Printed in the Winter 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Macrae, Janet, "On the Metaphysics of Aging" Quest 113:1, pg 35-39

By Janet Macrae

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

During the speaker’s explanation of the mental field, a woman raised her hand and asked an unexpected but significant question. “Is there any compensation for the memory loss that is frustrating for so many of us?”

After a few seconds of silence, a participant raised her hand and offered her personal experience of aging: “Although my memory is getting weaker—particularly my short-term memory—something inside me is getting stronger. I’m receiving more insights when I need to make decisions. Amazing coincidences are happening. And I feel I’m living more creatively now than when I was younger. This, to me, is compensation.”

The speaker responded to her statements by discussing the subtle field of buddhi, which exists beyond the mind as we familiarly know it. It is the source of intuitive insight, wisdom, creativity, and spiritual perception. Our appreciation of beauty comes from here, as well as our sense of meaning and purpose. It is a unitive level through which we see the underlying connections among objects and events rather than their separateness.

The speaker explained that we can cultivate the buddhic consciousness in many ways, for example by artistic activity, paying attention to dreams and synchronistic events, and regularly engaging in spiritual practices such as meditation and contemplative prayer. If we are open to new insights and are willing to change our behavior in accordance with them, the inner wisdom-intuition will guide, strengthen, and enrich our lives.

Unfortunately, only an hour had been allotted for this lecture, and it was soon over. I felt a wave of frustration as people were leaving because, with more time, the speaker could have responded to the woman’s question more fully. She could have discussed the cyclic journey of our consciousness and its significance for the aging process from the perspective of the Ancient Wisdom.

In the first phase of life, consciousness flows outward from its unitive source to gain experience in the material realm. In the later phase, consciousness begins its return: an inner reintegration process that continues in various stages after death.

The advantage for the aging population is that the tide of consciousness is now flowing in the direction of buddhi. From a metaphysical perspective, the aging phase is designed to bring us more in touch with the inner wisdom, peace, and creativity of a higher level of being. Although this dynamic design is working within us, its full actualization requires our conscious cooperation.

The Hindu concept of the four stages of life is based on the concept of the rhythmic pattern of consciousness. Huston Smith describes these stages in detail in his excellent chapter on Hinduism in The World’s Religions. In brief, the first stage is that of the student; the second, that of the householder; the third is that of retirement for study and meditation; and the final stage is that of the enlightened individual, whose outer personality is merged with the eternal, universal consciousness. The number of years in each stage is not specified, as perhaps it varies with the individual.

|

|

|

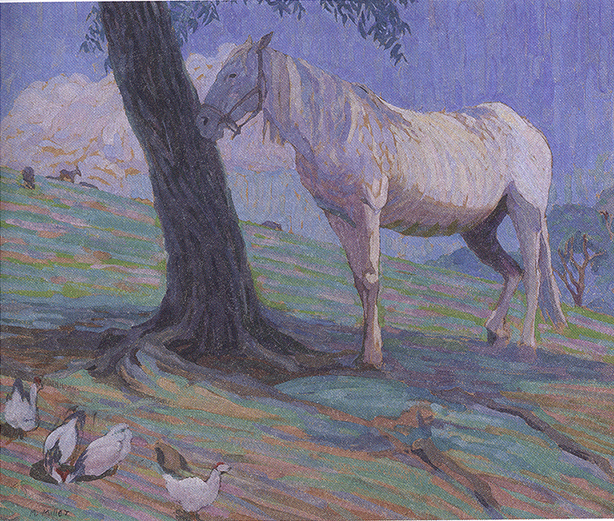

Untitled painting of an old white horse by Mildred Miller. About it she wrote: “Drawing an old white horse with a great lump on his side. “‘When that breaks he will die,’ said his owner. “The light was beautiful on the horse, and the color of the light on the grass, and the distance were too beautiful for words. There stood the old white horse waiting patiently for his initiation into the next stage. “Life—how I love it. And the horse perhaps has loved it too.”From Mildred Miller’s diary, probably from 1927, when she painted this image. In Mildred Miller Remembered by Virginia Brown. Photo by Christian Giannelli Photography. |

Smith concludes that our attitude is essential for the fulfillment of the promise of old age. If physical beauty and abilities or worldly accomplishments are valued most highly, the earlier stages of life will be the most interesting and satisfying. But if spiritual wisdom and self-knowledge are one’s greatest interest, the later stages can be the happiest and most fulfilling.

