Printed in the Spring 2015 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Chambers, John."Riding the Waves of Karma: Memories of Muktananda's Ashram" Quest 103.2 (Spring 2015): pg. 61-65.

By John Chambers

The heart is the hub of all sacred places. Go there and roam.

-Sri Bhagawan Nityananda

It was like living in a cross between Dante's Purgatory and a Walt Disney animated feature film. A thousand faces filled the semidarkness. The air resounded with titters, groans, and guffaws. People rocked back and forth, assumed strange postures, thrust their arms up in the air. A steady buzzing like a swarm of bees came from the back of the auditorium. Over to one side a high-pitched cackle broke out. It was followed by a loud gurgling noise, and then the words, "Yum! Yum!"

It was like living in a cross between Dante's Purgatory and a Walt Disney animated feature film. A thousand faces filled the semidarkness. The air resounded with titters, groans, and guffaws. People rocked back and forth, assumed strange postures, thrust their arms up in the air. A steady buzzing like a swarm of bees came from the back of the auditorium. Over to one side a high-pitched cackle broke out. It was followed by a loud gurgling noise, and then the words, "Yum! Yum!"

A sock with a foot inside it brushed against my ear. The young man beside me was coming out of his headstand.

A small, dusky-colored man, about seventy years of age, wearing an orange ski cap, dark glasses, and a saffron robe, was advancing calmly through the cacophony. He moved quickly from person to person, stopping briefly to bop each one with a peacock-feather wand. Sometimes he lingered for a moment to pat someone's head as if he were testing the strength of the skull. Then he went on.

This man's name was Paramahansa Muktananda. Everybody called him Baba. He was one of the bestknown of the numerous spiritual teachers who spent time in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. This was the summer of 1979. I was in the meditation hall in Muktananda's ashram in South Fallsburg, high up in the Catskills sixty miles north of New York City. This big, sprawling collection of buildings, limned with fresh gardens and honeycombed with rooms large and small, was the headquarters of Muktananda's Siddha Yoga Dham (or "Home of Siddha Yoga") of America Foundation (SYDA).

I wasn't there for the sake of my soul. I'd come as a journalist covering New Age events. I also hoped to get rid of my smoking habit. I'd been told that if you chanted and meditated in the Siddha Yoga fashion, and especially if you spent time in Baba's ashram, you could expect to burn away bad attitudes and bad habits and make it as if they'd never existed.

This was my first weekend at the ashram. I would be staying for a month. Now I was huddled together with a thousand other attendees in a weekend-long intensive. The auditorium hadn't ceased to reverberate with bizarre and disconcerting sounds. Somebody screamed. Wild laughter broke out everywhere, cascading in merry waves across the hall. There was a sound like a steam whistle going off. Then there was a high-pitched wail. Abruptly the room was plunged in silence.

I fixed my gaze on Muktananda, who was advancing down the row where I was sitting. He was unperturbed as he made his way through this agitated, noisy throng. His peacock-feather wand flicked regularly up and down, while with one hand he reached out regularly to pat somebody's forehead. He strode forward with an oddly loose-jointed gait, shoulders thrust back, belly forward, as if he were a pregnant woman. But it was he who was doing the impregnating. I'd been told that the big circles, or "eyes," on a peacock feather were supposed to possess the power, not only to impregnate peahens from a distance, but also to seed the souls of men and women.

And that was what Baba was doing. He was sowing a seed in each of us. When he stopped and touched a head, it was to make sure the seed had fallen in the right place. In the language of Siddha Yoga, Baba was administering shaktipat; he was awakening the shakti, or "conscious energy," in each of us. That energy was coiled up snakelike at the base of the spine in a configuration called the kundalini. Baba's own kundalini had been brought to full maturity long ago, or so we had been told; by dint of years of meditation and chanting, it had mounted up through his spinal column until it reached his brain and then his soul. The shakti was alive in Baba from head to toe. He had become what is called in Siddha Yoga parlance â"firmly established in the Self"the greater, cosmic part of ourselves that the normal self, which has not known it since birth, seeks to reunite with. Muktananda was a fully realized human being, so brimming over with the bliss-bestowing conscious energy called shakti that he could awaken it in each one of us with a word, with a touch, with a look even with a thought! The peacock-feather fan was a conduit that the fire of Babaâ's shakti flowed through to reignite the guttering lamps of soul within us all.

