Printed in the Winter 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Chapple, Jon, "Sri Krishna Prem: The Forgotten Theosophist" Quest 113:1, pg 31-34

By Jon Chapple

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy.

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy.

That Krishna Prem is not similarly remembered in Theosophical terms is largely due to his successful “adoption” by scholars of Vaishnavism, who have emphasized his public conversion to, and long-running association with, Vaishnavite Hinduism, as well as his hostility to institutionalized spirituality. (Vaishnavism is the form of Hinduism that worships the god Vishnu as well as his avatars, the best-known of which is Krishna.) Yet his books—all of which, to varying extents, are shaped by Theosophical thought—remain widely read among Theosophists, and the influence of Theosophy is felt even today at Uttar Brindaban (Mirtola), the Indian ashram he cofounded in 1930.

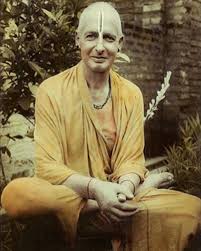

Born Ronald Henry Nixon in Cheltenham, England, on May 10, 1898, he moved to India in the aftermath of the First World War, in which his life, he believed, had been miraculously saved by a “power beyond our ken” while he was serving as a fighter pilot. In India, he cofounded a hilltop hermitage (Mirtola) dedicated to the Hindu god Krishna, for whose love (prem) he was named and to whom he remained singularly devoted for the rest of his life.

That is at least according to the popular version of the Sri Krishna Prem myth. In this telling, repeated in many biographical materials, Krishna Prem remained to his death a conventional Vaishnava in the Gaudiya (Bengali) tradition, serving Krishna in divine ecstasy to the exclusion of all other influences and teachers.

The true story—much like the man himself—is more complicated, charting a deeply personal spiritual odyssey that incorporated influences from Buddhism, Hindu Vedanta, classical yoga, analytical psychology, and the Western mystery tradition, alongside Krishna bhakti (devotion).

One legacy of Krishna Prem’s idiosyncratic and syncretistic approach to spirituality is that published accounts of his life—particularly by authors affiliated with a particular tradition or sect—tend to emphasize one aspect of his belief system at the expense of others. For Gaudiya Vaishnavas, Krishna Prem is notable as the first Western guru in their tradition. Steven Rosen, a disciple of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON, popularly known as the Hare Krishna movement), connects Krishna Prem’s final words with his guru’s journey to America, writing how “in November of 1965, on his deathbed, Śrī Krishna Prem had been documented as saying, ‘My ship is sailing.’ What he didn’t know, of course, was that the sublime ‘ship of Śrī Krishna Prem’ had, indeed, already set sail, just a few months earlier, headed for Western shores.” By contrast, psychologist Timothy Leary has written that his “interest in healing as well as enlightenment defines Sri Krishna Prem as a precursor of the humanist psychology movement that was to sweep America and Western Europe in the 1970s.”

The late Theosophist Seymour B. Ginsburg, a student of Krishna Prem’s disciple and successor Sri Madhava Ashish, has characterized Mirtola as a “Himalayan ashram with Theosophical rootsHimalayan ashram with Theosophical roots” (see his article in Quest, summer 2012, 98–105).

This article will focus on what Ginsburg calls the “deep Theosophical roots” underpinning Mirtola, as well as the influence of Theosophy on Krishna Prem’s spiritual journey, practice, and literary output.

Ronald Nixon is first documented as coming under the influence of Theosophical thought at Cambridge University, where he studied English and the “moral sciences” (philosophy), graduating in 1921. His Cambridge contemporary Christmas “Toby” Humphreys—who in 1924 would found the London Buddhist Lodge (later renamed the Buddhist Society) as an offshoot of a Theosophical lodge—described Nixon as a “silent, heavily built man, smoking his eternal meerschaum, and moving on the fringe of the Buddhist-Theosophical activities in which I was then involved.” According to Madhava Ashish, Nixon was given Buddhist diksha (initiation) by a senior member of the TS (possibly Harold Baillie-Weaver, then the general secretary of the Theosophical Society in England) around this time.