In the Western philosophical tradition, the best-known treatise on old age is De senectute by Marcus Tullius Cicero, written in 44 BC. The great Roman statesman wrote about an intrinsic natural rhythm and design to human life, in which aging has its appropriate place.

I follow nature as the best guide and obey her like a god. Since she carefully planned the other parts of the drama of life, it’s unlikely that she would be a bad playwright and neglect the final act . . .

Nature has but a single path and we travel it only once. Each stage of life has its own appropriate qualities—weakness in childhood, boldness in youth, seriousness in middle age, and maturity in old age. (Freeman, 13, 69)

As with a botanical harvest, the fruits of old age, according to Cicero, require active cultivation throughout all the seasons of one’s life. Nature’s play has been written, but the actors have to fulfill their roles.

We can become more aware of this intrinsic rhythm of consciousness by reading biographies, for often there is a noticeable shift in attitude, a reaching beyond one’s personal self, as an individual ages. This change can come through some great life challenge. It can also come, as the Catholic priest and mystic Richard Rohr has beautifully written, from an acceptance of the “necessary suffering” that comes from being human.

In Florence Nightingale’s long life (1820‒1910), this inner reorientation came through profound thought and an inner awakening. Well-known as the founder of modern nursing and a pioneer in statistical analysis, she worked tirelessly to help save lives by advocating for public health reform. Throughout her life, her work never changed. But in midlife, she experienced a major change in attitude. She began to integrate the ideal of karma yoga as described in Sir Edwin Arnold’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita: if work is done for the sake of itself, rather than for a specific result or reward, it can become a spiritual practice.

Nightingale’s early biographer Sir Edward Cook wrote that the ideal expressed in this text helped to “set the note” of the latter part of her life. “She strove to attain, and she taught others to ensue, passivity in action—to do the utmost in their power, but to leave the result to a Higher Power” (Cook, 2:241).

The renowned clairvoyant C.W. Leadbeater wrote that in the great cycle of incarnation, the midlife point is much more important than either physical birth or death, “for it marks the limit of the outgoing energy of the eg—the change, as it were, from his out-breathing to his inbreathing” (Leadbeater, 1:69). After midlife, therefore, one should follow the dynamic plan of nature and turn one’s thought to higher things. Leadbeater emphasized the importance of gradually resolving any interpersonal difficulties so that, looking back after death, one is not weighed down by regrets. Discussing the four stages of life in the Eastern tradition, he lamented the fact that Western society is not structured in a way that is in harmony with nature. Because of this, many individuals are unaware of the true purpose of the second half of life—to gradually release attachments and expand one's consciousness—and thus leave much of its potential unfulfilled.

The work of purification and detachment which should have begun in middle life is left until death overtakes them, and has therefore to be done upon the astral plane instead of the physical. Thus unnecessary delay is caused, and through his ignorance of the true meaning of life the man’s progress is slower than it should be. (Leadbeater, 1:71)

Although Leadbeater makes a valid point, it is also true that in Western society much help is available for the individual seeker. Modern depth psychology in particular provides valuable insights and strategies for navigating the shift in consciousness that occurs after midlife.

A good example is the theory of individuation developed by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung through an extensive study of dreams. From his perspective, the first part of life involves developing the persona, or the face we present to the world. The persona is composed of the individual personality traits with which we are comfortable: those encouraged by parents and teachers and sanctioned by society and our peer groups. The purpose of the later part of life is to rebalance oneself and become consciously attuned to the creative, unifying, ordering source of one’s being, which he called the Self.