It was the awakening of the kundalini that was causing all the commotion in the room. When the kundalini woke up, it found itself hemmed in by a mass of psychic debris. The way up the spinal column was only three feet long, but it was lined with psychic scar tissue samskaras, or "impressions" from your previous lifetimes. The kundalini had to fight its way through these samskaras through your bad karma, so to speak and they resisted powerfully and noisily; they liked it where they were, and were loath to cease to exist.

In that first intensive in the meditation hall, we all let off a tremendous amount of psychic steam. The awakening shakti assaulted, broke up, and forced out the hard, resistant, blackened accretions of many a badly lived lifetime. That was the reason for all the giggles, screams, guffaws, all the bizarre and unclassifiable sounds that erupted in the auditorium: people were disgorging "negativities"; they were letting go of bad karma; in the parlance of Siddha Yoga, they were "having kriyas."

I looked up. Baba was standing in front of me. I felt the light tap of his peacock feather. Then he was gone. Fifteen minutes later, Baba ended his rounds and strode resolutely toward the front of the auditorium. He bounded up the steps that led to the stage and strode across to his young, black-haired, undeniably beautiful Hindu translator Malti (who, a few years later, as Gurumayi Chidvilasanda, would become Baba's successor as SYDA's leader). Uttering a few words which his excited audience couldn't hear because it was sending up a tumultuous roar, Baba raised his arms high like a prizefighter who's just won a fight, and then strode, purposeful as always, off the stage and away.

Muktananda Paramahansa was born to wealthy parents in south India in 1908. His father was a rich landowner. His mother was a cultured woman and a devotee of the god Shiva. He broke her heart (as he tells us sadly in his autobiography Play of Consciousness) when he left home at age fifteen in search of nothing less than total Self-realization. She knew he would never return, and he never did, though she saw him again a few times.

Muktananda tells us that he sat at the feet of sixty gurus. Enlarged black-and-white photos of several of them hung on the auditorium walls. They were a vastly eccentric lot by Western standards. One, Zipruanna, spent his time sitting on piles of excrement, and yet exuded a fragrance so psychically exquisite that if you came close enough you found yourself taking a giant step forward on the path to Self-realization. Another, Harigiri Baba, loved to don the clothes of rich men and sometimes wore two hats and three coats, but he, too, gave off such an odor of sanctity that you could not pass near him without evolving significantly as a spiritual being.

Baba scarcely mentioned those gurus in the talks he gave every night. The only guru he liked to talk about was Sri Bhagawan Nityananda (1897—1961). Nityananda had the distinction, so the lore of the ashram went, of being a janma siddha, that is, of having been born fully realized. He was seven feet tall. He dressed sparingly, mostly in only a loincloth. He almost never spoke. Yet he must have been a natural leader of extraordinary power, because for many years multitudes of people flocked to his ashram in Ganeshpuri, India, from every part of the world. A myriad of seeming miracles occurred when he was around, and he put the considerable donations that came to the ashram back into the town of Ganeshpuri.

Nityananda was the leader of the Siddha Yoga movement when Paramahansa Muktananda came to him in 1947, at the age of thirty-nine. In 1956 Nityananda bestowed upon him the "grace-bestowing" power of administering shaktipat, which effectively made Baba the new leader of the movement.

Baba remained at Ganeshpuri for some time. Then he came to the United States and quickly became popular. He was open to all and freely granted interviews. The Siddha Yoga mantra was neither a secret nor was it different for everyone, as was the case with Transcendental Meditation at the time; it was om namah shivaya ("I bow to Shiva"'Shiva being one's own Self), and you were encouraged to chant it on every possible occasion. It was Baba Muktananda's gift to the world. For even while staying in the U.S., Baba traveled the whole world, and in 1974 he began to set up ashrams everywhere. The South Fallsburg center was one of the first and most important.

At the ashram that summer, every evening we were in the presence of Baba at darshan in the auditorium. The guru spoke for two hours, never using notes and never repeating himself. Afterwards we filed down one by one to a throne he sat in just below the stage, and he bopped us with the peacock-feather wand. This was a dramatic experience, somewhat different from that at the intensive: just two or three feet from Baba, most of us, myself included, felt a hot blast of energy strike us as the peacock feather descended. Perhaps this made up for the fact that we saw little of Baba during the day. But, as the reader will soon learn, much was always happening beneath the surface of the ashram day and night.