Hoping to better understand Buddhism and Hindu Vedanta in the land of their origin, as well as find an explanation for the psychic phenomena he is reported to have begun experiencing during his service with the Royal Air Force, Nixon wrote to the Theosophical Society at Adyar, hoping that his Cambridge degree and Theosophical connections might recommend him for a teaching post. His letter was forwarded to Gyanendra Nath Chakravarti (1863–1936), recently appointed the first vice chancellor of the new University of Lucknow. A meeting was arranged in London between Nixon and Bertram Keightley, Chakravarti’s disciple and a member of the university senate. The young graduate impressed his interviewers, and Keightley lent him money to get to Lucknow, then the capital of the United Provinces in northern India, to take up his new role as a reader (associate professor) in English at Canning College (incorporated into the University of Lucknow in 1922).

Nixon was already familiar with the most important Indian religious texts: his friend, the celebrated composer and yogi Dilip Kumar Roy, in his Yogi Sri Krishnaprem, wrote of listening with “rapt attention when he discussed the Vedas, the [Bhagavad] Gita, the Tantra, etc.” on one of his twice-yearly visits to Lucknow.

Nevertheless, it was in the person of Chakravarti’s wife, Monica, that Nixon found the living spiritual teacher for whom he’d been searching since Cambridge.

Monica (later known as Sri Yashoda Mai) was born in 1882 into a Theosophical family, one of three children, and the only daughter, of Rai Bahadur Gagan Chandra Roy (born 1848–49), a Bengali civil servant who was, among other postings, president of his local Theosophical Lodge (Ghazipore in the United Provinces, now Ghazipur in Uttar Pradesh). When she was twelve, Monica’s marriage was arranged to Chakravarti, a widower nineteen years her senior, then working as a lecturer in mathematics at Muir Central College in Allahabad. Though Chakravarti hesitated at first to remarry, having been left distraught following the death of his first wife, the match was a good one. Chakravarti shared many similarities with his new father-in-law: like Gagan Roy, he was a civil servant, Freemason, and committed Theosophist. As husband and wife, he and Monica were united both by their love for each other and by their dedication to matters of the spirit.

Chakravarti had joined the Theosophical Society in Cawnpore (modern Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh) in March 1883, and guests at the couple’s wedding in Ghazipore included prominent Indian Theosophists such as Tookaram Tatya, Aditya Ram Bhattacharya, and the future leader of the society, Chakravarti’s English-born disciple Annie Besant. Besant’s biographer, Geoffrey West, describes Chakravarti as a “mysterious Brahmin” who “for a number of years . . . hovers mysteriously in the background of Theosophical history.” Like Bertram Keightley, Chakravarti was an early student of HPB, and (along with Besant, Anagarika Dharmapala, and William Quan Judge) was a member of the Theosophical delegation to the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1893, representing the “orthodox Brahmanical Societies” of India.

Together, the newlyweds traveled widely on Theosophical business, including to Europe, where stories of Mrs. Chakravarti’s interactions with the locals in the company of Besant have passed into Mirtola lore. Simultaneously sought-after spiritual teachers and members of Lucknow high society, the Chakravartis are said to have lived something of a double life: outwardly a “resplendent ultramodern hostess,” Monica was, in the words of Dilip Kumar Roy, “the life and soul of every party she threw in her salon” at the vice chancellor’s mansion, while her husband was known as “an extremely hospitable man who kept an open table” for visiting Theosophists from England, among them Isabel Cooper-Oakley, the friend and disciple of Mme. Blavatsky, and Mary Tibbits (Mrs. Walter Tibbits), known for her The Voice of the Orient (1909).

Monica’s inclination towards Krishna bhakti is well known, and the story of her taking vows of renunciation, initiating Ronald (whom she called “Gopal”) into the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition, and founding the ashram at Mirtola has already been told elsewhere, and so is outside the scope of this article. What is less well known is the extent to which Theosophical ideas—particularly the belief in a brotherhood of liberated Masters guiding the spiritual development of humanity from afar— continued to hold sway over this supposedly orthodox Vaishnava ashram.

