeking a treasure hard to find . . . What is relevant to our present study is that in the Percival or Parzifal version of the legend we have a precise illustration of the requirements for discipleship, the essentials for the aspirant’s achievement of ‘kingship’ or ‘adeptship.’”

Here again we see the struggles of the protagonist searching with determination and sacrifice for the magical icon, willing to sacrifice all and abandon comfort, home, and community with the hope of reaching that sacred space. This resembles Gautama’s leaving the protection (or rather overprotection) of his family and high rank, to seek the world for purpose and truth. Eventually he attains enlightenment and becomes the Buddha.

Are these merely stories of people long ago and far away, or does its symbolism apply to our own lives? Is it relevant to our own challenges here and now?

H.P. Blavatsky wrote frequently about this quest for the nearly unattainable, and her book The Voice of the Silence is essentially a treatise on the spiritual path. In another important text, “There Is a Road,” she begins: “There is a road, steep and thorny, beset with perils of every kind, but yet a road, and it leads to the very heart of the Universe.”

“Perils of every kind” certainly can be intimidating. This is not a casual exercise, and these rewards do not come easily. The seeker must be willing to sacrifice all attachments in order to reach his or her goal. But as HPB tells us, for those who are committed to the journey—and ultimately to the “reward”—there is a path forward. If we are not ready, we will fail. But even in failure, lessons are learned. Failure is not permanent. Each adventure prepares us for the next.

Annie Besant, in her book The Outer Court, uses the metaphor of a temple with an outer court atop a mountain. She writes:

If we look more closely at the temple, if we try to see how that temple is built, we see in the midst of it a holy of holies, and round about the center are courts, four in number, ringing the holy of holies as concentric circles, in these are all within the temple . . . So all who would reach the center must pass through these four gateways, one by one. And outside the temple there is yet another enclosure—the Outer Court—and that court has in it many more persons than are seen within the temple. Looking at the temple and the courts and the mountain road that winds below, we see the picture of human evolution, and the track along which the race is treading, and the temple that is its goal.

This image metaphorically gives us the grand panorama to which most of us are blinded as, incarnated in a single lifetime, we struggle to find our own direction and goals. But by using the temple as a beacon, we can direct our progress by a much more focused and strenuous effort in finding our way up the mountainside. Even the interim goals may be largely unknown to us, but if we follow this guiding ideal, our travel will be rewarded.

Each of us may ask ourselves what we are committed to. What will be our Golden Fleece—that to which we are willing to sacrifice, to devote our efforts, our passion, and even our lives? Are we willing to plunge into the unknown and slay our demons and our impurities? It may seem to be a journey without end, and indeed may last many lifetimes. But we are not alone, and there is help for those who seek it. Are we ready?