Along with darshan in the evening, many hours were taken up during the day with chanting and meditation, alone, and in groups, and with classes every morning and afternoon taught by the saffron-clad swamis who lived at the ashram (most of whom were American, and some of them ex—university professors). We also "did seva," which meant carrying out tasks for the ashram for three or four hours a day. These could be anything from planning programs to doing accounts to washing dishes to weeding gardens.

I shared a room with three other ashramites. Talking to them taught me more about Siddha Yoga and the extraordinary culture of the ashram than anything else. But doing seva was almost as instructive as kibitzing, because you were participating in the everyday life of the ashram.

Doing seva was no act of reverence toward Baba. He had made it clear at the intensive that we were not there to honor or worship him, but to honor or worship our Selves. There was a sense in which he, Baba, was not a real physical being, but rather a stand-in for our own Selves. Whenever we did seva' whenever we did any sort of service for the guru'we were actually doing service for our Self, since the guru was the Self. And that meant that every bit of seva we performed pushed us a little further along the path to self-enlightenment.

I did seva in the ashram kitchen, washing knives, forks, spoons, and pots for three hours every morning or evening. One evening I was bent over the sink when an angular, skeletally thin woman of perhaps eighteen entered the huge kitchen (this part of the ashram had been a hotel that could serve 500 people a day). Sadness was written all over her thin and bony face, and especially in her eyes. She made her way slowly across the kitchen floor and disappeared into a cubicle on the other side.

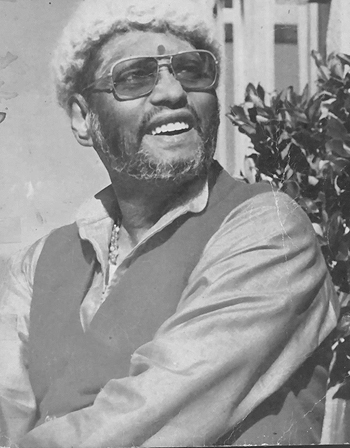

|

| Swami Muktananda |

My workmate Joey whispered in my ear, "See that girl? Her seva is cleaning one pot."

"One pot?" I exclaimed.

"I'll show you."

He led me across the floor to the cubicle door. We peered in. There rose before us a single, dented, silvery pot, monstrously large, four feet high and almost three feet across. The girl was on the other side, bent over so far into the pot that her head was almost lost from sight. She didn't notice us; she was scouring the insides slowly, firmly, evenly, with the utmost concentration.

She didn't notice us. We returned to our dish-laden sink. "She's been doing that for two hours every night for two weeks," Joey said to me. "Now that's seva!"

All of a sudden we heard gasps of surprise and joy just outside the door. We turned; the other ashramites in the kitchen were throwing themselves on the floor in various positions of prostration. And then Baba strode purposefully in, swift as a bullet, as smoothly as if he were rolling on castors. He crossed the floor to the cubicle door, looked in' and then, turning, strode back across the floor and was gone out the door just as suddenly as he had come in.

I hadn't had time to decide whether to prostrate myself or not. But Joey had thrown himself to the floor in a second, and now, scrambling back on his feet, he addressed me: "You see what I mean? That's seva that works!"

"He didn't even speak to her," I protested. "What was supposed to happen?"

"Wait and see," he said, in the tone of absolute certainty I often heard in the ashram.

I went about my business: classes, meditation, chanting, more meditation. It was very calming; but always, wherever you were, you regularly heard kriyas going off like rifle shots, sniffs, pants, shouts, and guffaws accompanying the sudden discharge of samskaras. I washed dishes every morning or evening. The girl scrubbed the pot every night; each time she left it looking as good as new.

On my last day at the ashram (many were leaving; a massive changeover of attendees was about to take place), I was sitting on a bench near the entrance when suddenly the usual signs'gasps of surprise, instant prostrations'signaled that Baba was just outside. There was the flash of an orange robe, a glint of sunglasses, a sudden rush of activity, aides scurrying forward'and then Baba strode swiftly, smoothly, and purposefully through the ashram entrance.

He stopped abruptly and turned in my direction. He strode rapidly towards me. And then I noticed (why hadn't I noticed before?) that my bench was occupied lifeby somebody else: the girl who scrubbed the huge pot every night.