The Yoga of the Bhagavat Gita (1938), perhaps Krishna Prem’s most enduring literary work, has its roots in a series of articles originally published in the Theosophical journal The Aryan Path. Krishna Prem’s commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, as well as his view that it is fundamentally a “textbook of Yoga, a guide to the treading of the Path,” bears the influence of Annie Besant’s 1905 translation, which similarly focuses on the text’s symbolic significance while emphasizing the “oneness of the spiritual path, ‘though it has many names.’” (Compare this quote from Krishna Prem: “The Path is not the special property of Hinduism, nor indeed of any religion. It is something which is to be found, more or less deeply buried, in all religions.”) He also recommended Besant’s translation to his own disciples. In turn, Besant likely drew her inspiration from her one-time guru Chakravarti, who urged readers to “take Krishna as the symbol of the immanent God, the inner Godhead.”

Likewise, a contemporary reviewer for The Theosophical Movement argues that Krishna Prem’s next book, 1940’s Yoga of the Kaṭhopanishad, represents a Theosophical reading of that text, noting that Krishna Prem makes “copious and apt use” of Blavatsky’s Voice of the Silence and Mabel Collins’s Light on the Path “and more than once quotes the ‘Stanzas of Dzyan’ from The Secret Doctrine.” Krishna Prem, the reviewer writes, “has drunk deep at the fount of Theosophy and a comparative study of their interpretations of this great Upanishad proves most interesting. The present volume offers not only a more exhaustive interpretation but also carries marks of deep meditation on the esoteric teachings of the Upanishad.” The author also notes that Krishna Prem uses his part of his commentary on chapter one, verse nine, to defend Blavatsky—whose manifestations of letters from her Masters and other objects made her the target of criticism from skeptics—from charges of being a charlatan.

In the 1940s, with the encouragement of Keightley, Krishna Prem began his most overtly Theosophical work: a commentary on the Stanzas of Dzyan in Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine. As Gabriel Monod-Herzen, a friend of Dilip Kumar Roy’s and sometime visitor to Mirtola, noted in his review of the book, the project was something of a first: whereas texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and Brahma Sutras are the subjects of “innumerable commentaries,” to his knowledge “not a single Theosophist, Asian or European” had then written a commentary on the Stanzas of Dzyan. The resulting work, published posthumously as Man, the Measure of All Things in the Stanzas of Dzyan (1966) and Man, Son of Man (1970), was completed with the assistance of Madhava Ashish.

Krishna Prem’s enduring fascination with Theosophy, which rejects the concept of a personal creator (HPB once scoffed at what she called “the absurd idea of a personal God”), is incongruous in view of his initiation into a tradition which holds dear the concept of a supreme person. Regarding Man, the Measure of All Things, the scholar Andrew Rawlinson, in his Book of Enlightened Masters (1997), observes: “It is surely very odd that a committed Gaudiya Vaishnava should make use of such an unorthodox source” as The Secret Doctrine. The academic Catherine A. Robinson, in Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gītā and Images of the Hindu Tradition (2013), contrasts Krishna Prem with A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, noting that while the latter’s “association with this tradition [Gaudiya Vaishnavism] was generally orthodox, Krishna Prem’s was not.” (Swami was a fierce critic of those who denied or minimized God’s personhood and, in his essay “Theosophy Ends in Vaishnavism,” attacked the Theosophical view of “Sree Krishna [only] in His Impersonal Aspect Brahman” rather than as “the Personality of Godhead ‘Bhagwan.’”)

In 1951, following the death of Moti Rani, Yashoda Mai’s daughter (Yashoda Mai herself had died in 1944) and Krishna Prem’s disciple, Krishna Prem and his chosen successor, Madhava Ashish, began to further deemphasize Vaishnava ritual and theism in favour of a universalist, nonsectarian doctrine that Satish Datt Pandey (a disciple of Ashish) describes as a “secular and dynamic spirituality . . . that cannot be covered by any known cult label.” Both Moti Rani and her father, Chakravarti, were said to be in contact with the Masters, and ashramite Bill Aitken alludes to Krishna Prem also being in direct communion with these remote Mahatmas, writing that the “entire Mirtola makeover from orthodox to liberal I understood was at the promptings of the Theosophical Masters. The gurus saw themselves primarily as dedicated instruments of their Masters’ timeless spiritual sovereignty.”