Jung described, in great detail, the path of inner growth during the later years of life and the challenges that must be faced. In the first place, we must come to terms with the shadow: all those characteristics we have ignored or repressed because they are inconsistent with the persona, such as our fears, resentments, nonconformist ideas, and antisocial feelings. In the second place, we must integrate the anima (the female element within the man) or the animus (the male element within the woman). For a detailed discussion of the individuation process, see the chapter in Jung’s Man and His Symbols by Marie-Louise von Franz, a longtime associate of Jung.

Sometimes the shadow is not intrinsically negative, but is simply unacceptable to the conscious self. It can appear in dreams, usually as a person of the same sex as the dreamer, doing something that the dreamer would never consciously do.

One of my own dreams provides a good example of the shadow. I made a film of some event that took place in New York City. There was a stripper at this event, but I had left her out because she was too vulgar. Afterwards a man came to me and said that I should have included her. “She was an integral part of the whole thing.”

I realized that he was right. A film is a two-dimensional copy of a three-dimensional event. This may be a metaphor for the personality, which is a three-dimensional “copy” of a transcendent Self. So the dream is saying that my personality is not expressing something vitally important: the stripper, who defies the accepted mores of society with a flair. One message here is that I have been too proper, too accommodating, too concerned about the opinions of other people and with living up to their expectations. On another level, the process of synchronizing with the inner Self could be viewed as “stripping”: summoning the courage to remove worn-out ideas, unnecessary possessions, negative emotions, unhealthy relationships, and all other elements that can cover up our spiritual awareness. In The Cloud of Unknowing, one of the greatest works of Christian mysticism, the unknown author writes that we must put our personal attributes under a “cloud of forgetting” and make a “naked intent to God” (John-Julian, 21, 71).

Unfortunately, an unacknowledged shadow can be projected onto other people, thus interfering with our relationships. From Jung’s perspective, therefore, resolving interpersonal difficulties—which Leadbeater wrote was so important—involves first trying to rebalance ourselves.

The shadow, when unacknowledged, can also interfere with our creative work. In A Room of One’s Own, her classic book about women and fiction, Virginia Woolf wrote of the tendency for repressed anger and other unresolved personal issues to alter the clear vision of the writer and fragment her story: the author writes about herself when she should be writing about her characters. Woolf explained further that an “incandescent” mind—such as the mind of Shakespeare or Jane Austen—is one in which the darker, shadowy elements have been burned up and consumed. The light of creativity is thus undimmed and undistorted, and the works that come forth are complete in themselves.

Although it is unclear if Woolf (an avowed agnostic) was familiar with Jung’s work, she poetically described the other great challenge of the individuation process: the integration of the animus in the woman and the anima in the man. In the following passage from A Room of One’s Own, Woolf notes that when these elements come together, the individual is naturally creative and “incandescent.”

I went on amateurishly to sketch a plan of the soul, so that in each one of us two powers preside, one male, one female; and in the man’s brain the man predominates over the woman, and in the woman’s brain the woman predominates over the man . . . If one is a man, still the woman part of the brain must have effect; and a woman must also have intercourse with the man in her. Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. It is when this fusion takes place that the mind is fully fertilized and uses all its faculties . . . He meant, perhaps, that the androgynous mind is resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent, and undivided. (Woolf, 102)

The following dream from my journal illustrates the need for an integration of the male within the female. I was looking through a pile of Life magazines. A picture of Queen Elizabeth II, wearing her crown, was on the cover of every issue.

“This isn’t right,” I thought. “She shouldn’t be here all the time.”

Then I looked at some pictures of other people who deserved to be on the cover. Most of them were men: a fact that I found significant. I felt drawn to one of them. He had a strong, intelligent face; he might have been a sea captain or an explorer.

“He should be on the cover,” I thought.