Baba came up to her. He stood before her. She looked up in surprise. He reached down and took her hand. He swiftly removed his sunglasses and gazed down at her intently from eyes that seemed to me enormous.

She stared up timidly.

He held her hand. He spoke Hindi to her. Nobody moved; no translator came.

He gave off heat. Seated not three feet away, I could feel it, just as I could on the darshan line. It was if the door of an oven had been opened.

The girl softened in his gentle grasp. The corners of her mouth began to work. Joy swept across her face. Great round tears rolled down her cheeks, but all the time she was smiling happily.

Then he let go of her hand and was gone, as if his work was done'swiftly, into the depths of the ashram he had created.

Events like this took place at the ashram all the time. They were all we ever talked about. In our classes we learned about Kashmiri Shaivism, which was the philosophy behind Siddha Yoga. But outside class, all our talk was of karma, and especially of our personal karma. It was as if we were living a sort of karmic time in the ashram, not real time at all. Of course, bad karma could not be avoided, it had to be worked through; but we thought that if we truly became involved with Baba and all he stood for, if we meditated and chanted continuously in the ashram, Baba could take on our bad karma and burn it up in the fire of his own perfected being. What had to happen in your lifetime could happen in the ashram in a kind of compressed karmic time.

Or, at least, be launched. Your stay with Baba in the ashram was usually only the start. That period of "being with the guru" put mysterious karmic forces into play that, once you left the ashram, would make your life accelerate faster and faster, sometimes beautifully, often painfully, but in such a way that you would come out the other end a transformed, happier person.

One of my roommates, Ron, now a taxi driver, once a geologist, explained it all to me one night. Leaning back on the bed, scratching his lean, regular features and '50s crew cut, he told me that the year before he'd spent the summer at the ashram. And then:

"My life fell apart after I left the ashram. My wife left me in September. She was having an affair with my best friend. Then I couldn't find a publisher for my geology textbook. Then I lost my job."

"That must have been horrible," I muttered.

"It wasn't horrible at all. Just think what might have happened if I hadn't been at the ashram last summer."

"What might have happened?" I was genuinely puzzled.

He told me that it wasn't unusual for people's lives to fall apart after they'd spent time with Baba in the ashram; this was so their lives could fall back together again in the right way. It was truly amazing how fast everything happened once you got back to real life. "I was up to my ass in bad karma," Ron told me. "I was in a million situations I didn't like and that weren't good for me. If it hadn't been for Baba, my bad karma with my wife and my bad karma about being a scientist would have gone on forever."

Now he was driving a cab in the Bronx, living permanently in the Manhattan ashram, and seeing his eight-year-old son every weekend. "I listen to the Guru Gita," he said. "I drive my cab. I meditate. I get my soul in order."

I heard many stories like this at the ashram. I found them beguiling in their intimation of vaster dimensions in our lives which we can never really grasp but which play decisive roles. I heard stories of reincarnation and of how dipping into your past lives could give you strength in this one, or change it (or even change a past life!), and that being with Baba at the ashram was the catalyst that could make this happen.

A new friend of mine, Jim, a writer I talked to every day, told me that on the first day of class he'd noticed a woman whose luxuriant blond hair was utterly familiar to him. So were her shapely shoulders. So were her huge black eyes. He felt as if he'd known her all his life, though he'd never seen her before.

All this he observed from a distance. After class, he couldn't catch up with her. An hour later, while in a line waiting to get into the cafeteria for lunch, he looked down and there she was, standing beside him, head with its luxuriant growth of blond hair not quite coming up to his chin. She'd noticed him no more than he'd noticed her. Now she glanced up suddenly, stared at him, and said, "You remind me of the first boy I ever went out with."

They spent the afternoon walking and talking in the gardens. They were sure they'd been lovers in a previous lifetime. Nothing happened between them that afternoon, or in any of the days that followed, though both were unhappily married. They seemed to derive tremendous strength from this encounter, which really ended on that day. "It was like coming to an oasis in the desert," Jim told me. "It helped me a whole lot. And I know what to do about my marriage now."

Another of my roommates, Roger, told us one morning that he'd dreamt about us all that night. "We were soldiers in a kind of medieval German army," he said. "We had these strange, distinctive boots on. And we all hated each other. We were in the same army and we had a common enemy but we hated each other. We did awful things to each other."