By the early sixties, according to Aitken, “there was no Mirtola teaching as such,” with the two gurus, who referred to themselves as “pupil-teachers,” each pursuing their own philosophical interests—the former, Theosophy and the Sufi poems of Jalaladdin Rumi, and the latter, the Gurdjieff Work—and encouraging their students to do the same.

The teaching there “was adapted to [the] individual needs” of the practitioners, though it consistently drew on concepts introduced to the West by Blavatsky and her chelas. “The Theosophical understanding of the compassionate Bodhisattva concept was the backbone of their belief and teachings while I was there,” Aitken, who lived at the ashram from 1965 to 1972, tells me. Pervin Mahoney, another former resident of Mirtola, confirms: “This is an essential aspect of the mature final guide he [Krishna Prem] evolved into: that the man of attainment ‘remains available’ to help others.”

Krishna Prem also came to view a person’s spiritual progress in terms of their psychological “wholeness,” emphasizing the transformative power of love, meditation, courage, and hard work in order to rid oneself of unwanted habits and hang-ups. As Madhava Ashish explains:

[Krishna Prem] laid considerable stress on meditative practices, regarding them as the most essential part of the work, [but] he held that the work is not complete until the whole from which all things have come is reflected in the wholeness of the man. A man under the sway of inhibitions and compulsions he regarded as partial or incomplete. If through fear one attempted to avoid certain areas of worldly experience, then, when one turned to meditation, the inner or psychic causes of that fear would rise up and bar one’s progress. He therefore saw the work as a dialectical process: the facing of outer challenges opening the way to inner perception, and self-surrendering to the spirit in meditation giving rise to a trans-personal courage with which the challenges of life can be met. That self-surrender, he said, is the surrender of love, and the courage is the courage of love.

This idea has parallels in Theosophy: Light on the Path advises that the “whole nature of man must be used wisely by the one who desires to enter the way . . . Not till the whole personality of the man is dissolved and melted—not until it is held by the divine fragment which has created it, as a mere subject for grave experiment and experience—not until the whole nature has yielded and become subject unto its higher self . . . [can one gain access to] the Hall of Learning.”

Krishna Prem continued to work on the two Man books well into 1965, the year of his death: such is the importance he placed on The Secret Doctrine. “Extraordinarily,” he and Madhava Ashish “turned to this abstruse text with relish at bedtime after a hard day’s work on the temple and farm that began at 5 a.m.,” recalls Aitken, visiting in April of that year. “Pumping up a Petromax lamp to give brilliant light to replace the flickering flame of the kerosene lantern they sent away visitors at 10 p.m. and got down (on the floor) to some seriously introspective writing . . . The source of their enthusiasm was both mystifying and electrifying.”

Yet if The Secret Doctrine, like others, can serve as a useful reminder of the reality of the “path laid down by those who have gone before . . . and reached the goal,” the real truth, Krishna Prem taught consistently, is within, beyond teachers and ancient scriptures, and accessible to all. Like HPB, who urged us to “listen to the word of truth which speaks within you, and to the voice of silence, which can only be heard when the storm of passions has calmed down,” Krishna Prem wrote of “a Light within us which knows the Truth, a Voice which commands the right with absolute certainty” to which we need only listen. As he and Madhava Ashish remind us in Man, the Measure of All Things:

We have got so used to accepting it on external “authority” of some sort, that it is not easy for us to adjust ourselves to the idea that no authority whatever, whether of sacred scripture or whether of men, can guarantee truth, but that it reveals itself in all its infallibility within the pure consciousness. Hence, if we would learn wisdom, we must seek it not primarily in books or teachers but in our hearts.

Jon Chapple is a writer, historian, communications professional, and award-winning journalist based just outside of London. A spiritual seeker, he is also an amateur scholar of Vaishnavism and the bhakti yoga tradition. His debut book, the first full-length biography of Sri Krishna Prem, will be published by Blazing Sapphire Press in 2024. He can be contacted at jonchapple@gmail.com.