I felt the dream was telling me that feminine qualities, symbolized by the long-reigning queen of England, had been ruling my consciousness for too many lifetimes. Now it was time for a change, time to rebalance by welcoming the sea captain into my life. I needed to express some masculine qualities: to become more assertive, even in a quiet way; to stop continually adjusting to the desires of others; to follow my own path; to be more willing to take risks. It is significant that in the previous dream about the shadow, it was a male figure who told me that the stripper should be integrated.

Von Franz wrote reassuringly that when a sincere effort is made to rebalance oneself and follow the path of individuation, one eventually accesses one’s organizing, creative center: “Whenever a human being genuinely turns to the inner world and tries to know himself . . . then sooner or later the Self emerges. The ego will then find an inner power that contains all the possibilities of renewal” (von Franz, 215).

In dreams the Self can emerge in many symbolic forms: as a superior human figure such as a wise old man or priestess or divine child; as a sacred or helpful animal; as a precious stone or crystal with its ordered configuration. In the following dream, the Self came to me in the form of a powerful lioness.

I was standing just inside a forest, looking out on an open field. A lioness appeared in the field. She saw me and immediately ran toward me. I thought that surely this would be the end of me. When she reached me, however, she stood behind me and enveloped me with her paws in the most benevolent manner. I had the impression that she thought I needed her. But because she was so tremendous, I didn’t feel completely at ease with her. I stood very still, hardly breathing.

Then the scene changed, and I was trying to tell a group of people about this extraordinary occurrence. They weren’t paying much attention to me.

From the metaphysical perspective described above, the clear field represents the unified level of intuitive wisdom, while the forest represents the level of the mind which is filled with details. I stood on the boundary between these two dimensions. The dream seems to be saying that help will come from the clear field of buddhi. It will be both powerful and protective, so I should not be afraid to follow the tide of consciousness as it flows on its inward journey. And there was a warning in the dream: conventional society would not appreciate that which was so significant to me.

The idea of creative insight as compensation, which the woman in the lecture hall experienced—a triumph of the human spirit over memory losses and other physical issues of aging— was beautifully expressed by Mildred Miller, my favorite early-twentieth-century artist. The following passage is from a diary she kept when she was codirector of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts Summer School, dated July 15, 1927:

Yesterday I was working on a hayfield, and when I painted the light on a man’s hat against the loaded wagon it seemed to me that I had struck the actual appearance. “Can it be possible,” I thot, [sic] “that I can really make my own the beautiful light that I see, that I can look at the light dripping from a horse’s flank and say “You are mine?” If I can do that I would not mind old age or being ugly, sickness or death. (Brown, 106)

Not all of us are artists like Mildred Miller, but we can all touch the inner source of creative renewal and—in our own unique ways —express it in the world.

Sources

Arnold, Edwin. The Song Celestial: A Poetic Version of the Bhagavad Gita. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1975 [1885].

Brown, Virginia. Mildred Miller Remembered. Xlibris, 2006.

Cook, Edward. The Life of Florence Nightingale. Two volumes. London: Macmillan, 1913.

Freeman, Philip, trans. How to Grow Old by Marcus Tullius Cicero. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Father John-Julian, trans. The Complete Cloud of Unknowing. Brewster, Mass.: Paraclete Press, 2015.

Leadbeater, Charles. The Other Side of Death Scientifically Examined and Carefully Described, Two volumes. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

Nicholson, Shirley. Ancient Wisdom, Modern Insight. Wheaton: Quest Books,1985.

Rohr, Richard. Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011.

Smith, Huston. The World’s Religions. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

Von Franz, Marie-Louise. “The Process of Individuation.” in Carl Jung et al., Man and His Symbols. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1964.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1929.

Janet Macrae taught holistic nursing for many years at New York University. She is the author of Nursing as a Spiritual Practice: A Contemporary Application of Florence Nightingale’s Views (Springer). Her article “Original Vision: On the Choice of a New Life” appeared in Quest, fall 2020.