That was all he could remember. He was sure the shakti had brought us together in this room this summer so we could move beyond that miserable, shared lifetime. And all of us had to admit that we'd felt strangely wary of each other when we'd arrived at the ashram, though now we were feeling much better.

It was these personal dramas'which seem to me to this day to have tapped into unique and unknown parts of the human soul'that gave us all the sense of a heightened life at the ashram. I recall that life more fondly today than I do the (nevertheless estimable) classes in spirituality and metaphysics I took there.

And I had my own personal drama. I'd hoped to leave my smoking habit behind at the ashram. Smoking was forbidden there, so I didn't smoke for four weeks. When I left, I not only no longer craved a smoke; I could hardly remember what a cigarette was. I can still hardly remember.

In early 1982, not long before Baba's death in November, scandal invaded the Siddha Yoga Foundation. Baba was accused of having sexual relations with young women. I didn't hear about this till November 1994, when I read about it in a story in The New Yorker.

At the time of the writing of the New Yorker story, twelve years later, it was still not clear what had really happened. Some argued that what Baba had engaged in wasn't really sex, but a sexualized form of spirituality. But there were those who left the Siddha Yoga Foundation on account of these rumors, and Baba's actions, whatever their true nature, cast doubt on his integrity and that of the movement as a whole, and were certainly counterproductive.

The scandals did not cease with that. The year before he died, Baba had designated, amidst some confusion, two cosuccessors to himself in SYDA: Malti, his interpreter and assistant for ten years, and Subhash, her younger brother, whom Baba renamed Nityananda. For three years, this sharing of the Siddha Yoga leadership seemed to work fairly well. Then, in 1985, Subhash/ Nityananda was cast out, and not without some violence. The New Yorker story provided many details; it seems as if for a while there were severe perturbations in the karmic space-time reality of the Siddha Yoga Dham. After that, Malti/Gurumayi Chitvilasanda assumed full leadership, and the Siddha Yoga Foundation quickly got back on an even keel. It is a great pity that, just before he died, Muktananda (out of generosity, and not a little indecisiveness) bestowed upon two people he loved, Malti and the younger Nityananda, immense power which, in the beginning, they not surprisingly had little idea how to handle properly.

In the summer of 2013, I paid a visit to the Siddha Yoga Center in San Diego, California. Services were conducted as they'd always been. The same portraits of Muktananda and Nityananda as had graced the walls of the auditorium at South Fallsburg in 1979 hung on these walls. A portrait of a strikingly attractive Gurumayi Chitvilasananda was the only addition.

The subject of the foundation's travails in the early 1980s did not come up. It was as if that drama had run its course and now could cease to exist.

For this writer, the moral of these stories of scandal is that gurus, like every other man or woman who attains to some degree of power, can, when they've gotten older, and especially when they're surrounded by adoring disciples, lose for a moment their grip on their better self and fall into the sin and folly and simple mistake-making that all human beings are always precariously near.

Before the scandals overwhelmed Paramahansa Muktananda, he had for many decades been providing essential help to thousands if not tens of thousands of suffering, yearning human beings. This writer is convinced that he was driven all his life by a profound and selfless desire to benefit humanity. In this, he succeeded to a degree matched only by a few, and to an extent that any indiscretions at the end of his life can surely be forgiven.

Beyond all colorful stories in The New Yorker, beyond all cynicism, beyond all irony, it was to mankind's suffering that Muktananda addressed his life. Often, leaving the auditorium stage after darshan in that summer of 1979 in South Fallsburg, he would raise his arms and ringingly repeat the mantric words sadgurunath maharaj kijay, which mean:

All hail the conquering guru.

This writer bows to that.

Sources

Harris, Lis. "O Guru, Guru, Guru." The New Yorker, 70:37 (Nov. 14, 1994), 92—109.

Muktananda, Swami. Play of Consciousness: A Spiritual Autobiography. South Fallsburg, N.Y.: SYDA Foundation, 1978.

John Chambers is the author of a number of books, including Conversations with Eternity: The Forgotten Masterpiece of Victor Hugo, which has been translated into seven languages; Victor Hugo's Conversations with the Spirit World: A Literary Genius's Hidden Life; and The Secret Life of Genius: How Twenty-Four Great Men and Women Were Touched by Spiritual Worlds. His latest book, Isaac Newton: Rescuing the Soul of Man, will be published in mid-2015. He lives in Redding, California.